Yes, the world is full of political problems from Ukraine to Syria and across central Africa, and yes, everybody wishes that economic growth was more robust than it is. Still, it is always difficult to assess the present without the benefit of hindsight, and there’s a strong chance that we’re failing to appreciate some current realities precisely because of our economic and political problems. Here’s one to consider: There has never, ever, been such a great time to buy wine. For this we can thank a sustained period of price softening coupled with continuing improvements in production quality, plus a strong dollar and important developments enabling us to buy wines in a commercial environment that is more transparent and competitive than ever before.

Of course this is especially true if you’ve got a decent sum of money to spend on wine, but even if you’ve barely got any, this is still the best time ever.

To be clear, my assertion is limited to the current situation for consumers, because there have definitely been better times to be a wine producer, or to sell wine as an importer, distributor, restaurateur or retailer. Take for instance the late 1990s. But if you are a consumer, there’s never been a period that measures up to the present. Consider the following handful of factors:

1) Massive Price Softening: Decades of overly-enthusiastic planting and winery construction that began in the mid-1980s slammed into the wall of a deep recession in 2008. The recession, as we know all too well, was not only unusually deep and protracted but also extremely broad–it affected nearly everyone. As a result, almost everybody felt notably poorer. And for good reason: Almost everybody really became notably poorer.

This produced some interesting–and revealing–results in the economics of wine commerce. Without getting all technical on you, I need to trot out a couple of concepts to explain what happened, which was not a simple excess of supply relative to demand.

The recession showed that wine holds a high degree of “demand inelasticity” as a commodity, which is to say that people who love it won’t stop buying it even if they’ve got less money to spend. Conversely, however, wine demand showed an extremely high level of “price elasticity,” which is to say that devoted wine lovers will show virtually no devotion to wine at a particular price level when they’ve got less to spend.

Love of wine turned out to be both constant and fickle. Wine lovers remained faithful to wine in general, but, to be blunt, they dumped $100+ per bottle Napa Cabernets faster than a cheerleader drops an 8th grade boy with a raging acne breakout. “Cult” wines that had always sold out within weeks (with hundreds of would-be consumers languishing on waiting lists and never getting a chance to buy them at all) started appearing on close-out Web sites. Some famous wines continue to be discounted almost immediately after being released. It would be rude of me to identify any wine in particular as an example, so I won’t mention the fact that I now routinely see Joseph Phelps “Insignia” discounted on the Wines ‘Till Sold Out site.

Moreover, and very importantly, the recession was so deep, broad and protracted that consumers turned their backs on almost everything at the prices they had formerly been prepared to pay–not just super expensive wines. You can now get amazing deals on Napa Cabs or cru Barolos that you formerly couldn’t even find, but likewise you can buy Marlborough Sauvignon Blancs or simple Rioja Crianzas for half the price you’d have paid eight years ago.

There are exceptions, to be sure, but then there are always exceptions when it comes to wine. For example, very rare, high-end wines like Lafite Rothschild and Romanee-Conti never dropped much in price (though older vintages suddenly became available at prices no higher than current releases; more on this below). It is also true that a few less expensive wine types (like Malbec from Argentina) held stable in terms of price because consumers who formerly bought more expensive wines flocked to them in droves. But these exceptions don’t invalidate the rule: Prices are incredibly soft today when considered in historical terms, and this good news is made even better by the facts that quality hasn’t dropped and that consumers can now find their way to bargains much more effectively than ever before.

2) Quality Continues to Rise Even as Prices Remain Soft: We can understand this phenomenon by starting with the same observation we made above, namely, overly-enthusiastic planting and winery construction began in the mid-1980s and continued for more than two decades all over the world. This produced an intensely competitive environment in the mid-2000s that became even more competitive when consumers suddenly felt the floor fall out from beneath them in 2008. The situation confronted almost all producers everywhere with a stark imperative: Make concessions on price, or find new buyers trading down from more expensive wines, or you’ll go belly-up. And moreover: Maintain or boost quality by restricting crop yields and employing leading-edge talent and technology–or a competitor will eat your lunch.

Those who follow the news in the wine trade know that a lot of bellies turned up and a lot of lunches got eaten during the past four years. I do not mean to make light of this: Lots of good people lost their jobs or lost their wineries during the past eight years, and not just because they were inflexible on price or insensitive to the need to innovate. It is a cruel reality that a rising tide raises all boats, but an economic downdraft blows away some ships that should survive while sparing others that seem less worthy.

