There’s an old real estate saying about the value of owning the cheapest house in an expensive neighborhood. An analogous truth shows up in the world of winegrowing, one concerning not price but temperature: seek out the coolest sites in a warm growing area. It’s a premise that led the Catena family high into the Andes and the creation of what became their flagship site, the Adrianna Vineyard.

Named for Nicola Catena Zapata’s youngest daughter, the vineyard, situated in the Gualtallary sub-region of the Tupungato region (which in itself is part of the Uco Valley) lies at almost 5,000 feet in elevation. There are a few vineyards stretching a bit higher up into the Andes, but not many, and even then, only by a few hundred feet. Increased elevation moderates the heat in a couple of ways. Temperatures overall may be lower, in some cases decreasing by about one degree Fahrenheit for every 100 meters of elevation. But perhaps even more significantly diurnal variation – the up and down of daytime versus nighttime temperatures – is much greater. In the Adrianna vineyard day and night temperatures typically vary by more than 55 degrees Fahrenheit during the growing season. During the cool nights respiration continues within the vines, but without the “power plant” of photosynthesis. The vines must therefore rely on carbohydrate and nutrient reserves within the plant, including within the grape berries. The cooler temperatures slow respiration and the consumption of these reserves, resulting in greater concentration of color, flavor, and tannins in the grapes.

Extreme elevations also bring additional ultraviolet light; according to some research, the amount of UV striking the grape bunches goes up by 10-12% for every 1,000 feet of elevation. Anyone who’s gone mountain hiking at significant elevations has noticed how much more quickly their sunscreen failed them than usual. UV light has several effects on the grapes that then make their way into the wine. Typically, it results in thicker skins, more concentrated color, and riper, more complex tannins – stronger, but at the same less drying or harsh.

Catena’s exploration of higher elevations led to the planting of the Adrianna Vineyard in 1992, and it has since become the source of several of their most highly regarded wines. The topsoils are largely alluvial, deposited by water flow down the Andean slopes, and contain a mix of gravel and limestone; the latter extends deep into the subsoil. The western end of the vineyard is largely planted to Chardonnay, with red varieties, most notably Malbec and Cabernet Sauvignon, further east.

The combination of limestone and Chardonnay evokes Burgundy, but only one of the two Chardonnays Catena makes from Adrianna Vineyard nods to that style. The “White Bones” Chardonnay is planted on an old riverbed, with little topsoil. The 2018 is relatively lean and focused, with racy acidity. Pear and apricot notes supported a pronounced spicy floral nose, with a mint and lemongrass figuring prominently. By contrast the slightly smaller plot that yields the “White Stones” Chardonnay contains larger rocks, with slightly more topsoil. The 2018 is generous, extroverted, and ripe, and leans toward tropical pineapple aromas. It’s full and round, but still clean.

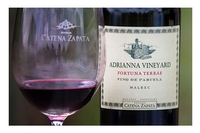

Further east the topsoils are deeper. The Fortuna Terrae Malbec comes a five hectare plot a few hundred feet lower than the Chardonnay vineyards. The 2017 shows black raspberry, blackberry, and pomegranate notes along with a touch of smokiness. It’s full-bodied, with soft, dense tannins that speak to the influence of UV light.

Catena makes two other Adrianna Vineyard Malbecs, one from a plot immediately to the north of the Fortuna Terrae block and one closer to the White Bones block, but I’d also note the true flagship wine, the Nicolas Catena Zapata, which blends Cabernet Sauvignon and Malbec from this vineyard with additional Malbec from the lower altitude Nicasia Cru in the Paraje Altamira subdistrict. This is a wine I took pleasure in showing off to customers when I was a sommelier, and one able to satisfy typical Malbec fans who are looking for big, generous, spicy wines as those who are more interested in structure and texture. The 2016 is round, full, and generous, but still firm, and shows a spicy, floral, blackberry that evolves and expands into a mix of black and blue fruits in the glass.

Catena calls the Adrianna Vineyard a “Grand Cru.” I’m generally skeptical of the value of applying these sorts of classification terms outside of their registered uses in places like Alsace, Bordeaux, or Burgundy. At best, it seems like these terms are what the animator Chuck Jones called “gift words.” The example he gave was the word “poet:” someone might say they write poems, but it is for someone else to say they are a poet and grant them that title. Conditioned as I am by Burgundy and Alsace, I’m also inclined to think we should see how a vineyard performs in the hands of multiple wineries before it earns a title like Grand Cru, but there’s no real logic behind that presumption. Given how different the business and history of Mendoza is from those French regions, why shouldn’t a Grand Cru be a monopole? And therefore, why shouldn’t Adrianna Vineyard deserve the title of Grand Cru?

Photos Courtesy of Catena Zapata www.CatenaZapata.com