In the beginning, there was Ziliani. And Ziliani said “Let there be Franciacorta.” And there was Franciacorta. And it was good.

While there is much more to the history of the region’s wines, Franciacorta as we know it today is a thoroughly modern invention — quite out of character in the litany of Old World wine regions. Franco Ziliani was the winemaker for the Guido Berlucci estate who, in 1958, decided to make sparkling wine from vineyards in the glacially-formed hills at the south end of Lake Iseo. In rather rapid fashion over the intervening half century, Franciacorta has evolved to become Italy’s premier sparkling wine.

The Lake Country of Lombardy

The history of winemaking in the area stretches back to Roman times. Residents in the nearby city of Brescia (Brixia to the Romans) have long sought after the wines of what was called the Terra Franza Curta. Writers of four hundred years ago praised the character of the vini mordaci — “biting wines” of the region. In modern times, Franciacorta was established as a DOC in 1967, but not for its bubblies. Thanks to Franco Ziliani and other pioneering vintners with quality in mind, by 1991 the name of Franciacorta was accorded solely to the sparkling wines of the delimited region made in the approved methods. Franciacorta was elevated to DOCG status in 1995. The still wines of the region are sold as Terre de Franciacorta DOC or Sebino IGT.

Today, the range of Franciacorta wines is impressive. Wine lovers can sample a range of styles. Some are sold with familiar designations like Brut and Extra Dry that we associate with Champagne. The term Satén is unique to Franciacorta and used for wines bottled with less pressure than the standard bottlings. Many producers offer a very dry Non-dosato or Pas-dosé version as well.

Lake Iseo

The glacial geomorphology of the Alps is important in the understanding of the landscape of Franciacorta. During the Ice Ages of the last 2 million years, there have been periodic advances of large glaciers from the Alps of northern Italy. Similar to other parts of the world — notably the northern United States — these immense masses of ice carved out deep valleys. Along their courses, they plucked rocks and other debris from their valleys and pushed them southward during times of Alpine glacial advances. There were at least four major advances of the great ice sheets, and more minor fluctuations.

Today, we are arguably in one of the warm interglacial periods. The ice sheets began receding a mere 20,000 years ago — a blink of an eye in geologic time. The topography we observe today in the glaciated areas has been profoundly affected by the ice movements. In the case of Franciacorta, it is the jumble of debris pushed and piled up in front of the advancing ice that interests us. As the climate warmed and the glaciers retreated, they not only left the deep canyons now occupied by lakes but also the hills of their moraines.

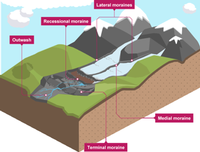

Glacial Landforms

Glaciers carry large amounts of debris as they move. Sand, clay, gravel, pebbles, cobbles and boulders can all me moved around as glaciers flow. Moraines consist of material transported by glaciers and subsequently deposited. When glacial advances cease and melting occurs, all these random sediments are dropped in place. There are several types of moraines. End moraines are sediments pushed in front of the glacier and a terminal moraine is created at the furthest extent of the glacial movement. Lateral moraines are composed of debris plucked from valley walls as glaciers move. Medial moraines occur when glaciers from adjacent valleys flow together and carry debris along in the middle of the now joined valley glacier. There are many other landforms unique to glacial recession, but the end moraine is the singular aspect that created the topography of Franciacorta.

The best vineyards in many classic winegrowing regions are on the hillsides, where the angle of the sun provides more photosynthetic potential for the vines and where gravity naturally drains water away. This prevents the vine from growing too vigorously and results in more intensely flavored fruit. In the case of Franciacorta, the vine-dressed hills were, in a geologic time sense, literally built by the glaciers yesterday. The random mix of sands, cobbles, gravels and clays combined with the fortuitous elevation and enhanced drainage, provide us with the vineyard source of Franciacorta. The large body of water of the lake moderates the local climate as well, ameliorating the extremes of summer heat and winter cold.

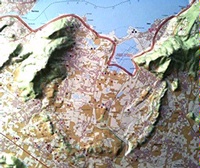

Relief Map of Lake Iseo and the arc of the Franciacorta Moraine

A look at the map of Franciacorta clearly shows the glacial moraine influence. As the glacier moved down the Val Camonica to the north and gouged out the 800-foot deep bed of Lake Iseo, the mountains on the east and west forced the glacier to push between them. The result is seen vividly on a relief map, with the arc of low hills – the end moraine of the glacier — now creating the habitat for the vines of modern Franciacorta.

The Morainic Hills and Vineyards of Franciacorta

We find a similar glacial moraine influence in other winegrowing regions of the lake country. Nebbiolo-based wines from Ghemme, Boca and Fara in the Novara Hills near Lake Maggiore are drawn from vineyards planted on moraines. Lake Garda is the largest and most famous of the big lakes and the sequence of moraines at the southern end of Garda support the vineyards of Lugana and Bianco di Custoza.

If you like the delicious freshness and vitality of good Champagne and other sparkling wines, give Franciacorta a try. The glaciers have done the heavy lifting to create the landscape and we get to reap the sensory rewards.