|

|

|

|

June 25, 2023

The first wine I ever tasted came in a paper bag. A neighbor in a pickup truck was driving up the rutted dirt road where both our families lived, and I was walking in the other direction. He stopped his truck, leaned out the window, and asked if I would like a “swig of wine.”

Even though I was not quite a teenager, it was neighborly of him to want to share, and, besides, perhaps he was tired of drinking alone. When you’re a young kid in rural Appalachia in the 1950s, such experiences outside the ordinary came very infrequently and were to be seized.

I said, “Sure,” he gave me a mystery bottle wrapped in the brown paper with only its neck exposed, and the rest is history. I did not see the label, and I did not take notes. That would come later.

Now, here it is 2023. I have yet to drink wine or – as would probably be the case – pour wine from an actual  paper bottle. But I expect that will come soon. paper bottle. But I expect that will come soon.

Shannon Valladarez also hopes so. Valladarez is an executive with the Monterey Wine Company at its King City facility in the Salinas Valley, and Monterey has signed an agreement with England’s Frugalpac to become the first contract winemaking producer to use the Frugalpac’s plastic wine and spirits bottles in the U.S.

“We will put in a new bottling line to handle the bottles without crushing them, which is quite difficult technically,” Valladarez says. “We are quite excited about it.” The Frugal bottles, as they are called, are made of 94% recycled paperboard wrapped around a food-grade pouch that contains the wine. The main advantage – which anyone who has wrestled with cases of wine in a retail shop or in a winery can attest – is a much lighter bottle. At only 3 ounces unfilled, it is several times lighter than glass bottles, especially those “serious wine” statement bottles.

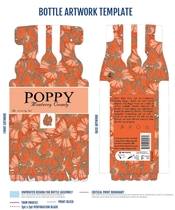

There is also a marketing advantage to the Frugal bottle, as the entire outer part of the bottle is a customized, one-piece, wrap-around label that lends all sorts of design possibilities. “Producers will give their whole design concept to Frugalpac, which will then produce and ship the bottles,” Valladarez says. “They have the option of asking themselves, ‘Do we go crazy or traditional with design?’”

All very good so far, except that to use the Monterey plant, producers will have to have their wine made at the custom crush facility or have the finished wine made at their own wineries and then shipped to King City for final  bottling. According to Frugalpac, traditional bottling lines cannot at present be easily adapted to handle the Frugal bottle, although that may come in time. According to a Frugalpac representative, only the Bordeaux-bottle shape is available, and the only closure available is screw cap. bottling. According to Frugalpac, traditional bottling lines cannot at present be easily adapted to handle the Frugal bottle, although that may come in time. According to a Frugalpac representative, only the Bordeaux-bottle shape is available, and the only closure available is screw cap.

As it now stands, the first filled Frugal bottles coming out of the Monterey bottling plant may contain that company’s own proprietary brand, Poppy.

For those who get off on the mathematics of carbon footprinting and other sustainability metrics, the Frugal bottle is a field day of figuring out just how good it is environmentally and how it will itself be recycled.

Frugalpac sent me some sample bottles to get an idea of their look and feel, but, alas, there was no wine in them. (I understand why, of course, but it is a bit like allowing an automotive editor to hop into the latest Porsche with no engine installed.)

So how do I feel about this development? Although I love the traditional glass bottle and cork – which will undoubtedly still be the primary way that wine is packaged and sold long after I’ve been cremated – I also can adapt to changes. Having myself graduated over the years from a portable typewriter to an IBM Selectric to a word processor to a Dell PC, I can’t pontificate too much against the onrush of technology.

But I do wish my long-ago neighbor, George, who died in the 1980s, were still living so that he could take a swig of wine with me from a paper bottle. Although George, in the ethos of hill culture, would still want to conceal it in a brown paper bag.

Posted by Roger Morris at 10:56 AM

|

|

June 7, 2023

Temperature is a crucial

factor in wine appreciation, yet it is a factor that is insufficiently

appreciated by many consumers. Wine critics and competition judges know

that any wine will taste dramatically different when tasted at different

temperatures. Similarly, sommeliers and connoisseurs know that the season

or even the ambient temperature in a room will affect the appeal of almost any

wine--whether advantageously or adversely. Being thoroughly informed

about the importance of temperature is one of the most helpful ways to pick

better wines and get the most out of them, usually without spending a dime.

I happen to live in Washington, D.C., where we are entering the blast furnace

of June-July-August. Seasonal suffering is a given, so the only questions

are these: Will your wine suffer also? And will you suffer while

drinking less-than-optimal wine?

