Champagne has more than 16,000 growers, 390 houses and 125 cooperatives. Looking at the numbers you can imagine that a large percentage of the grapes are grown by people who do not make wine themselves. How might you tell if the bottle you have contains only grapes grown by a single grower versus members of a cooperative or fruit purchased and vinified by a single house? You can find a code composed of 2 letters followed by numerical digits, usually in small print on the bottom of the front label or near the winery address on the back label. The letters are the crucial part, as they are abbreviations of the ways in which Champagne producers can be legally designated. RM or Récoltant Manipulant stands for a brand which is grown and vinified by the owners, colloquially, “grower’s Champagne.” CM or Cooperative Manipulant represents a wine made by a cooperatively owned winery with multiple growers contributing fruit to the production process. There is a lesser-seen designation of RC or Récoltant Cooperateur, which is a cooperative grower who takes back must or wine from the cooperative winery to finish and market the resulting wine. Probably the most common mark to find is NM or Négociant Manipulant, which is for a winery which buys fruit, must or finished wine (and, in addition, may grow their own fruit).

Most of the bigger houses that we see in the US, Moet & Chandon, Veuve Cliquot, Taittinger, Perrier Jouet, Pol Roger etc. are NM. Which is best? As always in the world of wine, it depends. The RM or grower wines offer unique expressions, featuring grapes from a more specific area of Champagne as well as highlighting a distinct house style that may be less commercially focused. Cooperatively produced wines can offer a sharp pricing. While the large house Champagnes span a range of style but most importantly offer technical excellence, consistency and availability. Master of Wine Jancis Robinson has said, “I am a huge fan of some of the best of the Champagne growers’ wines, and I also believe they can offer much better value than many of the wines offered by the big houses which have such substantial teams, plant and marketing budgets to sustain.” Note that Grower and cooperatively made wine only account for about 8% of exports.

Perhaps a better value in French sparkling wines are wines labeled under the code word, “Crémant.” There are 8 regions allowed to make these wines from local grapes with the regional name included, e.g. Crémant de Bourgogne, for wines from Burgundy. They all follow a similarly stringent set of rules; grapes must be hand harvested, maximum pressing yield of 100 HL of juice per 150 Kg of grapes, must be fermented in barrel and then undergo a second fermentation in bottle. The resulting wine must be aged for a minimum of 9 months on lees in bottle. Finally, the bottles must be disgorged (yeast removed after aging). This follows the same basic production methods as the better-known Champagne region. Each of the eight regions make wine based on their own local varieties (including minor gapes not listed here) as follows:

Italy makes sparkling wines across nearly the whole country, in a range of styles and using different methods and Prosecco is probably the best-known by many readers. Wines are based on the local Glera grape and use the Martinotti or bulk method of secondary fermentation to attain their characteristic sparkle. The name of the region dates back to the mid 1700s, it was delimited on maps in the 1930, became a DOC in 1969 and a portion became a DOCG in 2009. DOC stands for Denominazione di Origine Controllata and controls both the physical limits of the region where the grapes may be grown as well as basics such as allowed grape varieties, yields and production methods.

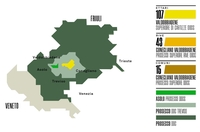

The secret code here will give you a better idea of the geographic specificity of the bottling and can usually be found on a uniquely numbered strip of colored paper often applied to the foil of the bottle. The most basic wines are bottled simply as Prosecco DOC. The next more specific growing region uses the Prosecco DOC Treviso designation. Asolo DOCG, granted in 2009, is a separate and unique growing area featuring steep vineyards and a relatively cooler mesoclimate, within the larger Prosecco zone and is located about an hour north of Venice. The addition of the G is important, it stands for e Garantita. In addition to following more stringent production rules, the wines are tested for technical analysis and were historically tasted for typicity. Finally, we get to the heart of the historic Prosecco production area, located east of Asolo and located in the vicinities of the cities of Conegliano and Valdobbiadene. This regional designation has three different DOCG each from a smaller and more unique area; Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore DOCG (the addition of Superiore designates a wine which has naturally attained a higher degree of ripeness in the grapes at harvest), Conegliano Valdobbiadene Rive Superiore DOCG, which comes from one of 43 specific vineyards or communes which will be listed on the label and which requires a vintage, e.g., Valdobbiadene Rive di Soligo. Finally, Conegliano Valdobbiadene di Cartizze DOGC, a zone made up of just 107 hectares which has been recognized since 1969. Each of the correspondingly smaller areas requires a lower yield per hectare of vineyards. This regional specificity matters not just due to the more specific wines commanding higher prices, nor simply due to history or incline of the vineyards, but also as to soil differences as seen below. Each of these different soils yield grapes with subtly different flavors. Below you’ll see Prosecco soils, with images from top to bottom depicting the Central Zone, Cartizze DOCG, and Eastern Zone:

