|

|

|

|

January 15, 2013

Creators Syndicate

My recent column on "American Wine," the book (by Master of Wine Jancis

Robinson and American wine journalist Linda Murphy) as well as the topic, struck

a chord last week with one reader. John Bojanowski is a native of Kentucky who

now lives in the south of France, making wine at Clos du Gravillas in St. Jean

de Minervois.

Wrote John:

"I'm delighted to see this book, as I respect what Jancis

writes and am personally interested in the subject. I grew up in Kentucky and

somehow ended up growing organic grapes and making wines (out of unloved

varietals, most passionately) in St Jean de Minervois, Languedoc. "I'm delighted to see this book, as I respect what Jancis

writes and am personally interested in the subject. I grew up in Kentucky and

somehow ended up growing organic grapes and making wines (out of unloved

varietals, most passionately) in St Jean de Minervois, Languedoc.

"I'm back home in Kentucky a couple of times per year and have noted two

things: The number of Kentucky wineries has gone from 5 to 50 in 10 years, and

each time I go back, I buy four to five bottles, which inevitably finish in the

sink.

"A firm believer that it is possible to make good wine 'in most places

and with most varietals,' I look at Kentucky's advantages (limestone) and think

there might be application there for some of what I've learned over here in

France (it don't get no more limestonier than in St. Jean de Minervois ...). I

think there's a philosophical muddle going on — the neo-growers are trying to

'make to market' rather than discovering 'good practice' to figure out how to

make good taste under local conditions (and local good practice is much easier

to find here than in Kentucky).

"Ever had a good Kentucky wine or even a drinkable one? I visited Jim Law

at Linden in Virginia a few years ago, and he's understood his vineyard

constraints absolutely. So I know Kentucky is possible."

I know next to nothing about Kentucky wine, but I would say

to John that the growth spurt in the number of wineries over the past decade is

encouraging. That would seem to indicate that there is an underlying belief in

the potential of the region. I know next to nothing about Kentucky wine, but I would say

to John that the growth spurt in the number of wineries over the past decade is

encouraging. That would seem to indicate that there is an underlying belief in

the potential of the region.

There are many challenges in these non-traditional winegrowing regions, which

is why so many aspiring vintners locate in California, where the conditions are

just about ideal.

For example, Eastern wine regions such as Pennsylvania, New York, North

Carolina, Virginia and Georgia often have a wet spring. That happens in

California, but not very often.

Those areas also are prone to hail in the summer months, which is rare in

California. Then there is the shorter growing season, which makes it tricky as

harvest (and stormy weather) approaches as the leaves begin to turn.

Yet in recent years we've seen glorious wines emerge, crafted by

dedicated vintners who've figured out the climate and the soil and made the

advances in technology and vineyard practices that were necessary to produce

high-quality grapes. Perhaps Kentucky will be next, although to this point none

of the wineries there have mustered the courage to compete on the world wine

competition stage — at least, not that I am aware. Yet in recent years we've seen glorious wines emerge, crafted by

dedicated vintners who've figured out the climate and the soil and made the

advances in technology and vineyard practices that were necessary to produce

high-quality grapes. Perhaps Kentucky will be next, although to this point none

of the wineries there have mustered the courage to compete on the world wine

competition stage — at least, not that I am aware.

But I have no doubt that if there's good wine being made in Georgia and Ohio

and Michigan and Missouri and South Dakota and Colorado — and there is — then

there's hope for Kentucky, too.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 1:02 PM

|

|

January 9, 2013

Creators Syndicate

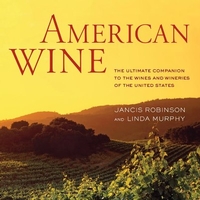

American Wine, a comprehensive look at the history and state of wine in

America co-authored by Master of Wine Jancis Robinson and Wine Review Online columnist Linda

Murphy, is scheduled to be released February 1. It is available on pre-order now

($45) at Amazon. It should be an eye-opener.

Although the focus promises

to be on the most important wine-growing regions in the nation, i.e.,

California, Washington and Oregon, the most important detail is the revelation

that good wine is made throughout America, often in places the average American

would consider improbable turf for winemaking.

The subject is

near and dear, for I have become a convert to the exciting viticultural

possibilities in, say, South Dakota. I won’t pretend that it is a budding Napa

Valley waiting to be discovered, but I do know there is a winery, Prairie Berry

in Hill City, SD., that has consistently racked up awards at the San Diego

International Wine Competition. The subject is

near and dear, for I have become a convert to the exciting viticultural

possibilities in, say, South Dakota. I won’t pretend that it is a budding Napa

Valley waiting to be discovered, but I do know there is a winery, Prairie Berry

in Hill City, SD., that has consistently racked up awards at the San Diego

International Wine Competition.

The wines of Prairie Berry are made from

grapes, such as Frontenac Gris and Vidal Blanc, that may not be familiar to the

average person, but at Prairie Berry they are transformed into delicious,

well-balanced wines that impress even grizzled wine judges with more experience,

and perhaps a small bias, toward more traditional grape varieties.

Even

more startling than the recent success of Prairie Berry was the accomplishment

last year of a winery from Wisconsin, Wollersheim, which racked up four platinum

awards and was named Winery of the Year at the San Diego International.

Wollersheim is located in Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin, where it, too, features

hybrid grape varieties made in a range of styles from dry to sweet, but with an

emphasis always on exquisite balance.

Less surprising but equally obscure

for most Americans are the superb wines of New York, where the primary growing

regions are the Finger Lakes upstate and the eastern end of Long Island. The

Finger Lakes specialize in aromatic whites, such as Riesling, Gewurztraminer and

Gruner Veltliner, while Long Island is a friendly environ for Cabernet Franc and

Merlot, with a smattering of good Riesling and Chardonnay.

