Once upon a time in the land of Oz there was a plan to establish a beachhead for Australian wine in California, from whence the Aussies would take the American wine market, the largest market for wine in the world, by storm. Funded in part by the Australian government, the plan seemed to work.

Aussie Shiraz was going to be the next big thing in wine, and for a time it was. Americans, particularly Californians, were drawn to the ripe, plush fruit aromas and textures of these big, bold red wines from Australia. Even better, the exchange rate favored the American consumer and thus high-quality red wine from Australia was relatively cheap.

Large Australian wine companies such as Penfolds, Wolf Blass, Rosemount Estate, Lindemans, Hardys, Peter Lehmann and Jacob’s Creek aggressively expanded their reach into the United States and threatened to seize a sizable chunk of the market share, primarily taking it away from the dominant California wineries.

Large Australian wine companies such as Penfolds, Wolf Blass, Rosemount Estate, Lindemans, Hardys, Peter Lehmann and Jacob’s Creek aggressively expanded their reach into the United States and threatened to seize a sizable chunk of the market share, primarily taking it away from the dominant California wineries.

Then a funny thing happened: The bottom fell out. First, the Australian wine industry began to cannibalize itself. Mergers and acquisitions blurred the lines between long-established brands that once competed fiercely to establish identity, only to find in the long run that yesterday’s competitor was today’s stablemate.

Then quality, at least at the bigger Australian wine companies, took a hit as executives became increasingly concerned with return on investment. This was followed by a grape glut, which put downward pressure on prices. And, finally, California wineries fought back, generating new tiers of existing brands that could compete in the arena of price and quality. That the exchange rate on the dollar swung in favor of the Aussies only exacerbated the problem for the Australian wine producers trying to maintain their hard-earned share of the U.S. market.

In the end, the grand plan fizzled and the Australian wine experiment in the United States appeared to be on course for a giant boomerang. In one sign of abject failure, a large Australian wine company recently destroyed millions of dollars in back inventory it had been unable to sell. In short, Aussie wine in the U.S. market was a train wreck.

So it was with a bit of skepticism, and also a dash of curiosity, that I agreed to sit down recently with Australian winemaker Peter Fraser and taste his wines from Yangarra Estate Vineyard, a 400-plus-acre spread in the McLaren Vale region of South Australia. Fraser, who has an impressive track record at multiple wineries in South Australia, has been at the helm of Yangarra Estate since the property was purchased by the late Jess Jackson in 2000.

Jackson, an American, made his mark in wine with the popular Kendall-Jackson brand, but he was also a global visionary who purchased numerous wineries in Italy and France, and eventually Yangarra in Australia. Jackson probably never got his due for efforts to improve the breed, but in his later years he worked steadfastly to focus his wineries on better vineyard sources and state-of-the-art winemaking.

Yangarra, for example, began farming its vineyards organically and biodynamically in 2008, and was certified biodynamic in 2012.

“We were looking for greater purity of expression from the vineyards,” Fraser explained. “And we wanted to enhance the minerality and elegance that is inherent in many of our wines.”

There is no easy transition to biodynamic farming, for it requires biodiversity that involves the presence of farm animals, composting, and strict attention to the cycles of the moon. Few wineries in Australia have gone to the trouble, though Fraser cites the iconic Cullen winery of Margaret River in Western Australia as a good example.

There is no easy transition to biodynamic farming, for it requires biodiversity that involves the presence of farm animals, composting, and strict attention to the cycles of the moon. Few wineries in Australia have gone to the trouble, though Fraser cites the iconic Cullen winery of Margaret River in Western Australia as a good example.

In Fraser’s telling, the expressions of the various soils throughout the vast Yangarra estate are what make the wines compelling and unique. Of the 400-plus acres, 250 are planted to grape varieties typically found in the southern Rhone Valley of France. The soils range from huge ironstone deposits, which impart a distinct minerality to the estate’s Shiraz, to alluvial and sandy soils where bush-vine (with no trellis system) Grenache is planted.

Then there is the human element. As the winemaker, Fraser dissents from the doctrine of ripeness practiced by many of his Aussie brethren. There is no big blast of alcohol from the Yangarra wines, a departure from the norm of Australian Shiraz. Fraser works studiously in the vineyards and the cellar to control the alcohol level in the Yangarra wines.

When he makes the decision to harvest “I am looking for texture and elegance as much as flavor” Fraser explained. The Yangarra wines are impeccably balanced, including a luscious Viognier, which is typically made in an ultra-ripe style throughout the New World. The Yangarra Viognier could easily pass for French in a blind tasting.

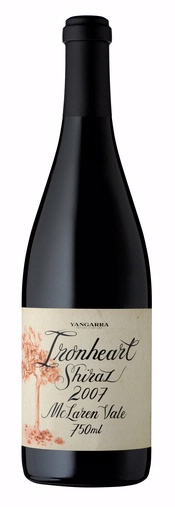

For the money, the Yangarra wines deliver the sort of price/quality ratio that helped create demand for Australian wines in the first place. The Viognier and a delicious Roussanne each retail for $25, and the flagship Old Vine Grenache is $32. There is but one truly budget-busting wine in the Yangarra portfolio and that is the Ironheart Shiraz that retails for $100, a price that reflects both its unique characteristics and its limited availability. A superb GSM blend (Grenache, Syrah and Mourvedre) reminiscent of Chateauneuf-du-Pape is a palatable $28.

As I tasted each wine in the lineup, I was impressed by the brilliance versus the cost and it occurred to me Yangarra, and wineries of its ilk, may well be the future of Australian wine in the U.S. market. It would be a very bright future, indeed.

Follow Robert on Twitter at @wineguru.

8