When Prussian immigrant Charles Krug established a winery in St. Helena in 1861, he was laying the groundwork for the future. Krug was the first Napa Valley grower to produce vintage-dated varietal wines, a groundbreaking advance that helped launch the California wine industry.

When Italian immigrants Cesare and Rosa Mondavi purchased the winery in 1943, they worked with their two sons, Robert and Peter, to bring the winery back to prominence. After Cesare’s death in 1959, Robert and Peter continued developing the estate until Robert left to found his own winery in 1965.

Peter strove to balance innovation with tradition. He was the first in the Napa Valley to introduce French oak barrels. He was an early pioneer in the use of glass-lined tanks, and was also one of the first to invest in cold fermentation to maintain freshness in white wine.

Peter strove to balance innovation with tradition. He was the first in the Napa Valley to introduce French oak barrels. He was an early pioneer in the use of glass-lined tanks, and was also one of the first to invest in cold fermentation to maintain freshness in white wine.

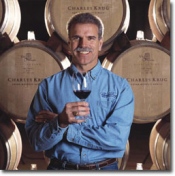

Now that Peter is in his nineties, the family owned companies — Charles Krug and CK Mondavi — are being run by his sons Marc and Peter Mondavi Jr., who are, they say, ‘literally betting the farm on the future.’ The family is midway through a ten-year, $21.6 million project that includes replanting their 850-acre estate with Bordeaux varietals selected for the specific soil profiles in the vineyards.

They also are in the process of converting to sustainable, organic agriculture: several vineyards have already received organic certification, with others soon to follow, and by the next harvest the Peter Mondavi family will be among the most extensive organic landowners in the Napa Valley. Among the multitude of projects they have undertaken is the restoration of fallow acreage with native vegetation, and the renovation of historic buildings on the property.

My chat with Peter Mondavi Jr.:

Q: For two generations the Charles Krug story has been a story of brothers: first your dad, Peter, with your uncle, Robert, and now that your dad is in his 90’s it’s you and your brother Marc who are running the show. How does the fraternal division of labor work with you, and are sibling relations cordial?

A: One reason it works for us is that we’re like night and day. I tend to be more analytical, and Marc is, well, he’s the total opposite. The fact that we’re so different helps balance it out. Since we have two brands, we’ve divided it up neatly: I have total responsibility for Charles Krug, and he has total responsibility for CK Mondavi. The two brands are a reflection of our two personalities, because we think it’s important for a family run wine business to give each brand a family personality. This works out well for us because each of our brands has a different personality. Charles Krug, for example, requires much more detail, which is the kind of thing I’m good at.

Q: So many family wineries have been sold lately — Duckhorn, Firestone and Stag’s Leap — come to mind as the most recent ones. Since Charles Krug is now one of only a couple of wineries to remain in the same family hands since the early post-Prohibition era, does this shift away from the traditional family owned wineries make you feel like a dying breed?

Q: So many family wineries have been sold lately — Duckhorn, Firestone and Stag’s Leap — come to mind as the most recent ones. Since Charles Krug is now one of only a couple of wineries to remain in the same family hands since the early post-Prohibition era, does this shift away from the traditional family owned wineries make you feel like a dying breed?

A: Most definitely, though we’re by no means dead! I think it’s just us and Trinchero that are the only producers of any size left from that early generation of wineries. But in one way this plays into our hands, because the distributors are beginning to appreciate family wineries.

Q: Why is that?

A: When a winery sells out, the new owners may just align themselves with their own distributors. For a family owned business, the distributor has to lose the right to sell that brand — they aren’t going to just be ousted.

Q: And are you happy with that status quo?

A: In general, yes. Most of our distributors around the country have been with us for decades.

Q: In 1975 the farm workers at Charles Krug voted for United Farm Workers representation in what was one of the first elections under the new farm labor law. In 2006, your winery fired thirty employees after announcing you were bringing in an outside management company. The UFW filed a complaint charging that the company failed to renegotiate the contract in good faith, and it called for a boycott of Charles Krug and CK Mondavi wines. Has that all been resolved yet?

Q: In 1975 the farm workers at Charles Krug voted for United Farm Workers representation in what was one of the first elections under the new farm labor law. In 2006, your winery fired thirty employees after announcing you were bringing in an outside management company. The UFW filed a complaint charging that the company failed to renegotiate the contract in good faith, and it called for a boycott of Charles Krug and CK Mondavi wines. Has that all been resolved yet?

A: I don’t know if the boycott is still on. The case itself is still in discussion at the state level.

Q: Earlier this year you were one of the people featured in Vanity Fair’s ‘Green’ issue for your commitment to organic farming. What are some of the best things wineries are doing for the health of the planet (in addition to providing us with so much drinking pleasure, of course)?

A: I think Napa is doing good things in the way of organic and sustainable farming. More and more producers are getting involved. Even many of the ones who aren’t certified are virtually organic. Things like cutting back on pesticides and herbicides are better for the land, better for the health of the people who work in the vineyards, and just generally better for the planet.

Q: What are some of the worst things wineries do to the health of the planet?

A: It isn’t just wineries, but shared among all industry is the amount of waste generated. Of course, I’m not talking about things like skins and other grape residue, all of which gets recycled one way or another. I’m referring to the vast amount of packaging; all the stuff that comes into a winery, and goes out of it for that matter. There’s no doubt that we could all do better with recycling and consolidating. And when wine is shipped there’s the issue of ‘food miles’ [the distance food, or in this case wine, travels before it reaches the consumer — one assessment of the environmental impact of transporting comestibles]. Energy is probably another big area we could improve. Wineries use a tremendous amount of things like heat and refrigeration. Some people are putting in solar cells, photovoltaic cells, which is probably one of the better ways to improve things.

Q: If you could never again have a bottle of wine made by someone named Mondavi, what would you drink?

A: My cellar is very eclectic. But it is mostly Napa Valley wine, which I have partly from curiosity, partly because it’s what I like to drink.

Q: Do you drink it for enjoyment or research?

A: Both. Let’s say there are probably 400 Napa wineries, each of which produces at least two different wines. If you do the math on that, per year I’m never going to be able to know everything that’s out there. But also, they are so stylistically different, and today there are virtually no really bad Napa wines. Of course some may be too tannic, or whatever, but they’re essentially all very good. I’m rarely disappointed.

A: Both. Let’s say there are probably 400 Napa wineries, each of which produces at least two different wines. If you do the math on that, per year I’m never going to be able to know everything that’s out there. But also, they are so stylistically different, and today there are virtually no really bad Napa wines. Of course some may be too tannic, or whatever, but they’re essentially all very good. I’m rarely disappointed.

Q: If you had to live in some other country, which one would you choose?

A: It would have to be Italy. Obviously my grandparents came from there, so that’s part of the attraction. They were from the Marche region. But over the years Italy has become the single country I love the most. I love the countryside, I love the food. They know how to enjoy life over there. Definitely, it would be Italy.