This is a book about so much more than wine and winemaking. First and foremost it is an account of the development of California’s wine industry by someone who helped shaped it into what it is today, but additionally The Winemaker is a charming personal reminiscence of a life fully lived. Among the things that set this chronicle apart from other wine-themed histories is that the author’s own life parallels and echoes that of California’s post-Prohibition wine industry.

The lively description of Peterson’s childhood years spent on a farm in Iowa is almost as captivating as the account of his many contributions to the world of wine. These early chapters are set in an America that has all but vanished. Richard Peterson was born, in 1931, in Des Moines, Iowa, the son of a coal miner and grandson of Swiss and German immigrants. The evocative depiction of the hardscrabble everyday life in America during the Depression years is studded with poignant anecdotes–hauling water from the well for his father’s daily bath after work in the coalmine, for example (the family never had running water or an indoor bathroom  until Peterson left home for college). But challenging as things often were, this is in no sense a Dickensian tale of deprivation; on the contrary, Peterson describes his youthful years as having been a “wonderful childhood.”

until Peterson left home for college). But challenging as things often were, this is in no sense a Dickensian tale of deprivation; on the contrary, Peterson describes his youthful years as having been a “wonderful childhood.”

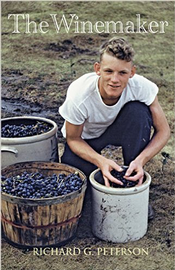

Peterson was introduced to winemaking at an early age. His father had been producing wine since the 1920s from Concord grape vines he’d planted on the family’s farm. When Prohibition came along, “Pops,” like other home winemakers across America, began purchasing grape “bricks” from California that were made by pressing the skins left over from freshly crushed grapes into “dry” bricks, and packaged with a label that read: Do not break up 5 grape bricks with the enclosed yeast pills and add 5 gallons of water with 10 pound of sugar, as this might ferment.

The author’s own first experience as a winemaker (when he was a freshman at Iowa State) is described in a humorous passage that begins with an impulse to make wine despite the fact that “I didn’t have the foggiest idea” how to do it. His father’s advice? “Smash the grapes all to hell, let ‘em spoil with the skins in the mess for awhile, then bottle it without the skins.” (“Pop had a sense of humor,” Peterson wryly remarks.) After more or less following Pop’s instructions, sealing the bottles with regular beer caps, then accidentally leaving one bottle on the back seat of his car one hot afternoon…well, you can imagine the explosive end to that experiment.

After finishing graduate school at UC Berkeley Peterson’s professional career officially begins when he accepts a job at Gallo in 1958 for $675 per month (double what winemakers were being paid at the time, we’re told.) As he enters the industry “at a time of surprising new beginnings,” we travel vicariously along with him observing the many stunning changes taking place in California’s wine industry, including the shift towards better grapes (did you know that almost all California white wines at the time were made from Thompson Seedless grapes?) This does not mark the beginning of Chardonnay’s supremacy–in 1958 there were fewer than 100 acres of Chardonnay in all of California–but Chenin Blanc was a distinct improvement over Thompson Seedless.

By the 1960s there was also a clear movement towards drier wines. Since the end of Prohibition, high-alcohol dessert wine had been outselling lower alcohol table wine 3 to 1, but now, Peterson writes, “The five-decade boom in dessert wine sales was collapsing while table wine sales were (unaccountably) growing rapidly.”

Another thing that was growing rapidly was the author’s winemaking skills, initially under the guidance of famed father-and-son vintners Andre and Dimitri Tchelistcheff, who became his friends as well as mentors. Peterson’s descriptions of fine-tuning his own sensory capabilities are particularly fascinating. Among the intriguing things he learned in those early years was that “It was fun to guess a wine’s pH by its taste, and I still do that fifty years later.” It surprises him, he says, that few other winemakers have made the effort to learn that skill. “To this day I believe tasting the natural chemistry of wine is a primary skill that every winemaker needs to master. Unfortunately, precious few do this, judging from the crudeness of today’s overly alcoholic and flabby wines.”

While Peterson’s affable and generous Midwestern personality is evident throughout the narrative he is by no means a pushover, and he is especially critical of underperforming winemakers. His real contempt, however, is reserved for “liquor sales people trying to sell wine,” and throughout a career that spans some fifty years he will butt heads with representatives from giant corporate entities, including Heublein, Seagram, and Allied-Lyons. Wine sales, he says, have been suffering at the hands of “liquor mentalities” since the repeal of Prohibition, and he notes that wine has always been best sold as an accompaniment to food “while liquor was sold only for its alcohol.” Throughout a career that spans some fifty years Peterson witnessed many examples of that “liquor mentality” mismanaging wineries in which he was involved, beginning with Beaulieu (“Heublein had single-handedly changed Beaulieu from the pinnacle wine property of America into just another Napa Valley winery,” he writes).

This is a memoir that should appeal to wine connoisseurs and neophytes alike. The voice is easygoing and conversational. There is very little technical wine jargon in the narrative, although readers who might want to expand their basic knowledge will appreciate the clearly written, simply defined footnotes conveniently positioned at the bottom of relevant pages (for example: “’Must’ is the name given to a mass of freshly crushed grapes, including pulp, juice, seeds and stems. ‘Pomace’ is the name for the waste solids left over after the juice and wine are removed from must.”)

“I am an engineer, a good taster, and I keep up with the chemistry and biochemistry of wine,” is how this vintner sums up his life’s work, but even here he is too modest. He might, for example, have added “inventor” to the list, for he invented many things that have benefited the world of wine, most notably the Peterson steel barrel pallet stacking system that is widely used throughout the wine industry today. And late in his career he could also add “expert witness” to his job resume, having participated in numerous wine related legal cases including lawsuits and insurance claims.

The Winemaker is packed with lively descriptions of Peterson’s family and colleagues, some of them warm and affectionate portraits (the Tchelistcheffs; Julio Gallo; his brother-in-law Gene Miller), others blisteringly dismissive (Andy Beckstoffer; Seagram’s plant manager Frank Jerant; NROTC Captain F. Moosebrugger).

What you will not find in this memoir, however, is much of anything in the way of facts or feelings about his private domestic life. If you’re looking for tidbits about his first marriage and subsequent divorce you won’t discover any details here, nor will you learn much about his second wife except that her name is Sandy. For that matter he is surprisingly circumspect about his two daughters, who get a proud, if brief, shout-out towards the end of the book, but considering how very successful his progeny are the reader might wish to know a little more about dad’s relationship with and influence on his daughters Heidi Peterson Barrett (winemaker for Screaming Eagle, Grace Family Vineyards, Dalla Valle plus her own brands La Sirena and Amuse Bouche), and Holly Peterson, Michelin three-star restaurant chef, and teacher at the California Institute of America at Greystone. Perhaps that will be the next book?