It was nearly 500 years ago when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortéz conquered the Aztecs and created New Spain. In 1524, as Governor of the new colony, Cortéz decreed that all colonists who received a land grant must plant grapevines. Thus, the Mexican wine industry was born. There is record of grapes being planted in the Valle de Parras of Central Mexico in 1593 and the Casa Madero Winery was established in 1597, making it the oldest winery in the northern hemisphere.

Much has changed since Cortéz’s early demand, but the intervening centuries have not been kind for Mexican wine production. Royal decrees, political upheavals and the devastation of phylloxera have all had negative impacts on vineyards. The establishment of the Pedro Domecq winery in 1972, however, marks the start of the modern wine industry in the country. Since that time, there have been many advances. Despite its large size and potential, however, Mexico ranks only 25th among the world’s wine producing nations.

The country of Mexico lies between 32 and 15 degrees of latitude. This is generally considered too low a latitude for quality wine production unless there are offsetting geographic circumstances to balance an otherwise too hot climate. Mexico’s physical setting provides these balancing factors.

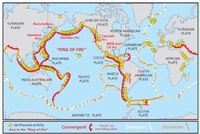

The “Ring of Fire” around the Pacific

Mexico is located in the “Ring of Fire” that surrounds the Pacific Ocean. This is one of the Earth’s most geologically active areas, with earthquake activity and volcanic eruptions on all sides. The structure of the Mexican land is a result of the earth’s tectonic plates colliding over the past 50 million years. Mexico is situated on the leading western edge of the North American Plate, whose interaction with the Pacific, Farallon, Cocos, and Caribbean plates has pushed up the land, creating high mountain ranges (Orizaba Peak, at 18,406 feet is Mexico tallest peak) as well as a high central plateau.

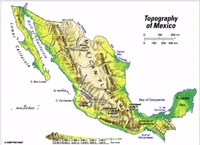

Major Topographic Regions of Mexico

Although Mexico can be divided into nine major physiographic regions, the winegrowing regions are largely in the Central Mexican Plateau and Baja California. It is the high elevation that allows Central Mexico to have potential as a winegrowing region. The average air temperature decreases about 3.3 degrees Fahrenheit per thousand feet of elevation so the Valle de Parras in Coahuila State, at nearly five thousand feet, has an average high temperature of around 90 degrees Fahrenheit and a low of around 64 degrees during July and August, the key ripening months. That’s a range similar to California’s Central Valley.

The Parras Valley is the oldest wine making region of Mexico. Similar to arid, high elevation winegrowing areas in Argentina, the Parras Valley benefits from inhibited fungal and pest problems as well as a necessary diurnal temperature shift. The Casa Madero Winery is located here and produces Chenin Blanc, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Shiraz, Merlot and Tempranillo among other varieties. Moving south to the Querétaro State, we rise in elevation to 6,000+ feet. Here, the Spanish Cava producer Freixenet has established a sparkling wine facility, using Chardonnay and Pinot Noir as well as some traditional Spanish Cava grapes in their production.

Satellite Photo of the Baja Peninsula

The Baja California peninsula in northwestern Mexico is an isolated strip of rugged and arid land extending between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California, aka the Sea of Cortez. Geologically, it is part of the Pacific Plate rather than the North American Plate. It shares a geologic heritage with coastal California west of the San Andreas Fault. This landmass is moving slowly northward relative to the North American Plate at around an inch per year on average. The Gulf of California that separates Baja from the mainland opened up only about 6 million years ago — relatively recent by geologic time standards. The central core of the peninsula is a granitic fault block with various alluvial and other sediments filling the valleys.

Vineyard on Granite Terrain in the Valle de Guadalupe

The Valle de Guadalupe is the most important winegrowing region in all of Mexico — producing 90% of the nation’s fine wine. Similar to winegrowing valleys like Santa Ynez and Santa Maria in California, the Valle de Guadalupe is influenced by the cool California Current that flows offshore in the Pacific. Heating of the inland areas during the day draws the cool marine air into the valley, providing a beneficial climate for grape growing. Baja’s vineyards have an average high temperature of around 86 degrees Fahrenheit in the ripening season. They receive most of their limited rainfall during the winter months, but are dependent on irrigation for viticulture.

Vineyards in the Valle de Guadalupe

Only a short drive south of San Diego, the Valle de Guadalupe has a burgeoning wine tourism business. The Ruta del Vino runs through the heart of wine country here and there has been significant development of hotel facilities to accommodate the increased trade in the last decade. Some of the Valle de Guadalupe producers are getting international recognition for their wines. Monte Xanic, L.A. Cetto, Vinos Pedro Domecq and Bodega de Santo Tomas all produce wines that have received accolades.

With no established winegrowing tradition, many grape varieties are planted here and unusual blends like Nebbiolo and Cabernet Sauvignon are often found. Chenin Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay are common whites, but share vineyard space with varieties like Palomino, Viognier and Muscat. While Cabernet Sauvignon is the most planted red grape, it does not dominate the vineyards as it does in the Napa Valley. We find Merlot and other Bordeaux varieties planted among Zinandel, Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Syrah and Grenache. Tempranillo, in particular, is becoming more popular in the region.

Although Mexico has around 100,000 acres of vineyard land, only about 6,000 is devoted to fine wine production. The rest is used for table grapes or as a source for distillation of Mexican brandies. The Mexican populace has a much stronger tradition of consuming beer and spirits than wine. There is an expanding middle class of consumers, especially in growing urban areas, that is now making wine their beverage of choice. The physical setting is available for increasing fine wine production. In the next decade, we may see many more Mexican wines appearing in the U.S. market.