Here are my four top tips for getting the most out of your wine when things

turn hot:

1) Chill ‘em Down:

Summer temperatures change the rules for proper serving temperature for wines,

both white and red, and getting the temperature right is an easy way to improve

any wine under summer conditions.

For most of the year, whites really aren’t at their best when pulled directly

from a refrigerator or an ice bucket. Extreme cold blunts their aromas,

sharpens their acidity and shortens their aftertaste. However, if you’re

going to have a glass of wine on a hot evening, it is worth remembering that

the ambient temperature will quickly warm the beverage in your glass.

If you will be enjoying a glass of wine for, say, 12 minutes from start to

finish, the point at which the temperature should be perfect would be the sixth

minute--not the first. If you or a friend find the wine too cold when it is

first served, the situation can be remedied by cupping it in one’s hand for 20

seconds. By contrast, it is much more difficult to deal with a glass that

goes warm once it has been served.

Where reds are concerned, you’d be well advised to ditch the conventional

wisdom that red wines should be served at room temperature. This made

good sense when the rule was established, which was probably in the 19th

century by some guy in an English manor house without central heat. The

room temperature in question was probably 62 rather than 72 degrees, and on a

hot day you’ll find that reds are dramatically improved when served at that

lower number.

Reds that are too warm will show too much alcoholic “heat” in their aromas and

aftertaste, and will seem soupy and unfocused, with insufficient acidity and

almost no refreshment value. When the weather gets really hot, I chill

every red that I taste (whether for review or for fun) into the refrigerator

for 20 to 30 minutes before opening.

Your guests may think this is strange, but the results are so convincing that

you won’t even need to offer an explanation. If you’ll be having friends

over for dinner during the next couple of months, and will thus have reason to

open two bottles of the same red wine over the course of the evening, chill one

of them for 20 minutes to half an hour, while leaving the second at room

temperature. I’ll bet that the results will change how you deal with red

wine forever.

2) Please Pass the

Acid:

One of the weirder aspects of “winespeak” is the talk about “acid” and

“acidity.” When growing up and being taught lessons such as don’t touch a

hot stove, the first thing we learn about acid is: Keep it out of your

mouth. Nevertheless, that is a lesson we’ve got to unlearn to appreciate

wine in adulthood, especially in a hot season.

Certain types of acids are indeed harmful, but the fact is that other types

(especially tartaric, malic and citric acids) are natural, beneficial

components in grapes and other fruits. All refreshing drinks enjoyed by

humans contain acidity, which is a vital component that works in relation to

sweet and bitter elements to produce pleasing taste sensations.

Although excessively acidic wines can seem unpleasantly tart or sour, wines

lacking sufficient acidity will strike almost everyone as flat, unfocused, and

“flabby.” As temperatures rise, we naturally crave drinks with more

acidity, as evidenced by the somewhat seasonal popularity of lemonade and

lemon-spritzed iced tea, which are appealing specifically because of their high

content of citric acid. Similarly, those wines that we particularly value

for refreshment (e.g., Pinot Grigio, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling) we value

precisely on account of their unusually high levels of acidity. It is

also worth noting that almost all sparkling wines are quite high in acidity,

since this is required to carry the flavors through the effervescence.

In practical terms, the importance of acidity connects to the two points that

precede and follow this one. First, remember that acidity is more evident

in solutions that are colder, so chilling wines thoroughly is not only a good

idea in its own right as a way to deal with hot conditions, but also crucial as

a way to accentuate the specific element in wine that refreshes us. Second,

wines vary in their acidity based on the climates in which the grapes are

grown. Cooler regions ripen grapes more modestly, producing less

sweetness but more acidity. So, as the following point will emphasize,

the smart money deals with hot weather with wines from cool locations.

3) Cooling Wines Come

from Cool Climates:

This point is not based on subjective interpretation but rather on hard facts

of biology and chemistry. As a wine grape (or any other fruit) ripens,

sugar increases and acidity decreases. (If you buy five nectarines and

taste one each day in succession, you can taste this process at work.)

Ripening is accelerated in hot climates, and slowed in cool ones. A hot

climate delivers a double whammy to the refreshment value of the wines made in

it, first by reducing the acidity that offers direct refreshment, and second by

driving up sugars. When sugars are fermented, they result in higher

alcohol and greater richness in the finished wine, both of which work contrary

to the objective of refreshment.

