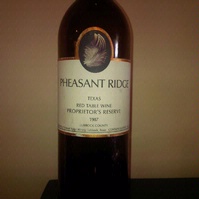

My husband and I hosted a “clean out the cellar” party last fall in preparation for a major downsize move. We warned our guests that some wines might be long past their best, but we opened some that were as good as they should be and some were delightful surprises. The Robert Mondavi Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon 1979 was glorious, still vibrant and alive. A Chateau de Jau 1997 from the Roussillon was at its peak…so  smooth and delicious. But the wine that really took my breath away was from Lubbock Texas. It was the 1987 Pheasant Ridge Proprietor’s Reserve Red made by Bobby Cox.

smooth and delicious. But the wine that really took my breath away was from Lubbock Texas. It was the 1987 Pheasant Ridge Proprietor’s Reserve Red made by Bobby Cox.

I met Bobby eons ago when I got interested in what was happening in the post-Prohibition development of the wine industry. I worked part time a couple of years for the Texas Grape Growers Association (now called Texas Wine and Grape Growers Association), and got to collaborate with the pioneers of new Texas wine like Bobby. I got the opportunity to work with Jim Hightower who was commissioner of the Texas Department of Agriculture from 1983 to 1991. Hightower was a big supporter of grape growing and winemaking as a boon to Texas agriculture. His staff organized several events in the bigger wine markets to promote the state’s wines to the wine trade. In 1984, I worked with the association and Hightower’s support to create the Lone Star State Wine Competition, now called the Lone Star International Wine Competition.

I lost touch over the years, but I did hear that Pheasant Ridge was sold in the early 1990s. Recently I read that Bobby and his wife Jennifer were again owners of the Lubbock winery. I was delighted for them and curious about how it felt to be back to the vineyard and winery that they created so many years ago.

Bobby Cox has been preaching the gospel of terroir since he began planting grapes near Lubbock, Texas in 1979. That 15-acre vineyard planted with Chenin Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc, French Colombard and Ruby Cabernet (Carignane crossed with Cabernet Sauvignon) was the largest vinifera vineyard in Texas. Over time the vineyard was expanded to 48 acres with Semillon, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc. He and his wife Jennifer along with his parents opened Pheasant Ridge Winery in 1982.

At the 1987 meeting of the Texas Grape Growers Association, Bobby gave a presentation about wine processing that he opened by saying, “One of the things winemakers in the heat of battle forget is how important the grapes are. There is absolutely no way that you can emphasize too greatly the importance of the grapes to wine quality. This is absolutely essential. Roy [a previous speaker] says 70 percent — that may not be the world’s greatest wine. Your really great wines are going to be 95 percent grapes. Those are going to be the award winners, the wines that people drink and remember and think about for a long time. That is what really a lot of us are in the business for — the romance and the significance of making some really fine wines. These kinds of wine are, like I say, in the high 90s as far as what percentage of that wine was made by the grapes.”

I wrote, “Texas: A Brief Survey from Pre-Prohibition to the Post-Oil Boom” for Chef Stephan Pyles’ (Broadway, 1993), first cookbook, New Texas Cuisine. I worked with him to develop an all American wine list for his ground breaking Routh Street Cafe featuring the Southwestern cuisine he is credited for developing. My account of Pheasant Ridge follows:

Another national acclaimed Texas winery is Pheasant Ridge, also near Lubbock. Bobby and Jennifer Cox, owners of Pheasant Ridge with Bobby’s parents, came to wine by way of their interest in food. In 1972, the couple visited the Copper Kettle in Aspen, Colorado, a renowned restaurant at that time. The visit inspired the Coxes to take home the restaurant’s cookbook and try out the recipes. They had never heard of some of the wines suggested as accompaniments to the recipes, nor were these wines easily available in Lubbock.

