Earlier this month a $12 wine, Castello Banfi’s 2010 Centine, was voted the best red wine at the Ninth Annual Critics Challenge International Wine Competition held in San Diego.

To be voted best red is a high honor for any wine, but is absolutely extraordinary for one costing twelve bucks. Here’s an overview of the  process: First, two wine-writer judges taste the wine blind, that is, they do not know its identity or its price. To advance to the next round, one of the judges must award it a platinum medal based on its overall quality. Price is not a factor. A platinum medal means that the judge thinks it has a chance of being selected from over 600 red wines, some of which cost over $100 a bottle, as the best wine in the competition. [As it happens, the two judges in this case were Michael Franz and Ed McCarthy, both of Wine Review Online.]

process: First, two wine-writer judges taste the wine blind, that is, they do not know its identity or its price. To advance to the next round, one of the judges must award it a platinum medal based on its overall quality. Price is not a factor. A platinum medal means that the judge thinks it has a chance of being selected from over 600 red wines, some of which cost over $100 a bottle, as the best wine in the competition. [As it happens, the two judges in this case were Michael Franz and Ed McCarthy, both of Wine Review Online.]

Phase two is a taste off of over 50 red wines in all categories–Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Malbec, Bordeaux blends and so on–that other judges also felt might merit top honors. The 17 assembled judges–still blinded–taste the contenders and vote for top honors.

Can you imagine how hard it is to reach consensus among 17 highly opinionated wine writers?

Frankly, the judges’ selection of the 2010 Centine, a blend of Sangiovese (60%) and equal parts Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, as the best red wine does not surprise me. I’ve been a fan of this wine since I first tasted it over a decade ago, calling it my “Wine of the Year” in 2006. As Robert Whitley, the competition’s organizer, mentioned after the winner was revealed, “The great thing about Centine is that, unlike many other similarly priced wines, is a real wine, not a concocted one.” The vast majority of the grapes come from Banfi’s 7,100-acre property (Manhattan island is 8,900 acres), although they do buy some grapes for this wine. Unlike many inexpensive wines, it ages in barrels for a short period of time, a practice that increases complexity.

The Back Story

A little background about Banfi and their compulsive and unremitting focus on quality helps explain why this honor bestowed on one of their less prestigious wines should be no surprise.

The Mariani family, owners of Banfi, the importer of Riunite (which, by the way, was the leading imported wine in the US for 24 consecutive  years, from 1976-2000), had a vision to make a great Italian wine. They felt there was an opportunity in Montalcino whose now iconic wine, Brunello di Montalcino, was basically unknown in 1980. It is almost impossible to believe today, that as recently as 30 years ago, Brunello di Montalcino was a sleepy wine region with only about 80 producers and 1,500 acres under vine when it received its DOCG status, Italy’s highest wine categorization, in 1980. Now that its worldwide popularity has spread, everyone wants to get in on the act. At last count there were about 230 producers working 5,000 acres.

years, from 1976-2000), had a vision to make a great Italian wine. They felt there was an opportunity in Montalcino whose now iconic wine, Brunello di Montalcino, was basically unknown in 1980. It is almost impossible to believe today, that as recently as 30 years ago, Brunello di Montalcino was a sleepy wine region with only about 80 producers and 1,500 acres under vine when it received its DOCG status, Italy’s highest wine categorization, in 1980. Now that its worldwide popularity has spread, everyone wants to get in on the act. At last count there were about 230 producers working 5,000 acres.

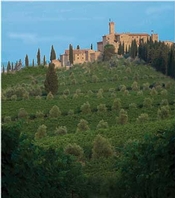

In 1978, the Mariani family purchased 7,100 acres in the southern aspect of the region, creating Castello Banfi, the largest privately owned contiguous wine estate in Europe at the time. (One-third of the estate is planted with vines, but not all of them lie within the Brunello zone.) The local population was horrified, thinking that these interlopers would be bottling Brunello with Riunite-like screw caps. Little could they have imagined how Banfi would aid the entire region.

Clonal Selection Project

There are literally hundreds of clones of Sangiovese, the one grape allowed for Brunello di Montalcino. Banfi wondered which ones were best suited to the unique climate and terroir of Montalcino. By contrast to the situation in France, where the government supports viticultural research, there was no government support within Italy or Tuscany to answer the question. So Banfi undertook the project of figuring out which clones of Sangiovese (a.k.a. Prugnolo Grosso) worked best in Montalcino.

