The study of wine history is revealing, if we only had time for it. Today, most people are too busy trying to keep up with the pressures of high-tech life to appreciate the background and history of the wines they love best. To understand the origins of a wine is to better appreciate how it contributes to the pleasures of modern living.

Although the history of wine and its influence on civilization is fascinating, from ancient Egypt to the expansion of the New World, the story of the evolution of Port wine holds special interest. “Wonderful wines are harvested in the Douro, whence they are shipped to the city of Porto,” wrote the 16th century Portuguese historian Joao de Barros. Traveling from one end of the Douro to the other, Barros recorded his observations in his Geografia. Hundreds of years have passed since Barros' journey, yet the savage beauty of the Douro River valley has changed little. Douro wines, on the other hand, underwent more dramatic changes, spurred on by three significant events that caused the character of Douro wines to undergo a significant transformation.

wines are harvested in the Douro, whence they are shipped to the city of Porto,” wrote the 16th century Portuguese historian Joao de Barros. Traveling from one end of the Douro to the other, Barros recorded his observations in his Geografia. Hundreds of years have passed since Barros' journey, yet the savage beauty of the Douro River valley has changed little. Douro wines, on the other hand, underwent more dramatic changes, spurred on by three significant events that caused the character of Douro wines to undergo a significant transformation.

When the Douro region became an independent kingdom in the 12th century, the predecessor of what we know today as Port began production. In the early 16th century the Douro was producing the equivalent of 600,000 cases, increasing to 1.2 million cases of Port wine by the beginning of the 17th century. At the close of the 17th century, the first event that initiated a major change in the Douro the British discovery of Port wine, which soon spread its name throughout the world.

Because of political problems between France and England in the 1660s, Bordeaux, the preferred wine of the English nobility, became scarce. Merchants soon offered Port wines and were met with success in the English markets. Four years later, Warre became the first English Port firm to open business in Oporto. The name Port derives from Oporto, Portugal’s second largest city and the hub of the Port export trade for more than 300 years. By the mid-18th Century, America began importing Port wine, even though the signers of the Declaration of Independence toasted the historic event with a glass of Madeira, Portugal’s other great fortified wine.

The transformation of Port from a dry table wine to a sweet fortified wine was the next major event to change Douro wines forever. Despite apocryphal tales to the contrary, the transformation didn’t occur overnight but was gradual, especially since the usual practice of the day was to add brandy up to 3% of the total volume to preserve the wine during shipment. Then in 1820, an especially ripe vintage yielded very sweet wines and the rush was on for more of the same. Not every Port house favored the new style, but by the mid 19th century, Port as we know it today had captured the interest of the world’s wine drinkers.

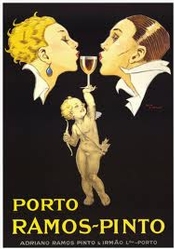

And that brings the story of the evolution of Port wine to the 20th century and the development of the third major event to change the character of the fortified wine. “When I came to Ramos Pinto in 1976, my uncle José Ramos Pinto asked me to study the different varieties of Port and select them for the new plantations,” recalls Joaõ Nicolau de  Almeida, CEO of Ramos Pinto and the person in charge of making all the wines. He notes that when he started his task there were many varieties in use. Now, says de Almeida, there are 80 different white and red varieties allowed, with 40 advised, to make Port wine. “At Ramos Pinot we use mainly Touriga Nacional, Touriga Francesa, Tinto Cao, Tinto Roriz, Tinto Barroca, Tinto da Barca and Souzao.

Almeida, CEO of Ramos Pinto and the person in charge of making all the wines. He notes that when he started his task there were many varieties in use. Now, says de Almeida, there are 80 different white and red varieties allowed, with 40 advised, to make Port wine. “At Ramos Pinot we use mainly Touriga Nacional, Touriga Francesa, Tinto Cao, Tinto Roriz, Tinto Barroca, Tinto da Barca and Souzao.

Those seven varieties are planted in four quintas (vineyards) owned by Ramos Pinto: Quinta do Bom Retiro, a magical place that nestles in a pocket valley above the Douro River; Quinta de Ervamoira, a remote site at the upper reaches of the Douro Valley with its almost perfect amphitheater-shaped vineyard bowl that looks out over the river; and Quinta da Urtiga and Quinta dos Bons Ares. Ramos Pinto grows all of its own grapes except for some white grapes used to make the white Port Lagrima.