Lambrusco may only be the butt of jokes for ’70s and ’80s kids who may remember TV commercials from the 80’s proclaiming, “Riunite on ice…so nice.” In my day-to-day work in a wine shop, I’ve seen that current drinkers enjoy this classic, pale pink to deep ruby colored sparkling wine quite a bit. There are four major regions producing Lambrusco wines, located in Emilia Romagna and around the city of Modena. They all use autochthonous grapes which vary in color intensity. Most importantly in terms of a match for the table, the modern wines are drier than their predecessors, though they range in levels of sweetness. The secret code to understand sweetness levels has two parts; the first a term such as Brut/Secco (dry) Semisecco/Amabile (the latter literally “friendly,” meaning off-dry) or Dolce (sweet); the second is to look at alcohol levels, with higher levels corresponding to drier wines.

Moving onto the other major sparkling wine producer in Europe, Spain, let’s explore the wide range of wines being made. Here there are both marks on corks as well as minimum aging, which is called out on strip labels for the traditional method Cava and the newer Corpinnat wines. Sparkling wines can be made in a number of ways, but there are four that have unique symbols you can see marked on corks of Spanish sparklers. A triangle signifies a carbonated wine (think soda pop), while a hollow circle represents a wine which was fermented in a tank to obtain its sparkle. A rectangle represents a wine which was fermented in its individual bottle from outside one of the delimited Cava production zones with only a short period of aging on the yeast. Finally, a four-pointed star is the symbol you will find on bottles of Cava, which are produced using traditional methods, second fermentation in bottle and aging on the lees in the bottle for the minimum time of 9 months. In addition to these symbols, you can often find an RE (Registro de Envasadores de Vinos), or winery registration number on the cork, two letters followed by a number. While perhaps not important it is interesting that you can verify the province of production, where BA stands for Barcelona and VA Valencia, for example.

While I’m writing about traditional method wines from Spain it is worth explaining more about the changes happening in the world of Cava, where a number of high-quality producers have left the DO or Denominacion de Origin. The growers who left often exceeded the quality parameters of basic Cava, using reduced vineyard yields, organic and biodynamic farming practices, hand harvesting, and aging wines 3-4 times as long as the minimums. In 2012 Raventos y Blanc, following the lead of 22nd generation winegrower Pepe Raventos, established a unique DO called Conca del Riu Anoia, encompassing the valley where his family has been growing grapes since 1497. This was followed in 2017 by 6 growers establishing Corpinnat, its own unique, cooperative marketing brand which requires organic farming methods, hand harvesting of fruit and estate production (growing the grapes and producing the wines on the estate premises), followed by extended aging of the wines on their lees, including 3 minimum aging lengths, 18 months (twice as long a the minimum for Cava), 30 months and 60 months.

In response the Cava DO have updated their designations in 2020, offering 4 certified aging levels, Cava de Guarda (9 months minimum) and Cava de Guarda Superior with 3 sub-designations; Reserva (18 months), Gran Reserva (30 months), and a new Cava de Paraje Calificado, which requires a unique site and 36 months aging. For the upper three designations, there are a number of other requirements including traceability from grape to glass, organic farming, vintage dating and maximum yields per hectare (much more strict than most competitive wines). There is also a designation called Elaborador Integral, for wineries which press and vinify exclusively on their estates (note no word on where fruit comes from). Finally, they have created a hierarchy of geography as well, which should help clarify origins for consumers. There is basic Cava DO, then 4 separate regions; Comtats de Barcelona (with 5 more specific subregions); Valle de Ebro (with 2 more specific subregions around Lorgoño and in the province Aragon); Valle de Almendralejo in Extremadura and finally Requena, Levante or Valencia inland from the city of Valencia (final name TBD). While the new rules are quite stringent and may even seem to mimic the basics of Corppinat, they are also quite impenetrable with a lot of variables, even for a seasoned wine industry vet and self-proclaimed wine geek like me.

