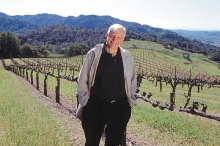

When you visit kj.com, the home page of Kendall-Jackson, there is a picture of its patriarch and owner, Jess Jackson, leg up on a pile of attractive rubble in one of his vineyards. Beneath the pile of rock a single word appears: Truth. It’s not clear if this is meant to be a motto, a promise, a projection, or a character-defining trait, but the association and the positioning are pretty unmistakable.

I have never met a winery owner who relishes competition more than Jess Jackson. Most owners are genial men (and nearly all of them are men) who got into the wine business having made a sizable fortune in some other enterprise, and approached the wine industry as a second career out of a love for wine, and the allure of the lifestyle that went with it.

But while Jackson is in every respect a gentleman, his role in the industry is far more calculating than most of his peers and, in the end, he has triumphed, displaying a fierce competitiveness that is by turns brilliant, high-minded, canny, aggressive, opportunistic, and controversial.

He has transformed the industry at least twice, and in the last ten years has emerged as one of California’s most envied property owners, one of its most dedicated stewards, and by far one of its richest men.

He has transformed the industry at least twice, and in the last ten years has emerged as one of California’s most envied property owners, one of its most dedicated stewards, and by far one of its richest men.

He has trimmed his presence in the value tier he more or less invented, and has acquired some of California’s most prized vineyard land as well as more than a dozen of its most storied and highly regarded wineries, including Cardinale, Lokoya, Matanzas Creek, Arrowood and La Crema. More than any other figure at this moment, Jess Jackson is the master of the American wine market — and when you’re in that position, maybe even Truth lies within your sphere of influence.

Last week Jackson hosted a trade event called Vinsight, inviting some of California’s most respected sommeliers to a tasting that pitted the top wines from his top wineries against some of the most prestigious wines of France, California, Oregon, and Washington.

The lineup of 39 wines included selections from estates like Petrus, Latour, and Harlan, as well as properties like Echezeaux, Clos Vougeot, and Batard-Montrachet. Joining Jackson on the dais was moderator Ronn Wiegand, one of a handful of wine professionals in the world who holds both a Master of Wine and a Master Sommelier credential. Before us were thirteen flights of three, which we were to taste and rank. The tasting was conducted blind, except for varietal.

Jackson’s stated purpose was to reintroduce those present to some of the world’s most prestigious, highly regarded wines in the world. His other purpose, of course, was to place his wines in their company, which he premised by asserting that wines from the Old and New World have begun to converge in terms of style, variety and terroir expression.

‘No longer do the standard definitions of Old and New World, or ‘elegant’ and ‘big’ apply,’ he wrote in a preamble to the tasting booklet. ‘The very notion of regionality itself has become blurred and the wine truisms we once held to be gospel have been shaken by many factors.’

One of those factors, of course, is Jackson himself. Jackson transformed the wine industry by blending chardonnay fruit from different regions to produce a high-quality, easy-to-drink white that soared above jug wine in quality and yet was much less expensive than the premium bottlings of the era.

As Paul Lukacs writes in American Vintage, his engaging chronicle of the American wine industry, Jackson was ‘Chardonnay’s chief American popularizer.’ Lukacs quotes Jackson as saying ‘There was a hole in the market I could drive a truck through.’

He did this with a wine that was as irresistible as it was formulaic, a vintage wine that did away with vintage variation, that succeeded in providing quality with consistency, a thing that American wine had never actually delivered at such an attractive price.

There was nothing gentlemanly about this approach, and it had little to do with farming or terroir. But Jackson’s great innovations of the eighties and nineties were driven primarily by shrewd market analysis and a mastery of quality for price that continues to this day in the many tiers that now bear the Kendall-Jackson name. As Lukacs writes, ‘Jackson and Steele (Jed Steele, his then-winemaker) never tried to express a taste of place. Instead, they made wines to fit the stylistic profile they had defined.’