I’ve also

tasted award-winning wines from neighboring New Jersey, Rhode Island and

Pennsylvania.

Further south, Virgina, North Carolina and Georgia have

made tremendous strides with more traditional grapes. I’ve grown fond of the

Cabernet Franc and Viognier from Barboursville and Jefferson Vineyards, both

near Charlottesville, Va., at the southwestern tip of the state. Barboursville

also makes what I consider one of the two finest Nebbiolo wines (this is the

grape of Barolo and Barbaresco in northern Italy) in North America (Baja,

Mexico’s LA Cetto makes the other) and Jefferson’s Chardonnay and Bordeaux blend

are perhaps the best made in the East Coast and always competitive when up

against California rivals in major wine competitions.

Georgia

has a small but significant wine-growing region in the mountains in the

southwest corner of the state, where the climate is hot and dry by day and

somewhat cool at night. Frogtown Cellars, located in Georgia’s Lumpkin County,

concentrates on elegant reds and lush whites made from traditional French grape

varieties. These wines also compete successfully on the world stage, always

winning a fair share of medals when entered in competitions that attract entries

from California, Washington, Oregon, Europe and the Southern

Hemisphere. Georgia

has a small but significant wine-growing region in the mountains in the

southwest corner of the state, where the climate is hot and dry by day and

somewhat cool at night. Frogtown Cellars, located in Georgia’s Lumpkin County,

concentrates on elegant reds and lush whites made from traditional French grape

varieties. These wines also compete successfully on the world stage, always

winning a fair share of medals when entered in competitions that attract entries

from California, Washington, Oregon, Europe and the Southern

Hemisphere.

I’ve also tasted award-winning wines in recent years from

Texas and Colorado.

The reason you may not be aware of this booming

culture of American wine is that California, for the most part, gets all the

glory. Washington and Oregon pick up California’s crumbs on the publicity front,

and the rest of the country goes begging for attention.

Hopefully

“American Wine” will alter that dynamic. I am reminded of a query from a San

Diego restaurateur just last week, wanting to know of any California

distributors who might have inventory from New York or Virginia. Sadly, I know

of none.

Even in New York City it is sometimes difficult to find a New

York wine, and my experience says the same is true of Virginia wines in Virginia

and Georgia wines in Georgia.

Perhaps you will read “American Wine” and

seek out some of the more interesting wines from unusual places. More than

likely you will be thwarted by your favorite wine merchant, but the internet has

changed the rules. Now you can hop on the computer and join a winery’s wine

club, bypassing the gatekeepers who either don’t know there are exceptional

wines made all over this country, or have little interest beyond the easy sell

of California wine.

There are amazing wines being made across America. A

book that documents the breadth of America’s winegrowing chops is long

overdue.

Email comments to [email protected].

Follow Robert Whitley on Twitter @wineguru or @WhitleyOnWine.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 7:47 PM

|

|

January 2, 2013

As we begin a new year there seems to be a growing obsession with the state of wine journalism. The shrinking of print media over the past few years has certainly altered the landscape, and the rise of the wine blogger has somewhat reshaped it.

Then there was the Natalie MacLean (popular in Canada, not so well known in the U.S.) kerfluffle over the use of reviews written by colleagues that were posted on her personal website, without their permission and often with vague attribution.

And finally there was the interminable navel gazing over the meaning and impact of famed wine critic Robert Parker's decision to sell an interest in his newsletter, The Wine Advocate, to investors from Singapore.

What we seem to have lost sight of is the purpose of wine journalism, which is to inform the public. Some journalists accomplish this through the telling of a good story, what my good friend Bruce Schoenfeld would call the "narrative." Others choose to analyze and critique, the purpose being to steer folks to good wines. Still others do both.

Parker was unique among us because he came along at a time, in the early 1980s, when the mission was not being served very well. He filled a void, and the so-called "trade" embraced him and his 100-point rating scale, which quantified his degree of approval for the wines he reviewed.

The Wine Spectator came on the scene at about the same time, but its focus seemed to be on California (if memory serves) while Parker's strength was Bordeaux, which had emerged as the world's most coveted of collectible wines, in no small way propelled by Parker's exuberance over the remarkable 1982 vintage.

So Robert Parker was the right man in the right place at the right time.

His 100-point scale (introduced I believe at about the same time The Wine Spectator went to the scoring system) has become controversial over the years, a backlash perhaps to the reluctance of many consumers to accept wines that fail to fetch a score in the 90s.

That's too bad because I find it useful and I believe it serves the public interest. When I first started to review wines in 1991 at the San Diego Union-Tribune, I chose not to rate wines with a numerical score. I changed my mind after becoming convinced readers really did want to know which one of those three recommended Cabernets I liked best.

I have read much recently about the demise of the wine writer and the death of the 100-point scale. I don't think either is in the offing. Indeed, there are more people writing about wine now than at any time since I entered journalism some decades ago. As for the 100-point scale, I still think most people get it.

Here at Wine Review Online, we will continue to strive to do the things wine journalists should do. That means we will tell you the story behind the wine, we will tell you about the wine, and we will tell you how much we like the wines we are writing about.

I firmly believe there is an audience for what we do. Every year for the past several years, WRO has recorded about a million annual visitors. We don't take their loyalty lightly. Our goal is to inform our readers and hopefully guide them to wines that are worthy of attention.

It's not rocket science. I've tasted this wine, I liked it. Maybe you will, too. It's no more complicated than that.

Posted by Robert Whitley at 4:44 PM

|

|

|

|