American wine consumers contend with many mysteries, some new and some that have been swirling around for years. One of the most enduring is why American wine consumers never took to German wines. Granted, interest and sales are not as weak as they once were, but Americans are still not high on German wines or, for that matter, Rieslings and Riesling-like wines in general.

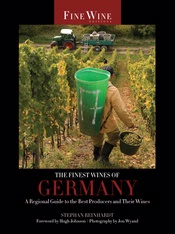

Sensing a slight glimmer of rising interest, the University of California Press has released The Finest Wines of Germany, the latest in its excellent Fine Wine Editions series. The author is German wine writer, Stephen Reinhardt whose prose on the wines of his homeland is augmented by the appealing color photographs (and portraits of German winemakers) by  noted photographer, Jon Wyand. Artfully composed, Wyand’s photos add an appeal not often seen in wine books. In his “Author’s Acknowledgements,” Reinhardt said about Wyand, “I had never seen German wine producers looking more relaxed or more themselves in front of a camera.”

noted photographer, Jon Wyand. Artfully composed, Wyand’s photos add an appeal not often seen in wine books. In his “Author’s Acknowledgements,” Reinhardt said about Wyand, “I had never seen German wine producers looking more relaxed or more themselves in front of a camera.”

Famed British wine writer Hugh Johnson provides a rambling and somewhat obscure Foreword, eventually veering back on course by taking the German government to the woodshed for “an act of astonishing self-harm (perpetrated) by a government in thrall to demotic ideas.” Johnson’s over-wrought scorn is aimed at a system where “quality as a concept was abolished and replaced by degrees Oechsle” [in other words, sugar content].

Starting in 1972 and running for almost three decades, the German norm was so sweet and insipid that its greatest former fans avoided it, claims Johnson. A part of that fan base was no doubt American wine drinkers who shied away from German wines, since the word then was that all German wines were sweet. The irony here is that about the time this injustice was being foisted, Americans were talking dry but drinking sweet. Eventually, Johnson does sort of get back on track, claiming that Germany is the “acknowledged source of the world’s great white wines.”

I suppose that means white Burgundy is chopped foie?

But I digress. “The Finest Wines of Germany” follows the same format of the other seven books in the series: Foreword, Preface, a small section on winemaking and grape growing, and The Finest Producers and Their Wines, with this last section making up the bulk of the book. Each of the 70 German wine producers chosen by the author is given a small profile, including a facts box and tastings notes on three to five wines, all of which Reinhart says were tasted on visits to the estates between August 2010 and January 2012.

Why just 70 producers from a total of 24,000, you may ask? Reinhart concentrates on VDP producers, Verband Deutscher Pradikatsweinguter, a tongue-twister that translates to the “Association of Pradikats wine Producers.” His key words for evaluating wines of this small group are “consistent and inspiring.” The group of 70 was drawn from wine producers in 10 of Germany’s 13 wine regions: not Saale-Unstrut, Hessische Bergstrasse, Mittelrhein. “I could not find a producer whose wines are consistently inspiring enough to merit a profile.”

For a wine consumer’s first foray into the somewhat complex area of German wines, Reinhart offers a concise primer in “Classifications, Styles and Tastes: Understanding German Wine.” This short section explains the difference between a Spatlese and an Auslese wine, in semi-technical and gustatory terms. And the author talks about the “implied” (my word not his) quality of VDP wines, from an association of producers at the Pradikat level.

I found it difficult to understand “Understanding German Wine.” The author uses the word “typical” to describe wines he believes are representative of a region or style. But if the reader doesn’t know the wines, then “typical” is a meaningless adjective. On the plus side, the publisher uses acres rather than hectares, recognizing that its readership hasn’t quite gotten the hang of metrics yet. Reinhardt does offer a good explanation of the levels of Pradikatswein (Kabinett, Spatlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese, Trockenbeerenauslese, Eiswein)) even though the explanations are more technical than most consumers care about: “Spatlese must be at least 76-90 degrees Oechsle and at least 7% ABV.”

The book’s glossary does not define ABV (Alcohol By Volume), but does give a general definition of Oechsle, without providing a formula for converting Oechsle to Brix, the scale commonly used by American wine producers. It’s a complicated formula, but if you are trying to understand the grape ripeness in terms of Brix, it would be helpful to know how to get from Oechsle to Brix, or even Baume, the French term. American wine drinkers wanting to learn about German wines probably will not think twice about these small criticisms.

“The Finest Wines of Germany” is a good guide to German wines that adds the human side of wine through the collection of charming photographs.

Gerald Boyd, Columnist Emeritus for Wine Review Online, will return from his so-called "retirement" periodically with book reviews in this space, so stay tuned. Michael Franz

6