Rias Baixas is located in Galicia in an area that is called “Green Spain,” which may sound like an oxymoron, but it’s real and it’s beautiful. The autonomous community of Galicia is probably the biggest part of Green Spain. Shaped roughly like a square that creates the north-west corner of Spain, it is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and north, Asturias and Castilla-León to the east, and Portugal to the south. In fact, Galicia has more in common with the Vinho Verde region of Portugal than other, warmer, drier wine regions of Spain. While you may not have heard of Galicia, I’ll bet you have heard of its capital city, Santiago de Compostela, whose Old Town was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985 and is the ultimate destination of pilgrims along the Camino de Santiago to the tomb of the Apostle James the Greater.

I was not surprised to learn that the Romans introduced grape growing, and winemaking to Galicia to the area. Wine production continued successfully until the phylloxera louse (imported to Europe on American grape cuttings in the mid-1800s) decimated vineyards in Galicia and most of Europe. Whatever recovery was made from this plague was then crippled by the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. The rebirth of Galician wine-making came in in the form of investment funds provided by Spain’s membership in the European Union in 1986. A look at the numbers for Rias Baixas from the Wine Regulating Council shows how quickly this appellation has grown. Comparing 1987 to 2017, the number of wineries grew from 14 to 184, grape growers from 492 to 5,550, acres of grapes planted from 585.6 to 10,000, and cases of wine produced from over 63,000 to over 2.6 million.

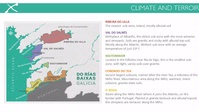

Rias Baixas gets its name from the inlets, or rias, made by the Atlantic into the coastline estuaries, where sea water mixes with fresh water fed by the Miño, Sil, Ulla and Lérez rivers. There are five sub-regions. The northernmost and  newest is Ribeira do Ulla, located just southeast of Santiago de Compostela. Val do Salnés, considered the birthplace of Albariño, is the oldest sub-region with the highest concentration of wineries. Soutomaior located at the head of the Rías de Vigo is the smallest sub-region. The last two, Contado do Tea and O Rosal, have southern borders on the Miño River dividing Spain and Portugal. Contado do Tea is east of O Rosal and is the warmest, driest and most inland of the sub-regions. O Rosal’s vineyards are terraced along the Miño as it flows into the Atlantic.

newest is Ribeira do Ulla, located just southeast of Santiago de Compostela. Val do Salnés, considered the birthplace of Albariño, is the oldest sub-region with the highest concentration of wineries. Soutomaior located at the head of the Rías de Vigo is the smallest sub-region. The last two, Contado do Tea and O Rosal, have southern borders on the Miño River dividing Spain and Portugal. Contado do Tea is east of O Rosal and is the warmest, driest and most inland of the sub-regions. O Rosal’s vineyards are terraced along the Miño as it flows into the Atlantic.

Although red grapes are allowed in the DO, white wines make up 99% of production. Twelve white varieties are allowed in the region, but Albariño represents 96% of the white grapes grown. Other allowed white grapes are Caiña Blanca, Godello Loureira (called Loureiro in Portugal), Treixadura and Torrontés. Red grapes allowed are Brancellao, Caiño Tinto, Espadeiro, Loureira Tinta, Mencía and Sousón.

Albariño is the only grape grown on a pergola system. It is an eminently practical system that optimizes use of the land while providing the best conditions for the star grape variety. The traditional pergola of the region has stone posts that provide the framework for the trellis, or parra, that supports the vines. Albariño is a vigorous vine that needs space to sprawl. The trellis allows the leaves to create a cover for the grape bunches and protect them from the sun. The open space below the trellis allows airflow to mitigate the heavy humidity of the region and protect the fruit from mildew. The pergola is high enough for people to walk under it. In the past, growers took advantage of the ground beneath to grow other crops.

While the pergolas are beautiful and provide hospitable growing conditions for the grape, they not so easy on the harvesters. First of all, as noted, the bunches hang from the overhead trellis as high as seven feet above ground, which means the harvester must stand on a harvest crate to reach the grape bunches hanging overhead. Each bunch is inspected, and any berry with an imperfection is removed from the bunch. The bunch is cut from the vine by hand, inspected once more for imperfections that will be cut out, then placed in a small plastic 40-pound crate required by the appellation rules.

Albariño is a versatile grape and several styles are allowed in the region. As Katia Alvarez, winemaker for Marin Codax says, “We can make different styles with one variety.” The Martin Codax Rias Baixas “Gallaecia” 2013 (E  & J Gallo $13.00) is a great example of a different style, although it may have been more an example of Alvarez’s winemaking skill and flexibility dealing with unexpected gifts of nature. Eighty percent of the grapes were affected by botrytis, leading to the creation of what might be the first late harvest Albariño. Alvarez and her crew had to act quickly to compete the picking to these grapes in two to three days because she said that botrytis “can turn ugly fast.” The night time humidity at harvest prevented the normal desiccation of grapes that occurs with botrytis, so the wine is dry, yet it has the characteristic aromas and flavors of a botrytis infection. It is an Albariño on steroids. The delicious honeyed aromas and flavors from botrytis highlight the grape’s floral character, and the wine is definitely dry and intense in the mouth. It would pair well with a pork roast.

& J Gallo $13.00) is a great example of a different style, although it may have been more an example of Alvarez’s winemaking skill and flexibility dealing with unexpected gifts of nature. Eighty percent of the grapes were affected by botrytis, leading to the creation of what might be the first late harvest Albariño. Alvarez and her crew had to act quickly to compete the picking to these grapes in two to three days because she said that botrytis “can turn ugly fast.” The night time humidity at harvest prevented the normal desiccation of grapes that occurs with botrytis, so the wine is dry, yet it has the characteristic aromas and flavors of a botrytis infection. It is an Albariño on steroids. The delicious honeyed aromas and flavors from botrytis highlight the grape’s floral character, and the wine is definitely dry and intense in the mouth. It would pair well with a pork roast.

A lovely example of the ageing ability of Albariño is Pazo de Senorans Rias Baixas “Seleccion de Anada” Albariño 2010 ($64 European Cellars), a single  vineyard wine that spent three-plus years on the lees. According to winemaker Ana Quintela, this was “probably the best wine we have made.” It showed aromas of grapefruit zest and flavors of citrus and peach with a creamy mouthfeel and a long finish. Quintela noted that the “acid is as one with the fruit.” Indeed, it was seamless.

vineyard wine that spent three-plus years on the lees. According to winemaker Ana Quintela, this was “probably the best wine we have made.” It showed aromas of grapefruit zest and flavors of citrus and peach with a creamy mouthfeel and a long finish. Quintela noted that the “acid is as one with the fruit.” Indeed, it was seamless.

Adegas Valmiñor Rias Baixas DO, O Rosal “Davila” 2017 ($20, Kysela Père et Fils) is a blend of 80% Albarino, 15% Loureira and 5% Treixadura, a traditional style blend from O Rosal. The grapes are handled separately through harvest, cold maceration and fermentation. Albarino and Loureira spend two months on the lees in stainless steel tanks then the wines are blended and bottled. Tropical fruit flavors like pineapple and mango, along with grapefruit and an herbal note are round, creamy and a bit chewy in the mouth. This is full flavored wine that can hold its own with richly flavored food.

These are just a tiny example of different approaches to Albariño, a glimpse of this region’s possibilities. I have been a fan of Albariño for many years and being able to see its home just confirms my enthusiasm. Rias Baixas is breathtakingly beautiful, the bounty of its waters is wondrously delicious, and its native grape a precious gift. I can’t wait to go back. You should go, too.