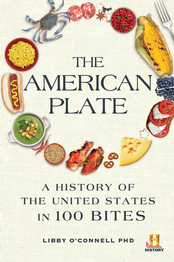

“In some respects, the past is another country…with flavors all its own that are well worth exploring,” writes Libby H. O’Connell in the introduction to The American Plate: A Culinary History in 100 Bites. In the book  O’Connell, an historian, educator and Emmy award-winning documentary producer, shares fascinating facts and entertaining insights into the transformation of our palates from the year 1400 to today.

O’Connell, an historian, educator and Emmy award-winning documentary producer, shares fascinating facts and entertaining insights into the transformation of our palates from the year 1400 to today.

More than just a history of America’s food choices and preparations, American Plate is peppered (so to speak) with recipes, including many that you might want to try yourself: Succotash, firehouse chili and shoofly pie, for example. Other recipes are offered more as a slice of history than something to whip up for tonight’s dinner (roast beaver tail anyone?). And speaking of pepper, you’ll learn a few things about this spice, beginning with Jamaican pepper (Pimenta dioica), a.k.a. allspice. “Jamaican pepper or allspice held a prominent position in early American spice cabinets, enhancing everything from hot drinks to chicken stew to puddings. Eventually its popularity waned, the way food trends, like fashion trends, come and go,“ writes O’Connell.

Allspice continues to play a starring role in holiday baking, she says, and is a key ingredient of Jamaican jerked pork and chicken. And “real” pepper? “Piper nigrum (black, white or green peppercorns, which are all from the same tree) and the Capiscum families (red peppers) are not related. Not even remotely. It was partly a marketing ploy to sell the idea of red peppers on the European continent and partly Columbus’s conviction that America was really, really part of Asia.”

But wait–did I move on too fast, failing to notice your interest perking up at the earlier mention of beaver tail? Before you rush off to check out whether Whole Foods stocks it, however, you might consider the author’s description of beaver tail as “essentially gamey-tasting fat, with swampy overtones.” Noting that Americans today “no longer consider beaver tail a desirable food,” she points out that it was a spectacularly important delicacy for two types of people in early America: American Indians, whose lean diet benefitted from “the caloric burst of an occasional beaver tail,” and hungry fur traders plying their trade in the winter wilderness.

Of course the book focuses on food rather than drink–it’s called “American Plate” not “American Glass”–but since our ancestors could clearly equal, or even best us in amount of alcohol consumed, the subject of beverages does get some attention.

Take the mint julep, that “all American mixed drink.” Along with a brief history of the julep, the author gives us a basic recipe for it so that we can enjoy this refreshing beverage whenever we want, and not just on Kentucky Derby day. But perhaps you’d prefer a glass of creamy, frothy syllabub. A British transplant to America that remained popular throughout the Revolutionary era, this drink is apparently making somewhat of a comeback today. Check out the recipe on page 69 if you think you might want to make syllabub for your next party–it’s kind of like eggnog but with wine instead of rum. “Colonial Americans found great delight in liquor-laced punch,” we’re told in the chapter on rum and whiskey. “Rum, based on sugarcane juice, provided the foundation for various punches consumed by both genders, all social classes, and a surprising number of ages. (There was no legal drinking age of eighteen or twenty-one back in those days.)”

O’Connell, who is chief historian and historic food expert at the History Channel, proves an able guide as she steers us through a whirlwind chapter on the history of American wine, from Spanish settlers planting European grapevines in Texas in the early 1600s, to the grape-growing Jesuit fathers in California in the 1700s; from Thomas Jefferson’s vineyard at Monticello to the beginning of the development of California’s wine industry in the second half of the eighteenth century. Phylloxera, the disaster of Prohibition, the 1976 triumph in Paris–American Plate hits all the historic highlights of America’s wine history. She concludes that today, “Even on the terraced hills near Jefferson’s Monticello, the wine business is thriving.”

Let me reiterate that this book’s focus is on food; it is only my own prurient interest that has prompted me to emphasize drink. But if you want to sober up after all this booziness, check out O’Connell’s chapter on coffee and tea. “We are a nation of gung-ho coffee drinkers,” she points out, and reminds us that after the Boston Tea Party in 1773 we gave up our compulsive tea drinking in favor of coffee—at least for awhile. Coffee was actually not a new taste sensation in Colonial days: “Coffee really took off in New York City, even replacing beer as the preferred breakfast drink in the early 1700s,” O’Connell explains. But when we really became a nation of devoted coffee aficionados was during the Civil War, when the U.S government issued coffee as part of their standard rations. “Coffee was warming, stimulating, and readily available, and officers found it a far better drink for enlisted men that the tot of rum or whiskey that their forefathers consumed ninety years earlier in the Revolutionary War.” When Union soldiers trouped home from the Civil War, returning veterans kept right on drinking coffee. Today, O’Connell adds, “America runs on coffee.”

Succotash:

Recipe from The American Plate

½ water

1 (10-ounce) package frozen baby lima bean, defrosted

1 (10-ounce) package fronen corn, defrosted

4-5 slices smoked duck slices

¼ cup roasted sunflower seeds

1 pinch cayenne pepper

salt to taste

Directions:

Bring the water to a boil in a large saucepan with a cover. Add the beans and corn to the pot, and reduce to simmer. Cover and cook 4-6 minutes. Drain. Meanwhile, dice and cook the smoked duck slices over low heat until crisp and all fat is rendered. Add the sunflower seeds, smoked duck crisps, and seasoning to the beans and corn. Combine well and serve.

Serves 6-8 as a side dish.

Author’s Note: If smoked duck is unavailable or too pricey, substitute 4 slices hickory-smoked bacon. I like to add 2 tablespoons olive oil, but it is more authentic to add duck or bacon fat before serving.