Be that as it may, this is a column about a Golden Age for consumers rather than the wine trade, and consumers continue to benefit from the fact that almost every winery that remains afloat today knows that if it slacks off for even one vintage it may run aground for good.

I’ll cut with the nautical metaphors to conclude this section by answering a question you might be asking: How do you, Franz, know that quality is rising? By tasting a boatload of wine. To be specific, I’ve tasted between 8,000 and 10,000 wines in each of the past eight years, and have judged at least five international wine competitions while also logging between 50,000 and 90,000 air miles per year to visit wine regions. And I’m here to tell you that quality has never been so high. At all price levels. Great wine is greater than ever, and cheap wine is way, way better than ever.

If you think that point scores are rising only because critics are engaging in something akin to grade inflation, I’d understand your suspicion but tell you that there’s more going on than just that. I acknowledge that there are some fields in human life in which there’s no genuine progress (like politics), but insist that there are others (like sports) in which performances are manifestly better with each passing period. Wine is way more like sports than politics in this regard, and if you don’t believe me, grab your corkscrew and put my assertion to the test.

3) Misfortune for Some is a Boon for The Many: This sounds cold, I know. But again, I’m not focused on the trade or particular individuals, but rather the general situation for wine consumers. Many people who over-bought expensive wines have been shedding them since 2008, selling them to retailers who are throwing superb, mature wines back onto the market–often at eye-popping prices. Eight years ago, it was relatively rare for retailers to sell wines they purchased from private cellars. Today, it has become a big business, and a business that has changed the commercial environment for newly-released wines almost as much as for aged bottles.

In addition to wines that were once in private cellars, the current market is also flush with wines that got stuck in the wine trade’s pipeline after things went sour in 2008.

Wines from either of these sources can offer amazing opportunities in their own right while also keeping prices down for new releases. Why, for example, would anybody shell out big bucks for vintage port from 2011 and need to age it for 30 years when they could buy vintage ports of equivalent quality–that are much closer to maturity–for virtually the same price? As I’m writing this, the average price on winesearcher.com for the standard-setting Taylor Fladgate Vintage Port is $100 for the 2011, whereas you can get the 2003 (with equivalent or higher critic scores) for $105. I’m sorry, but anyone who wouldn’t prefer the 2003 doesn’t understand vintage port, or mistakenly believes that they’ll live forever. One more thing: Why is the low price for the 2011 still at $82, barely having budged from its initial release price? Because the low price in the USA for that 2003 is $70.

This resale phenomenon has been accelerated by a new sensibility regarding consumption that has settled on Western societies since 2008. There’s no question that conspicuous consumption has declined in favor of more modest purchasing, and of course this has affected restaurants. Many of them piled up amazing collections of wines during the boom years, taking in all of the highly-allocated items they were offered on the assumption that they’d be able to sell Opus One to Fat Cats forever. As the failure of that strategy has become increasingly apparent, restaurants have added momentum to the sell-off from private cellars.

Admittedly, most of the wines being dumped onto the market are high-end bottles that can only be purchased by reasonably affluent buyers. However, almost anyone who knows wine pretty well and who has a little to spend can benefit from the current climate. This is because of a cascading effect: 2003 Taylor Fladgate is not only holding down prices for 2011 Taylor Fladgate, but also holding down prices for 2nd tier vintage ports like Warre’s, which is in turn holding down prices for the single quinta ports from 2008, which are helping to hold down the whole port category, including fairly affordable products like LBVs and 10-year aged tawnies.

This cascading effect can be found in many wine types–not just port. For example, if you want to understand the amazingly low prices being asked for Barolo and Barbaresco from the terrific 2010 vintage, just take a look (on WineSearcher or WineZap or WineBid) at how many top wines can be had at comparable prices from the equally terrific vintages of 2004 and 2008. For example, I purchased the totally sensational Virna Borgogno Barolo Preda Sarmassa 2008 for two weeks ago for $29, with free shipping and no sales tax. I almost felt guilty about the transaction, but I got over it. This is the new reality, and it won’t last forever, and every wine lover should consider taking advantage of it.

4) A Strong Dollar and a Notably Strengthened Economy: This factor doesn’t require extended explanation–much less argumentation–because it boils down to simple arithmetic. On July 15, 2008, it took 1.60 U.S. Dollars to buy a single Euro, whereas it takes only 1.12 to buy one today. Translated into wine terms, a bottle of Bordeaux that sold for 75 Euros cost $120 in 2008, whereas it would cost you $84 today.

