In the first chapter of “Wines of the New South Africa,” author Tim James sets a reflective but promising tone by explaining that “…a significant portion of the best South African wines today were not being made in 2000, and many of what are now recognized as the finest wineries were not yet established.” James, a Cape Wine Master and freelance wine journalist, is  echoing the words of John Platter, the dean of South African wine writers, who prophetically wrote in his 1996 “South African Wine Guide: “Often, the Cape’s youngest wines are its best. And the finest have not yet been bottled.”

echoing the words of John Platter, the dean of South African wine writers, who prophetically wrote in his 1996 “South African Wine Guide: “Often, the Cape’s youngest wines are its best. And the finest have not yet been bottled.”

During the stifling period of Apartheid, South African viticulture and winemaking suffered. But following the repeal of Apartheid in 1990 and throughout the decade of the 1990s, the Cape wine industry moved forward steadily as trade and exchange of intellectual information increased. Under Apartheid–and the international sanctions that were raised in response to it–international trade and travel had slowed to a trickle, and the wine industry fell behind, not benefiting from the advances in viticulture and enology, enjoyed by the rest of the wine world.

The re-launch of the South African wine industry into the international market was triggered by an historic event that is still talked about today. In 1990, Apartheid was abolished and Nelson Mandela was released from more than 25 years of imprisonment. This momentous change opened South African society and re-inserted the country’s place in international trade. South African grape growers and winemakers began to travel and exchange ideas and learn of new technology that would help bring their wines up to a competitive world level. In many ways, it could be said that in 1994, when Nelson Mandela was elected President, the South African wine industry was re-born.

Thus, “Wines of the New South Africa” is not so much a story of the history of wine in South Africa as it is a contemporary look at the progress of the Cape wine industry since the mid 1990s. James writes passionately and intelligently about the wines of his homeland, stressing that the individual wines winning acclaim today are from a very young industry.

Therein lies the main problem with this book for American wine drinkers. Many of the small South African wineries touted by James are mostly unknown today in the United States, or are available only in select markets. When I first went to South Africa, after the fall of Apartheid in the early 1990s, there were only two or three small U.S. companies importing South African wines. Then, you could ask any American wine buyer to name a South African wine brand and the one or two likely to be mentioned was Stellenbosch Farmers’ Winery or the huge cooperative, KWV. In the 13 years since, the import picture has improved, but by and large, South African wines are still not common in many U.S. markets.

Nevertheless, wine lovers of every stripe should find “New South Africa” interesting reading. James sets the stage in the first four chapters with the basics of all wine text/references: History, grape varieties and wine styles, legislation, labels and terroir. For many wine collectors, the section, “The KWV Years: South African Wine to 1994,” will have the most meaning since it reflects the beginning of the “new” wine industry. Wine drinkers with a passion for regulations and appellations, will enjoy Chapter 4, “Wine of Origin.” This short chapter addresses The Wine of Origin appellation system of 1973 and how it differs from European and non-European systems. As James points out, “Like other non-European systems it (WO) does not seek to control aspects such as grape varieties, yields and planting densities on an appellation basis.” The U.S. AVA system, established much later than the WO system, is similar in what it proscribes and controls.

The bulk of the book, chapters 5 through 12, covers South Africa’s two dozen wine regions. But unless you are a South Africa wine specialist, the chapters on Stellenbosch, Paarl and Franschhoek (6, 7, 8) are the most informative on the appellations for the majority of South African wines available in the United States. The format is identical for all regional chapters: Background, Wards, and Wineries. In South Africa, a ward is a geopolitical subdivision of a city or town.

Stellenbosch, arguably the most important wine region in South Africa, is given a full 67 pages in the wineries section, a strong statement by James of the status of this storied wine region. Scattered among the many recommended winery mini-profiles are these familiar names: Kanonkop, Ernie Els, Neil Ellis, Fleur du Cap, Ken Forrester, Meerlust, Mulderbosch, Rust en Verde and Warwick. Gary and Kathy Jordan’s eponymous winery is marketed in the United States as Jardin, to avoid conflict with Sonoma’s Jordan Vineyard.

Glen Carlou, a South African winery known to many American wine consumers, since it is owned by the Swiss-based Hess Group, which also owns Napa’s Hess Collection, is mostly dismissed by James as having “evolved in a notably ‘commercial’ direction.” Stating that the Glen Carlou Chardonnay was “one of the Cape’s best examples in the 1990s,” the wine apparently slid down the slippery California slope after the arrival of Donald Hess. The Chardonnay “became less characterful (sic) and serious, with a particular California type as a model,” notes James.

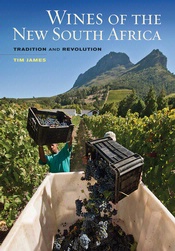

Wines of the New South Africa is a textbook in the truest sense, as there are no photographs and just 13 basic maps that offer little detail. Apparently, the aim behind the maps is to give the reader a general location of each winery mentioned by James, but not provide the individual region’s proximity to other neighboring regions.

Considering the $40 cover price, one must regret that this book–like other recent releases from University of California Press–lacks photos and offers only very basic maps. Still, if you want to learn more about South African wines, Tim James “Wines of the New South Africa” is an informative reference.

WRO Columnist Emeritus Gerald Boyd provides regular book reviews in this space, writing from his so-called "retirement"

6