Quinta de Ervamoira is in the Douro Superior, far inland where the Douro River meets with the Coa River. Ervamoira is an engaging spot of raw beauty with broad vistas and an unnerving but satisfying quiet that almost crackles. The 240 acres of what de Almeida calls “our experimental vineyard” are planted vertically to five main varieties. “At Ervamoira we started studying blends to better understand the different potential of each variety and the influence on fruit intensity, body and flavours,” explains de Almeida. “With the vinifications we tried to develop the alcoholic fermentation to produce a fruitier, fresher more aromatic wine.”

that almost crackles. The 240 acres of what de Almeida calls “our experimental vineyard” are planted vertically to five main varieties. “At Ervamoira we started studying blends to better understand the different potential of each variety and the influence on fruit intensity, body and flavours,” explains de Almeida. “With the vinifications we tried to develop the alcoholic fermentation to produce a fruitier, fresher more aromatic wine.”

Traditionally, vineyards planted on the steep river banks of the Douro were all on terraces, cut back into the slopes, often with enough space to accommodate two or three rows of vines. But horizontal terraces had some limitations, so when Ervamoira was planted the decision was to experiment with vertical planting. “In my view, vertical planting allows for a high density plantations with 5,000 plants per hectare (2.47 acres) compared to 3,000 vines on a terrace. Vertical plantings produce more per hectare and less per plant which means the vines are in competition and have to push their roots deeper, providing more nutrients,” says de Almeida. Further, he notes that vertical planting allows a higher degree of mechanization in the vineyard and there is less erosion.

To understand the uniqueness and charm of a place like Quinta do Bom Retiro, you have to go there. Bom Retiro, in the Cima-Corgo sub-region on the Douro River where it meets the Torto River, can be reached by train from Oporto, or by car winding along the Douro River, then a twisting road back to the quinta, situated in a shallow valley between a native forest reserve and groves of olive and almond trees. Sitting on the porch of the main house at Bom Retiro on a balmy evening, sipping a glass of tawny port and munching almonds, while listening to the distant sounds and watching lights twinkle at neighboring quintas is a rewarding experience that is hard to duplicate.

Quinta do Bom Retiro farms 120 acres of 25-year-old vines in a patchwork of different vineyard schemes, with pre-phylloxera vines planted horizontally in traditional wide rows on terraces sculpted from the steep hillsides buttressed with stone walls, to the more modern vineyard scheme of vertical plantings. The old vines at Bom Retiro contribute to Ramos Pinto vintage ports, but also to a selection of Tawny Ports, including the smooth, complex and layered Porto 20 Years Tawny and as a contributing component of the velvety, seductive Porto 30 Years Tawny. To avoid confusion, it is worth noting that labels on Port wines use the name “Porto” to refer to the wine, while most references outside Portugal prefer “Port.”

While the differences in physical locations, soils and sub-soil geology are striking between Quinta de Ervamoira and Quinta do Bom Retiro, the characteristics of the Porto wines made from these two quintas is equally impressive. “At Bom Retiro the wine flavours are very elegant, fresh and have more acidity than Ervamorira wines, although the concentration of colour and fruit depends a lot on the year,” explains de Almeida. “At Ervamoira the wines are softer with smooth tannins, less acid than the wines of Bom Retiro but with a great fruit concentration and a deep red colour.” Noting the difference in age of the two quintas, de Almeida adds: “The quality of Ervamoira gets more constant from one year to the other.” Porto wines from all Ramos Pinto quintas are  aged in oak barrels, previously used for four years to mature Douro still wines. “For Port we don’t need the tannins and flavors from the wood, but we do need the micro-oxigenation through the pores of the wood.”

aged in oak barrels, previously used for four years to mature Douro still wines. “For Port we don’t need the tannins and flavors from the wood, but we do need the micro-oxigenation through the pores of the wood.”

Besides the extensive line of Port wines, Ramos Pinto makes Duas Quintas, a Douro wine that combines select grapes from Quinta de Ervamoira and Quinta dos Bom Ares. Douro wines, the name used for still wines made in the Douro Valley, usually from the same grapes used to make Port wine, account for about 40% of the total production sold worldwide.

De Almeida believes that Port wine is one of the greatest wines in the world, for which he would get no disagreement from this writer. But he cautions: “Only the occidental part of the world knows it. We have to maintain the sales in this part (the West) and show the Port to the rest of the world.”

* * *

Questions or comments? Write me at gboyd@winereviewonline.com