An interesting twist is that acidity is not a straightforward function of

daytime heat in a winegrowing region. It is, rather, a more complex

result of a region’s “diurnal range,” meaning the swings in temperature between

day and night. Unremittingly hot weather will literally decompose the

acids in a wine grape, but the effects of a hot day can be remedied by cool

nights, which preserve acidity. Thus it is possible to produce refreshing

wines from seriously hot places, provided that they also have particularly cool

nights.

High altitude locations fit this bill particularly well. One dramatic

example is provided by Rueda, which makes very crisp wines from the Verdejo

grape in central Spain. Even more dramatic is the example of Etna in Sicily,

where amazingly fresh whites and reds are made at a southerly latitude on a

smoldering volcano--thanks to the lofty elevation of the best vineyard

sites. These are two places that often see swings of 30 or more degrees

between temperature extremes within a single day.

Another twist is that climate seems to trump “varietal character” when it comes

to the refreshment value of wines. Although it is true that certain grape

varieties tend to be a bit leaner and more refreshing by nature than others, these

profiles are not “absolutes.” For example, most Chardonnays from

California or Australia are big, rich and creamy rather than lean, linear and

zesty. However, Chardonnay from a particularly cool climate like Chablis

in northern Burgundy is among the world’s most refreshing wines.

Finally, it is worth noting that “varietal character” is not absolute because

can be affected by decisions made by wine producer.

In the vineyard, decisions on when to pick the grapes can be vital in

determining the acidity levels and hence refreshment value of the resulting

wines. A telling case in point is provided by Pinot Grigio, which is

crisp and refreshing precisely because producers in northern Italy pick it very

early, before sugars rise and acids fall. Conversely, the same grape is

treated in the opposite manner when making most renditions of Pinot Gris in

Alsace, where late picking results in soft, sweet, low-acid wines.

In the winery, a winemaker need not simply play the cards dealt by nature if he

or she is working in a region in which wine production laws permit the

artificial enhancement of acidity. In most cases, these are regions that

have hot, sunny climates in which low acidity is a chronic challenge.

Thus, laws in California and Australia permit the “adjustment” of acidity

levels by the addition of tartaric acidity, and winemakers routinely avail

themselves of this option.

If skillfully performed, these adjustments may not be apparent in the finished

wines. However, no winemaker would prefer to adjust acidity levels

artificially if it were possible to work with grapes that are naturally

balanced. This is why acidification is prohibited in most European

regions, which can usually get all the acidity they need. However, the

flip side of this coin is that most of these same European regions struggle

with the opposite challenge of attaining optimal ripeness, and hence these

regions may permit additions of sugar--a practice forbidden in California and

Australia.

4) Certain Grapes

Enhance Your Odds:

I hesitate to add suggestions about grape varieties because I believe that the

whole concept of “varietal character” is a bogus notion.

Defending this stance fully would require an entire column, but the basic idea

is easy to convey. Chardonnay, for example, does not have a particular

profile, but rather a range of possible profiles resulting from where it is

grown and how it is vinified. A rendition grown in Australia’s Hunter

Valley and fermented in new oak barrels will be hugely different from one grown

in Chablis and vinified in stainless steel tanks.

Moreover, the differences are directly pertinent to temperature

considerations: Chablis is a great wine for a hot night, and a thick,

oaky Chardonnay from the Hunter is, in my opinion, just about as bad a choice

as one could make. Likewise, a Sauvignon Blanc from Marlborough in New

Zealand will probably be terrific in this situation, whereas a barrel fermented

rendition from California will be nowhere near as refreshing.

So why am I including this fourth suggestion at all? Basically, because

it remains true that different grape varieties are more or less likely to

produce refreshing wines, even though exceptions abound.

In my view, the climate of the growing region and the techniques employed by

the winemaker are both more salient than the grape variety used to make a

wine. However, casual consumer can’t be expected to know the climate

profile of all the world’s growing regions, and most wine labels don’t disclose

production techniques. Therefore, a list of which grapes are most likely

-- other factors being equal -- to produce refreshing wines will probably do

more good than harm. So, I’ll close by listing my top candidates, in

alphabetical order:

White: Albariño, Arneis, Assyrtiko, Carricante, Cortese, Falanghina,

Fiano, Godello, Greco, Grüner Veltliner, Moschofilero, Pinot Grigio, Piquepoul,

Ribolla Gialla, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Sylvaner, Torrontes, Verdejo, and

Verdicchio.

Red: Agiorgitiko, Barbera, Cabernet Franc, Corvina, Dolcetto, Gamay,

Grenache, Lagrein, Lemberger (a.k.a. Blaufrankisch), Mencía, Pinot Noir,

Sangiovese, and Tempranillo.

Posted by Michael Franz at 4:46 PM

|

|

|

|