Bobby started working with Doc McPherson and Bob Reed [co-founders of Llano Estacado Winery] in their experimental vineyards and winery. In 1975, he and Jennifer tagged along on an equipment-buying trip to California. Bobby came back very discouraged about his ambition of owning a winery after seeing the sophisticated equipment and technology that was standard in so many California wineries. A trip to France in 1977, however, showed him that a simpler approach to winemaking was feasible. He started planning his vineyard in 1977 and bottled his first wine in 1982. (Appendix, p. 411)

In a recent conversation, Bobby said really the most important thing he learned from that trip was the concept of terroir. “My best example of terroir is from one of Peter Mayle’s books. He goes to a dry cleaner and says, ‘I have a wine stain on my shirt’ and the dry cleaner asks, ‘what kind of wine is it…a Gigondas, a Vacqueras, or a Châteauneuf-du-Pape?’ They understand that the different grapes grown in different spots are going to make a different wine stain. That’s exactly what I am talking about. We’re going to have to develop that.”

Bobby’s first job with wine was as a sommelier in a Lubbock restaurant, proving, as he said “That I was always completely insane.” He continued, “My job was to get people to drink Charles Krug Chenin Blanc instead of Mateus or Lancers or Martini or Krug Cabernet Sauvignon instead of Mouton Cadet. The Paris Judgment changed everything overnight. I couldn’t believe it.” He hoped that something like the famous 1976 blind tasting (organized by Steven Spurrier and judged by French wine experts, in which California wines were chosen over French ones) might happen for Texas wines. “But,” he said, “I finally realized that it’s not going to happen. It’s going to take work, a lot of work, wearing out your shoes going from account to account letting people know how good he grapes can be when they are grown in the right spot.”

Bobby has spent the last 20 plus years away from Pheasant Ridge working with wine grape growers to find the best grapes for the best places in to make great wine in Texas. He has encouraged growers to consider grapes that can grow in Texas’ fickle climate where if a hail or wind storm doesn’t destroy a harvest a freeze will. “My biggest grape discoveries are Trebbiano, Montepulciano and Aglianico,” he said. “Aglianico, I got that planted on a beautiful site, less fertile, a little bit rocky, on Lost Draw Vineyard in Brownfield. That’s going to be a famous vineyard someday” he said. “That little Aglianico vineyard is the largest planting of the variety in the United States.”

The Brownfield he refers to is a small town south west of Lubbock. The boom in vineyards even caught the attention of the Wall Street Journal in March of 2015. Farmers today are telling the same story I heard in the late 1970s: They are switching their crops from cotton to grape vines, because although it can easily cost $10,000 to plant a vineyard, vines require much less water and can one acre of vines can generate the same income as forty acres of cotton.”

Bobby said, “Thousands of acres have been planted. It’s a madhouse. Some will be good, some won’t. They’re trying a lot of unproven things that may work or may not. There’s 15 acres of Sagrantino. Can you think of anything crazier than that? Obviously, Tempranillo is doing extremely well and it’s very subject to the terroir. In other words, it’s very expressive. What really enjoy hearing is Hill Country winemakers talking about the difference in Tempranillo grown on the east side of Lost Draw versus on the west side. That’s where we’re going, what we’re trying to do.”

As for the job ahead, Bobby admits there’s a lot to do and he’s not the young man who created the Lubbock winery. He and Jennifer were able to acquire the name, vineyard and the winery building, but no equipment. “Obviously I’m locked into the grapes I planted 30 something years ago…Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc.” He noted that Cabernet Franc is “The vine here that makes the most interesting wine.”

He plans to replant the vineyards over the next 10 years, keeping some choice blocks of Semillon, Chenin Blanc, the old Pinot Noir block, and Cabernet. “It is still a good place to grow grapes. We were able to harvest grapes this year, and we do have old vines Chenin Blanc that’s coming out. We’re just going to go slowly expand the line and go forward.”

“We have to rebuild inventory, reestablish the brand,” he continued. Bottom line it is going to take a while. Starting over, rebooting. We’re going to be a white winery for three years while we get back on our feet. We have to figure out how much we can sell of the old inventory. Wine takes time. Still we have a good terroir. This is a good spot.” In my estimation, chances are time will prove him correct.