And in doing so, they redefined California wine.

With his dynasty in place, Jackson has recast his message dramatically from disdaining terroir expression to embracing it. He has converted nearly his entire production to estate wines, giving him unprecedented control on farming and fruit quality, and to his credit, has committed to environmentally conscious, sustainable growing practices — some 14,000 vineyard acres.

His water management practices alone should serve as an industry standard. He has made stewardship and responsible land management a long-term tenet of his vineyard practices. That, along with many other things, will contribute to his legacy.

Meanwhile, Jackson is being retooled as the gentleman farmer he never got to be. Page through an upscale magazine to a Kendall-Jackson advertisement, and you’ll notice they’re no longer advertising wine, they’re advertising him. After conquering the industry, Jackson is being positioned as a steward, a patron, a patriarch. Papa Jackson is the new brand, as the weathered visage beneath the brim of a sweat-stained hat, his well-worn boots at the door, dusted with Mother Earth.

All of this makes it hard to sit down to a table of 39 wines and not be wary that a bit of truthiness may have been blended in with all the truth. Quite apart from the various subtexts discussed so far, a tasting of such high-end wines brings with it a fair amount of anxiety.

There is, for example, the hard fact of learning that you disliked a wine you thought you loved; it’s almost as unnerving as disliking a wine you’re supposed to love, which is how I felt about an especially taciturn 2004 Bonnes-Mares from Comte George de Vogüé.

There is also the mild embarrassment at having been seduced by a wine you didn’t really want to like, as in the inky, Syrah-like Pinot Noir from Kosta Browne.

It goes without saying that a Kendall-Jackson or Artisans and Estates wine was in every flight. Inevitably, the wines were part of each conversation — all of them, regardless of their performance, were elevated by association. This was one of the few times I have ever had the pleasure of tasting Petrus, for example. It is probably the last time I’ll taste it alongside Verité, ‘La Muse.’

Wiegand handled the conversations well enough, but there were a few occasions when his enthusiasm seemed a little too calculated toward pleasing the man sitting next to him. It probably wasn’t necessary, for example, to go out of his way to praise the Vintner’s Reserve chardonnay, despite the fact that the wine was ranked last in its flight, or emphasize the stratospheric prices of the Bordeaux on the table, which inevitably improved the stature of the more reasonably priced wines from the Jackson stable.

There was, in short, more than a bit of handling beyond the glass. Sometimes it was subtle; sometimes it was so obvious you could drive a truck through it.

In six of the thirteen flights, the Jackson wine was ranked third of three, meaning it took first or second best in a majority of flights. Despite the fact that Jackson and his team controlled every variable, the showing was impressive, especially given the competition. Moreover, by my reckoning three of the wines were out-and-out superb: Lokoya’s 2004 Mt. Veeder Cabernet, the 2004 Cardinale, the 2005 Land’s Edge Pinot Noir from Hartford Court.

So where did it leave us? Did the tasting confirm Jackson’s assertion that the world’s wines were experiencing an historic convergence? Did Jackson’s wines hold their own, or were the results self-fulfilling at best?

At a reception after the event, sommeliers congratulated themselves on their perspicacity, enhanced by the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, while K-J staffers milled about somewhat nervously, trying to gauge the mood. Jackson, meanwhile, mingled with the crowd, sipping Champagne, beaming, ebullient. At 77, at the top of his game, he didn’t have to care about the results, and yet it was clear the experience had gotten his competitive juices flowing, and his confidence was never higher.

His is still a family winery, as he takes great pains to point out. But it’s sort of like calling Starbucks a coffee shop; at bottom that characterization is a euphemism, unless he’s willing to admit that his family has more in common with the Rockefellers and the Carnegies than with mine.

In the end, the tasting existed in a similar, strangely fuzzy reality, carefully crafted by a man who clearly wants the world to acknowledge the greatness of his portfolio, even if it means placing us squarely within his sphere of influence to have us believe it.