|

|

|

If you’re an oyster enthusiast as well as a wine lover I’m sure you’ll agree with me that one of the best things about our favorite bivalves is how much they can enhance the pleasure of imbibing a glass of Muscadet, Sauvignon Blanc, Chablis or Champagne. But oysters have an even more important role to play than bringing us gustatory happiness: As dynamo filters, we are counting on them to help clean our polluted water systems.

When the explorer Henry Hudson sailed his 85 foot ship the Half Moon into the New York Harbor in 1609, he had to navigate around 220,000 acres (acres!) of oyster reefs. The oysters in the harbor had sustained the local Lenape people for generations, and when Hudson arrived that estuary was one of the most biologically pristine, diverse and dynamic waterways in the world.

Fast forward to 1906. Not a single oyster is left in New York Harbor, having all disappeared down the gullets of rapacious New Yorkers. The oyster reefs have been dredged up or covered by silt, and the water is hopelessly polluted by chemical waste and oil residues. In fact, the water quality is too poor to sustain any kind of marine life, not just in New York but in harbors, bays and estuaries up and down the east coast of the United States.

Fifty years later, with the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1977 and other environmental laws that prohibit the dumping of waste and raw sewage into the harbor the tide begins to turn. Today, at the dawn of the 21st century, water quality has improved enough for large-scale oyster restoration projects to move forward.

The Chesapeake Bay Project, for example, a venture on Maryland’s Eastern Shore led by the Nature Conservancy in partnership with NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association) is said to be the largest oyster restoration project in the world, having established an oyster reef covering 350 acres that was recently seeded with 2 billion oysters. These bivalves were bred at a University of Maryland Hatchery to be resistant to various diseases that, along with overfishing and pollution, have been decimating the oysters.

Since oysters help clean the Chesapeake of pollution, scientists believe this enormous reef might play a role in reducing the nitrogen that chokes marine life when it flows into the Bay as fertilizer.

The Massachusetts Oyster Project is an all-volunteer organization dedicated to the restoration of oysters to the state’s marine estuaries, starting in the Boston area.

The Billion Oyster Project, an ecosystem restoration and education project, has engaged hundreds of thousands of school children in a program designed to restore one billion live oysters to New York Harbor. In the process of working with BOP to restore the ecology and economy of their local marine environment, kids at New York Harbor School are acquiring a host of new skills including learning to SCUBA dive, raising oyster larvae, and designing and operating underwater monitoring equipment.

Oysters produced in hatcheries thrive best if they can find shells to attach to when they are released into the bay, but because of the diminished oyster population shells along the Atlantic coast are scarce. Providing shells for the spat to cling to has therefore become a vital component of oyster restoration, with several states along the nation’s shoreline instituting Oyster Shell Restoration Programs, whose mission is to return shells to the water via public shell drop-off sites and shell recycling programs that enlist restaurants, caterers and food distributers to collect and donate their used shells.

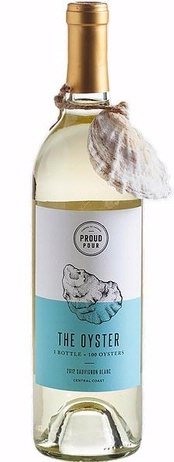

But by now you are wondering what you can do to help save the oysters, right? The answer is simple: drink more wine! Specifically, drink “The Oyster,” a Sauvignon Blanc produced by Proud Pour, a fledgling brand dedicated to helping restore oysters to local habitats.

Proud Pour’s ultimate goal, said Brian Thurber, the company’s co-CEO, is to  help solve environmental problems through wine sales. “Our first wine is ‘The Oyster.’ For every bottle of the wine purchased we fund the restoration of 100 wild oysters by a local partner restoration project. We sell only in markets where we can connect the consumer to local oyster restoration work. We’re currently selling in New York, supporting the Billion Oyster Project Massachusetts, and in Massachusetts with the Massachusetts Oyster Project.” help solve environmental problems through wine sales. “Our first wine is ‘The Oyster.’ For every bottle of the wine purchased we fund the restoration of 100 wild oysters by a local partner restoration project. We sell only in markets where we can connect the consumer to local oyster restoration work. We’re currently selling in New York, supporting the Billion Oyster Project Massachusetts, and in Massachusetts with the Massachusetts Oyster Project.”

“The idea is not just to provide funding for these projects, but also to raise awareness about them,” Brian added. “We have a different label in each state to highlight the great local work that is happening. Eventually we plan to support oyster restoration up and down the east and west coasts. Our long term vision is to restore various critical species and ecosystems with different wines.”

I’m anxious to see what’s next from Proud Pour. A Pinot Gris to raise awareness of the endangered gray whale, perhaps? An unoaked Chardonnay to help solve the world’s deforestation problems? Pinot Noir to save the critically endangered black Rhino? While we’re waiting, let’s get those oysters shucked and a bottle of Proud Pour Sauvignon Blanc opened to enjoy with them.

Proud Pour Sauvignon Blanc $23: An immensely likeable white wine made in a sunny, fruity style rather than the tangy, high acid model often associated with Sauvignon Blanc. Light-to-medium bodied, it can certainly stand alone as an aperitif tipple, but like all the best wines the real pleasure comes when it is enjoyed with food--in this case shellfish or even light pasta dishes make perfect partners for Proud Pour’s Sauvignon Blanc.

|

|

|