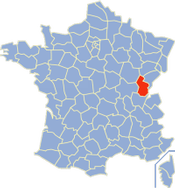

In early March, winter’s cold breath still huffs at the windows, and the garden lies silent and bruised by frost. This is the moment when wine lovers might plan a winter getaway to Australia, or Argentina, or some other summery viticultural region in the southern hemisphere. But let me suggest another type of vinous adventure: Pack up some thermal underwear, extra gloves and a pair of warm boots, and head for the Jura, France’s smallest wine region. In this pastoral land that rolls across the Alpine foothills between Burgundy and Switzerland, you’ll discover a lovely and distinctly un-touristy part of France, plus you’ll get to taste some really cool wines.

underwear, extra gloves and a pair of warm boots, and head for the Jura, France’s smallest wine region. In this pastoral land that rolls across the Alpine foothills between Burgundy and Switzerland, you’ll discover a lovely and distinctly un-touristy part of France, plus you’ll get to taste some really cool wines.

You may have run into a Jura wine or two at some point in your drinking life, but if your experience is like mine was, your knowledge of them is probably pretty limited. And isn’t that one of the beauties of wine-focused travel–that you are introduced to vins, vinos, vinhos, and weins that you’d probably never encounter at home?

Last January my husband, Paul, and I flew into Geneva, picked up a rental car, and headed west towards the Jura. As we coasted down the mountain pass into France snow was falling and the air was frigid. Winters in the Jura are chillier than in Burgundy, and that extra blast of cold weather contributes distinctive searing acidity to the grapes. In the best wines those acids will be balanced by the sweetness of fruit that’s been fully ripened during the Jura’s typically long, dry, warm  summers. And this notable equilibrium–sweetness balanced by acidity–is one of the most compelling hallmarks of good Jura wine. The best stuff is refreshingly crisp without being tart and thin, with fruit flavors that are fresh and straightforward rather than densely concentrated.

summers. And this notable equilibrium–sweetness balanced by acidity–is one of the most compelling hallmarks of good Jura wine. The best stuff is refreshingly crisp without being tart and thin, with fruit flavors that are fresh and straightforward rather than densely concentrated.

Another distinctive characteristic of Jura wines is their pronounced palate-pleasing minerality, a result of the region’s fossil-rich soils composed mostly of multi-layered clay and limestone deposits, with outcroppings of marl (a sedimentary amalgam of calcium carbonate and clay). If you’re unsure what the oft used but ephemeral term “minerality” really means when applied to wine, chances are you’ll taste it in the Jura.

Most visitors who come to the Jura find the wines strikingly unfamiliar. Aside from Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, which are shared with neighboring Burgundy, the region’s grapes are unknown to most of us. The native white varietal is Savagnin (sah-vah-nee-an), while the reds are Troussau (troo-so) and Poulsard (pool-sahr). Savagnin produces the famous Vin Jaune of the Jura, a unique wine that is aged for six years in old Burgundian barrels. A space of air is deliberately left above the wine, allowing a protective film of yeast to form across its surface.  Slow oxidation occurs, permeating the wine with aromas and flavors somewhat reminiscent of sherry (but unlike sherry, Vin Jaune is not distilled).

Slow oxidation occurs, permeating the wine with aromas and flavors somewhat reminiscent of sherry (but unlike sherry, Vin Jaune is not distilled).

Vin Jaune can be an utterly fascinating wine, but you have to give it a chance: To the uninitiated, its flavors can seem weird and rancid, but once your palate adjusts to that, a unique, seductive intrigue kicks in. The best wines are distinctly nutty, with hints of curry-like spices, and they can be wildly complex. Every once in awhile comes a wine makes you sit up and go “Wow!” For the cognoscenti, Vin Jaune  can be a truly satisfying aperitif wine (serve it with nuts and crackers), but in truth it’s tricky to find great food matches for this wine. One sure taste treat is to pair Vin Jaune with the region’s celebrated Comté cheese.

can be a truly satisfying aperitif wine (serve it with nuts and crackers), but in truth it’s tricky to find great food matches for this wine. One sure taste treat is to pair Vin Jaune with the region’s celebrated Comté cheese.

Vin de Paille, the Jura’s other renowned white wine, is a rare nectar made from grapes that have dried for a minimum of 6 weeks on straw (paille, pronounced “pye”), or on wicker racks, or by hanging from rafters, until the juices are sweet and concentrated. After the grapes are pressed, the wine is aged for three years in small barrels.

Chardonnay is as indigenous a varietal here as it is next door in Burgundy, but most of Jura’s Chardonnay tends to be noticeably different from its cousin to the west. Typical Jura Chardonnay might be off-putting at first, with its jolt of sherry-like oxidation contributed by the veil (voile) of yeast that sits on top of the wine in its barrel. But one soon gets used to the unfamiliar taste and begins to appreciate the savory complexity lingering in the wine. When Chardonnay is made in more traditional fashion (without the voile) it can be markedly floral, with a layer of stony minerality, and assertive, ultra refreshing acidity. The very best Chardonnays are stupendous–Burgundian in their intensity and flavor profile. Savagnin and Chardonnay are often merged together in a savory blend which is sometimes called “Tradition” and is well worth sampling.

White wine is the calling card of the Jura, but the region also turns out distinctive reds and rosés as well as some excellent Crémants. I’ll discuss these in a future blog, and give a couple of suggestions of places to eat and stay, as well as specific labels to look for. And I’ll also tell you why winter is the best time to visit the Jura.

7