From the over 600 known clones already present in Montalcino, Banfi used 180 that they felt were genetically distinct to plant experimental vineyards. After a decade of making small batches of wines from those 180 clones, they winnowed the field down to 15, which they registered with the European Union (EU). Of the 15, they are gradually replanting their vineyards with three, named BF 30, (a clone they actually found within their vineyards, hence BF for Banfi), Janus 10 and Janus 50.

Instead of keeping their research secret, Banfi actually shared it with all of the other Brunello producers with the idea that an overall increase in the quality of Brunello would help them in the long run. That forward-thinking philosophy reminds me of Robert Mondavi’s vision in the 1970s of promoting California wine in general rather than his wines in particular, when he noted, “My challenge is to get people to drink California wine. Once they do that, plenty [of people] will drink mine.” Now many producers use these clones of Sangiovese for their Brunellos, according to Lars Leicht, a Banfi spokesman.

Tasting the three clones separately and then as the final blend is a dramatic example of how the finished product is greater than the sum of its parts. The wine made from the BF 30 clone, generous and approachable, delivers a deep core of dark fruit and earth characteristic of Brunello. It’s a rounder and sweeter expression of Brunello. By contrast, the Janus 10 clone produces a leaner wine with a far firmer structure. Less generous, it still conveys a dark minerality. The still more structured Janus 50 clone adds a distinctive spicy component. The least fruity of the three, it is almost impenetrable. In the blend, the fruit, minerality and structure all come together seamlessly.

The Vineyards

With such a large estate, it comes as no surprise that all of Banfi’s vineyards do not produce the same wine, even from the same clones of Brunello. After solving the clone question, Banfi put their vineyards under the microscope and studied them with the same intensity. Though located in one area of the Brunello zone and not spread out over the entire DOCG area, Banfi’s vineyards vary in elevation, climate, and soil composition from sandy to rocky. Indeed, they’ve identified more than 30 different microclimates on their estate.

Banfi makes three different Brunellos that reflect the differences in their vineyards. Their straight Brunello, a blend of wines from throughout the estate, is a classic representation of the DOCG zone. Their Brunello labeled Poggio alle Mura comes exclusively from their new clones and represents a more complex and sophisticated example of Brunello. It is consistently superb, well priced–at least for Brunello–and deserves to be in every Brunello-lovers’ cellar. Banfi’s flagship Brunello, their Reserva, Poggio all’Oro, which they do not make every year, comes exclusively from a single vineyard planted in 1982, before the results of the clonal  research were known. Poggio all’Oro demonstrates how critical site is, trumping everything else. As important as their clone research has been, Banfi has no plans to pull up the vines in Poggio all’Oro, although as they need to replant there, they are doing so with their new clones. As Rudy Buratti, Banfi’s chief winemaker, notes, “If it’s ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

research were known. Poggio all’Oro demonstrates how critical site is, trumping everything else. As important as their clone research has been, Banfi has no plans to pull up the vines in Poggio all’Oro, although as they need to replant there, they are doing so with their new clones. As Rudy Buratti, Banfi’s chief winemaker, notes, “If it’s ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Big is Not Bad–Indeed, It’s Good

In my opinion, one of the reasons that Banfi’s 2010 Centine won is because Castello Banfi is a large producer. Conventional wisdom is that small is better when it comes to wine and that big wineries make an “industrial” product. That may be true sometimes. But let’s look at the advantage the big producers have over the small ones.

Large producers can afford to be highly selective in what grapes go into which wines because they can stratify their production. They always have an outlet for wine that doesn’t quite meet their strict criteria. For example, Banfi bottled no 2001 Poggio all’Oro because they felt it did not meet their standards for that wine and they didn’t want to risk soiling its reputation. The wine from that vineyard went into the 2001 Poggio alle Mura and the 2001 straight Brunello, both of which were spectacular as a result. Similarly, Banfi has the option to include, in the blend that becomes Centine, Sangiovese that could legally go into their Brunello or their Rosso di Montalcino but is not quite up to snuff for those wines. For economic reasons, small producers just don’t have the option. They have to bottle all of what they produce under one label. They just don’t produce the volume to stratify the wines in the same way.

So while small might be better in some ways, size does still matter.

Questions or comments? Email me at [email protected]