European Sparkling Wines by the Numbers

Yields and Allowed Harvest Methods:

Most of these regions are highly regulated, including the number of vines per hectare, training methods, pruning rules, yield per plant and vineyard area as well as liquid/juice yield per mass of fruit pressed. Yields listed below represent the mass of grapes per area of vineyard land. Each of the regions also regulates the maximum volume of liquid grape juice which may be pressed from a mass of grapes ranging from 63.5% in Champagne to 70% for Prosecco.

—Champagne: The yields allowed for the harvest are not fixed and vary every year, but should comply with EU regulations of a maximum of 15.5 tons/hectare. The Comite’s website claims a limit of around 11.4 tons/hectare. Grapes must be hand harvested.

—Crémant: The yields vary by region from 13 to 16 tons/hectare, depending on both the region as well as the vine density and training method of the vine. Grapes must be harvested by hand.

—Prosecco: DOCG 13.5 tons/hectare, Rive 13 , Cartizze 12. Machine harvesting allowed.

Machine harvesting allowed only for Cavas de Guards, higher level mandate hand harvesting.

—Corpinnat: 12 tons per hectare, however if the grapes have been irrigated, the limit is reduced to 8 tons per hectare[!]. Grapes must be harvested by hand.

Sugar:

All these wines can contain some sugar, when allowed, added at the time of bottling. The amount of sugar left in the bottle can range from nearly zero up to 5%, and is usually listed as grams per liter. As these wines often have relatively high levels of acidity, and because of acidity’s sensory effect in balancing sweetness, sugar levels in the lower-middle of this range will taste “dry” to most wine drinkers. Please consider that this range is equivalent to around 1.5 teaspoons per bottle, not much compared to the amount most people consume in their caffeinated or carbonated beverage of choice. From driest to sweetest they run as indicated below, with the coding being F = French term; I = Italian, and S= Spanish:

—Brut Nature (all) / Brut Zero (F) – no added sugar and <3 grams/liter residual

—Extra Brut (all) – 0-6 grams/liter

—Brut (all) – maximum of 12 g/l, or 1.2%

—Extra Dry (F/I) / Extra Seco (S) – 12-17 g/l

—Dry (F, I) / Seco (S) – 17-32 g/l

—Demi-Sec (F, I) / Semi-Seco (S) – 32-50 g/l

—Doux (F) / Dolce (I) / Dulce (S) – 50+ g/l

—While I could not find any values or limits for Lambrusco wines, the produce 4 styles listed from driest to sweetest as Secco, Semisecco, Amabile and Dolce.

Pressures:

The pressures in a finished bottle of sparkling wine vary fairly widely. Wines with higher pressure levels will show more energetic mousse in the glass and have a sharper texture and drier sensation on the tongue. Lower pressure relates to softer textures, sometimes described as creamy. Note that one bar of pressure is just below average atmospheric pressure at sea level, around 14.7 psi.

—Champagne 6 bars, though Mumm bottles a Blanc de Blanc at a claimed 4.5 and I’ve seen reference to RM producers using lower pressures as well.

—Crémant requires 4 Bars, Crémant de Bourgogne claims 6 bars

—Prosecco: 3 bars, A less gassy version called Frizzante 1.5-2.5 bars

I could not find numbers for Lambrusco, Cava or Corppinat. Given that Lambrusco is made using bulk/Martinotti/Charmat method, I assume a similar 2-3 bars. Cava and Corpinnat follow traditional methods, and so should have around 6 atmospheres of pressure.

Special thanks to Joaquin Galvez, Chileno/Spanish winemaker and host of Wineman, a road show (in Spanish) about the culture and practice of wine available on Tubi here: https://tubitv.com/series/300002042/wineman for his assistance with tracking down info about the codes on Spanish sparkling wine corks.

For further reading on the amazing variety of aromas possible in sparkling wines, visit the Comite de Champagne aroma chart (https://www.champagne.fr/sites/default/files/2022-11/Carte_Des_Aromes_EN.pdf) or an even deeper dive on Cava aromas and food ingredient matching via renowned Sommelier Francois Chartier on the DO Cava site (https://www.cava.wine/en/discover/molecular-study-cava/)