In just 30 years, New Zealand has grown from a virtual vinous non-entity to an international all-star for its distinctive Sauvignon Blancs. Its vineyards have also shown great potential as a source of other varieties. The Marlborough region on the north end of New Zealand’s South Island has been the center of this dramatic growth.

Although there is a century-long history of viticulture in Marlborough, modern commercial plantings in Marlborough began in the 1970’s thanks to the vision of the pioneering Marlborough growers. The early going was not easy. In addition to local opposition by farmers and foresters to vineyard planting, it took a few trials before vineyards were established. The plantings were more likely to be Müller-Thürgau than Sauvignon Blanc at the time, but experimentation was the order of the day, and many varieties were planted. It was not until the mid-1980’s that Marlborough Sauvignons took the UK market–and thence the world–by storm. Since then, the plantings have grown to the current 42,000+ acres of Marlborough Sauvignon, and the Wairau Valley, virtually bereft of vines 40 years ago, is now a vast vineyard area.

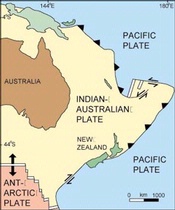

New Zealand — Where the Pacific Plate meets the Australian

What makes Marlborough such a distinctive growing region? Its advantage is tied to its underlying geology. The sunny climate and strong diurnal shift that allows the vivid Sauvignon Blanc flavors to develop is possible because of the rain shadow protection of the Southern Alps. The geologic story begins here. The earth’s surface is composed of tectonic plates that are in continual, albeit slow, motion. While we think of New Zealand as widely separated from Australia, the North and South Islands are actually situated on the edge of the Australian Plate.

The country we know as New Zealand straddles two moving segments of the planet’s surface — the Pacific and Australian plates. While the plate boundary lies offshore to the east of New Zealand’s North Island, it runs along the Southern Alps for most of the length of the South Island, cutting across the northern end in a series of fault-bounded valleys that includes the Marlborough winegrowing region.

The two plates are grinding past each other as they collide. The pressure not only continues to push up the Southern Alps some 30 feet per century, but also is pushing the west side of the South Island northward. It’s hard to keep track of one’s direction with so many moving parts. The fact is that the South Island is being torn asunder along the axis of the Alpine Fault. The movement is very rapid by geologic measures — about 10 inches a decade, which will add up to 16 miles of displacement in the next million years. Of course, the movements do not occur gradually, but in great bursts of pent-up energy that we experience as earthquakes. New Zealand overall is one of the most active seismic zones on earth. It has experienced some 90 earthquakes of 6.0 or greater magnitude in the last 200 years.

In addition to the geologic structure of the islands, glacial periods over the past two million years have had a profound impact on the land surface we observe today. During the glacial phases, large volumes of the world’s water supply were locked in ice and sea levels dropped hundreds of feet. As the glaciers receded, there were vast outpourings of melt-water charging through the river valleys, carving deeper channels and leaving gravel terraces above the newly-incised valleys.

The Alpine Fault on the South Island

Nestled within this geologic crucible are the fault-bounded valleys that form the Marlborough winegrowing region. The Wairau River Valley is the original site that spurred the growth of the New Zealand wine industry, and it remains the most important source of grapes. The geomorphology of the Wairau is complex and the resultant valley soils vary considerably. The Wairau River, engorged with glacial melt-waters, flowed out from the mountains, depositing a large alluvial fan on the western end of the valley. There are more gravels and sands on the western end and more clay components on the seaward side. The wide range of drainage capacities allows very different styles of wine to be made, with some sites emphasizing tropical fruit elements and others showing stronger citrus or herbaceous tones.

Vineyard on Terraces above the Awatere River

The success of the Wairau plantings has led to widespread vineyard development in the Awatere Valley that roughly parallels the Wairau to the south. The Awatere is higher in elevation, windy and somewhat cooler, but born of the same geologic heritage. The Awatere Fault experienced a strong earthquake in 1848 and the fault trace is easily visible on aerial photographs. These are archetypal New Zealand winegrowing sites, with the braided rivers flowing through broad, flat valleys beneath perched terraces of former riverbanks.

Aerial View of the Awatere Fault and River

In between the two major watercourses are a series of smaller areas named the Southern Valleys. These include the Fairhall, Omaka and Waihopi Rivers, which lie between the Wairau and Awatere. They are small watercourses that flow into the southern Wairau Valley, but have had a profound influence on the soils here. As they empty from steeper slopes into the flatter, broader valley, the rivers can no longer carry the same sediment load and have deposited a series of sands, gravels and clays that form alluvial fans along the south side of the Wairau. Thus, we have competing depositional forces with the alluvial fans of the Southern Valleys encroaching on the primary fan of the Wairau. This makes a very complex puzzle and is part of the reason why not only Sauvignon Blanc, but also Pinot Noir can grow well on some sites but fail to ripen in others.

Because of its marketplace success and a tradition of blending, Marlborough Sauvignon Blancs are often thought of as “all the same” in the minds of consumers. This is clearly not the case, and there is much more to discover as you dig deeper into the terroir of this distinctive region.