In 1967 Alexis Lichine released his Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits, followed a few years later by Hugh Johnson’s seminal The World Atlas of Wine. Those two wildly successful wine reference books started a trend in wine books that included an array of encyclopedias and atlases. Many of those references are out of date now, such as Johnson’s The Atlas of German Wines, last revised in 1993.

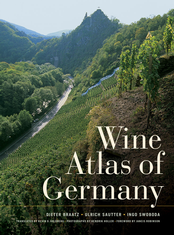

But there’s now reason for lovers of German wines to rejoice; a trio of German wine writers has released Wine Atlas of Germany, a meticulously researched and sumptuously illustrated guide to one of the world’s greatest and under-appreciated wines. The authors of this new book are  Dieter Braatz, a magazine editor and author of a guide to Germany’s best wine estates; Ulrich Sautter, author of Wein A-Z, and Ingo Swobada, co-author of Riesling. Hendrick Holler gets deserved credit for the precise and gorgeous color photographs that support the text.

Dieter Braatz, a magazine editor and author of a guide to Germany’s best wine estates; Ulrich Sautter, author of Wein A-Z, and Ingo Swobada, co-author of Riesling. Hendrick Holler gets deserved credit for the precise and gorgeous color photographs that support the text.

The time is right for this atlas, because the most current atlas of German wine, by British writer Stuart Piggott, was released 18 years ago. So it’s safe to say that a few things have changed with German wines over the last two decades, not the least that the hierarchy of German wine now includes the regions of Saxony and Salle-Unstrut, in the former East Germany.

Besides an in-depth peek at German wines not previously explored in an English-language text, Kevin D. Goldberg, the book’s translator, describes the changes in the complex German wine laws since 1971 and the complications of translating certain German viticulture and enology terms, such as Grosslage and Einzellage, contributing to better understanding by those who encounter German wine labels. This may seem like a small point, but a good translator can make a world of difference in explaining what is in the writer’s mind. (Gabriel Garcia Marquez, author of the Nobel Prize-winning novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, maintains that the English translation by Gregory Rabassa to be superior to his own Spanish-language original.)

Fans of German wine know that style has historically been given more attention than the concept of terroir. For years, the wine world shrugged its collective shoulders at the mention of the French term terroir to explain variations in quality separating some vineyards from others. Lately, though, a growing number of growers and winemakers have embraced the concept of terroir, including the Germans. The authors explain that, with the passage of a resolution in 2012 by the Confederation of Prädikat Wine Estates (or VDP), a number of things have changed such as the acceptance of the significance of terroir rather than wine style.

The importance of these recent changes in the classifications of German wine are stressed by the authors as a way to better understand the state of present day German grape growing and winemaking. The introductory chapter, entitled, “What Makes a Vineyard Unique,” provides a plausible answer to the question of how vintners develop a reputation for their wines so that consumers are willing to pay a premium price “for a bottle endowed with a little piece of earth.”

Other introductory material includes a short history of winegrowing in Germany followed by a current classification of German wines, including more information on the VDP classifications and then the obligatory list of wine grapes. It’s fun to scan the list, picking out unfamiliar wine grapes such as Acolon, Cabernet Mitos (a cross between Lemberger and Cabernet Sauvignon) and Dunkelfelder (No, not Dornfelder). A sidebar in the chapter on history provides an incomplete explanation of Oechsle, the must density measuring system used by German winemakers, that is a mystery to just about everyone else. There is a chart showing the minimum must weights in Oechsle for Qualitatswein and Pradikatswein (Spätlese, Auslese). But for the curious wine person familiar with other scales such as Baume (Australia) or Brix (United States), there is no formula to convert Oechsle to either scale.

The bulk of the text is a region-by region account, complete with history, climate, sites and soils and the author’s picks for “The Best Vineyards…” in any of the 16 regions. Wine fans will recognize at least half of the wine regions, with such familiar names as Mosel, Saar, Ruwer and Rheingau. The other regions like Baden, Taubertal and Hessische Bergstrasse are less familiar. Except for the more common Mosel and Rhein wines one is likely to find in most major U.S. markets, the others may require some serious searching.

For American wine drinkers, use of the word “vineyard” in a title is a bit misleading, since the term usually applies only to the site where grapes are grown. In this atlas, “vineyard” means so much more. In addition to vineyard data, each “Best Vineyard” profile includes important producers and a brief general description of the wine made from grapes grown in different soils. This is an unusual and welcome addition that speaks directly to the new German emphasis on the importance of terroir.

The last 55 pages of the atlas offer an extensive and informative Vineyard Index and a Village Index. Vineyard and village entries are listed by region/municipality/village and the map locator and vineyard listing, or in the case of a village listing, just a map locator. This is a useful and handy cross reference for anyone who has spent time–tracing with your finger–back and forth across a map, to find the village you were supposed to be in 30 minutes ago.

Wine Atlas of Germany is packed with precise detailed maps that zero-in on the area of choice, and plenty of beautiful full-color photos that tell their own story. The photo of an ingenious trackway, explains how growers and pickers negociate the steeply sloped vineyards along the Mosel and Rhein rivers. Or there’s the beauty of the fabled Wehlener Sonnenuhr vineyard above the sparkling Mosel river. This is a book packed with facts and information and well worth the price for the serious student of German wine.

Wine Atlas of Germany, Dieter Braatz, Ulrich Sautter, Ingo Swoboda; University of California Press, hardcover, $60. ISBN: 9780520260672

* * *

Gerald Boyd, Columnist Emeritus for Wine Review Online, contributes book reviews on an occasional basis from his so-called "retirement."

6