I am old enough to remember when Syrah was going to be the next big thing on the American wine scene. And not just Syrah but Viognier, Roussanne, Marsanne, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, et al. These are the so-called Rhône-style wines championed by contrarian American winemakers attempting to break away from the crowded field that occupied the high ground of Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, America’s two most popular wines.

I am old enough to remember when Syrah was going to be the next big thing on the American wine scene. And not just Syrah but Viognier, Roussanne, Marsanne, Grenache, Grenache Blanc, et al. These are the so-called Rhône-style wines championed by contrarian American winemakers attempting to break away from the crowded field that occupied the high ground of Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, America’s two most popular wines.

It’s hard to say who exactly led the way. Winemaker Gary Eberle, for example, brought syrah to California’s Central Coast. Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon abandoned his passion to make world-class Pinot Noir to work the Rhône grape varieties that appeared to be better-suited to his climate and soil. Both found success that reverberated around the wine world. Grahm ended up on the cover of the popular wine publication the Wine Spectator, and other winemakers drawn to the Rhne movement — Steve Edmunds and Sean Thackrey, to name just two — basked in the glow. An organization called the Rhône Rangers was formed to promote the Rhone-style wines, and the Hospice du Rhône, a festival that draws winemakers and fans from around the world for tastings and seminars, blossomed in Paso Robles, California. Yet somewhere along the way, the Rhone movement lost its mojo. Much like Pinot Noir before the movie "Sideways," Syrah became a hard sell.

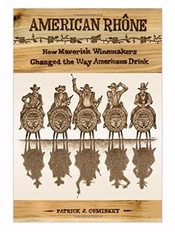

Journalist Patrick Comiskey, however, never lost his passion for either the true Rhône wines produced in the Rhône Valley in the south of France or the American Rhônes being made primarily in California and Washington. Comiskey, a writer and critic for Wine & Spirits magazine, has penned the definitive work on the Rhône movement, "American Rhône, How Maverick Winemakers Changed the Way Americans Drink."

Journalist Patrick Comiskey, however, never lost his passion for either the true Rhône wines produced in the Rhône Valley in the south of France or the American Rhônes being made primarily in California and Washington. Comiskey, a writer and critic for Wine & Spirits magazine, has penned the definitive work on the Rhône movement, "American Rhône, How Maverick Winemakers Changed the Way Americans Drink."

Comiskey, a gifted writer and storyteller, spent the better part of six years — by his estimation — researching the topic, conducting interviews, tasting the wines and eventually writing the book. With an exceptionally good eye for nuance, Comiskey is at his best when depicting the range of personalities — many, if not most, of them eclectic — who have put their stamp on the American Rhône movement. My only quibble with the book is the subhead on the cover. The American Rhône movement has stalled and seems to be in need of a spark. Could he be that spark?

Whether a fan of Rhône wines or not, "American Rhône" is an entertaining and educational read. It might even inspire devotees of Cabernet and Chardonnay to give the American Rhônes another shot.

8