That is a big deal, as you can plainly see, and it is a big deal with ripple effects. As we saw above, the presence of mature wines on the market is holding down prices for current releases, but the reverse is also true: The dollar is now so strong against the Euro (and Argentina’s Peso and South Africa’s Rand) that new imports are keeping old wines stuck in the pipeline, as well as ones purchased three years ago when the dollar was much weaker. All three of these wine types are competing against one another for consumer attention, and the result is that prices must remain moderate for all three types–or they simply won’t sell.

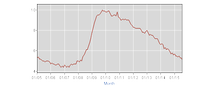

Of course, none of this does a consumer any good if he or she can’t afford to buy wine under these advantageous conditions. However, the fact is that purchasing power is now increasing much more rapidly than wine prices are rising. Two days ago, economic growth in the USA during the second quarter of 2015 was revised up to 3.7% from an initial projection of 2.3%, and 3.7% is a very impressive number if not exactly a boom. Moreover, unemployment in the USA has been cut in half during the past six years, falling from 10% in October of 2009 to 5.1% in August of 2015. The longer-term trends are equally telling, and here a picture is worth a thousand words:

That graph showing unemployment in the USA from 2005 – 2015 is derived from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics. Although almost everyone agrees that income inequality remains a problem and that many recently-created jobs are at lower wage levels than would be optimal, purchasing power, consumer confidence and housing prices have all risen markedly in the past few years, and the overall condition of the economy has improved very significantly by almost every available measure. At the risk of repeating myself, one reason for characterizing the current situation as a Golden Age for wine buyers is this: Purchasing power is now increasing much more rapidly than wine prices are rising.

5) The Rise of Direct Shipping in the Age of Transparency: Each of the four factors addressed to this point has been heightened by this fifth one, which is being fed by two distinct but related tributaries. A decade ago, consumers in relatively few states could buy wine directly from purveyors, but today the situation has flip-flopped. The most aggressive retailers are now shipping to many more states than those from which they still shy away. Add to this the rise of wine search websites and here’s what arises: Most consumers in most states can access the inventories of most retailers anywhere in the country, pit the purveyors against one another, and get wines from the low bidder shipped to them. And as icing on the cake, buying from out of state usually eliminates sales tax, a savings that will more than cover the cost of shipping in many instances.

If you don’t think that this development is a big deal, you haven’t yet sized it up. It is not hyperbole to describe the phenomenon in terms like, “game changing” or even “revolutionary.” It tilts the retail playing field massively in favor of the consumer, enabling a wine lover to move beyond the few wine shops in his or her area and bring hundreds of them into play in a competitive situation marked by nearly perfect transparency.

Every time a shopper is lured by a special offer (whether in an advertisement or on a store display), it is now possible to scrutinize exactly how “special” it actually is–with just a few keystrokes on a computer or, better still, a quick glance at a smart phone while on the floor of a retail shop.

This situation is fundamentally new, and naturally there are some who dislike it. Predictably enough, the detractors of wine search websites are usually those whose profit margins are imperiled by them. That group includes retailers, of course, but I’ve also heard wine producers complain that the combination of search sites and direct shipping makes it unduly difficult for them to maintain favorable price levels for their wines.

Then there’s the objection that the relationship between the consumer and the retail wine consultant has been badly undermined. This is undoubtedly true to some extent, though one can wonder how much we should really bemoan this. If all sales consultants were well informed and consistently motivated to sell only excellent wines at minimal markups, the new situation would appear to have a serious downside. But that isn’t the case, as everyone knows.

I’m aware that I’m raising a controversial point here, but one can argue that wine critics taste a lot more wine than consultants, and offer better advice to consumers with less conflict of interest. As for getting a fair price for the wine that you buy, it seems to me that your odds are a lot better if you rely on a wine search website than on the pricing restraint of a local retailer.

In the last analysis, if you wish to remain loyal to your favorite retailer, wine search websites won’t prevent you from doing that–though they will tell you exactly how much your loyalty is costing you. It is worth noting that the websites survive because retailers pay to have their inventories appear on them, so any wounds to the retail sector are largely self-inflicted ones. The new situation is one marked by much more intense competition among sellers based on much better information for consumers. That sounds to me like a change for the better when judged in the light of free enterprise principles, and there’s no doubt that it is a colossal improvement for consumers.

Summing up, there is a historically unprecedented abundance of great wine at moderate prices available right now. At lower price levels, there’s no question that quality is the highest that it has ever been, and circumstances for budget-conscious consumers have likewise never been better. Nobody can say when things may take a turn for the worse, but it is quite clear that all of us who love wine should relish this era for as long as it lasts.

Questions or comments? Write to me at [email protected]