Even though I live on the East Coast, and even though the first vineyard I worked in was planted to Chambourcin and Seyval Blanc, 99.9% of my wine drinking and wine writing through the years have involved wines made solely from vinifera grapes. At the same time, the remaining one-tenth – French-American hybrids – has on occasion offered interesting results.

These exceptions have come from years of tasting, buying and on occasion cellaring French hybrid wines made by local Pennsylvania winemakers who find the hybrids better suited to their cold winters and humid summers. Most of these hybrid wines have been enjoyable and well-structured, though not on a par with “Old World” standard varieties.  That’s because, tasted fresh, hybrids, especially the reds, usually retain a bit of that foxy, grape-juicy characteristics as well as a papery undertaste coming from the native American grape component of the equation.

That’s because, tasted fresh, hybrids, especially the reds, usually retain a bit of that foxy, grape-juicy characteristics as well as a papery undertaste coming from the native American grape component of the equation.

None of this surprises me, as I think grape variety, for good or bad, is the most important part of the winemaking trinity of Soil, Grape and Winemaker. The grape is only capable of producing the aromas and flavors that its DNA will allow. Soil will be simpatico with some grape varieties more than other. The winemaker, or at least those who are in control of their vineyards, can wrestle with these two components to come up with the juice and skins that she or he thinks can make the best wine possible (or most-profitable).

So it is with Chambourcin. Vidal Blanc and Seyval Blanc make interesting hybrid whites and sparkling wines, and Chambourcin seems to win out as a favorite red among winegrowers, with perhaps Foch coming in second.

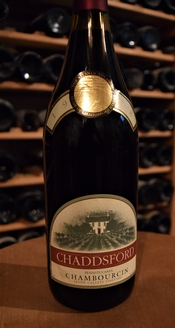

During the years that Eric Miller was winemaker, co-owner and co-founder (with his wife Lee) of Chaddsford Winery in the Brandywine Valley of Pennsylvania – roughly from 1982 to 2013 – he made varietal Chambourcins along with vinifera standouts such as Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, largely from grapes sourced regionally. But, while enjoyable and easy drinking, the Chambourcins still retained some of the foxy characteristics, even when lightly chilled.

Nevertheless, I would buy a case or half case of most vintages of the Chambourcin, along with the vinifera wines, telling myself they would be good weekday wines and great for barbecues. However, during the 1990s I was re-building a depleted home cellar, so much of my drinking was of new bottles that might warrant a case. Many of the Chaddsford Chambourcins lay fallow in my basement.

When I again started writing about wines regularly at the turn of the current century, I quit collecting because wine samples began trickling in—and then pouring in. So, except for trophy bottles pulled when we were entertaining, the rest of my collection, mostly everyday wines, was largely neglected. Then, about five years ago, I realized I had to start drinking, or at least tasting, these older bottles or they would all turn bad.

Surprisingly, most hadn’t. Even the 30- to 40-year-olds were mostly sound, which really didn’t surprise me. First, I always purchased wines for my cellar that were well-balanced with good fruit and acidity, and I expected them to age as well as older bottles of Bordeaux, Burgundies, Rhônes and Riojas that winegrowers would pour during my press trips to Europe. Second, I am fortunate that both my wife and I enjoy older wines as well as, to quote Steve Martin in The Jerk, “fresh wines.”

So, I was pleased, though not surprised, to find that Miller’s Chaddsford’s Pinot Noirs were holding well and drinking well. The Chambourcins? We mostly ignored them, not expecting much. I opened one or two and in passing noted, “not too bad.” Then recently I opened a 1998 Chaddsford Chambourcin – 25 years old – and seriously paid attention. The ullage was good, and the cork sound (although cautiously extracted with an Ah So opener).

The wine was not in the least oxidized in taste or color, was full-bodied with ripe and still vibrant berry flavors, rich and long on the palate, still good structure with no tart acidity and with barely noticeable tannins. Not a great wine, but certainly a very, very good one that guests would marvel at both for its taste and age.

But the interesting thing is – and I had noticed this with earlier bottles – that foxy, papery hybrid taste had disappeared with aging. I had previously experienced a similar varietal “changeling” with Gamay on those occasions when a Beaune négociant pulled out an older bottle of cru Beaujolais to taste with the Côtes d’Or and Chalonnaise Pinots. Having spent several years in the bottle, the varietal characteristics of the Gamays were almost the same as the older Pinots and could even be confused as an old Pinot.

In this case, the Chambourcin did not taste like an older Pinot or Cabernet, but was very similar to an aged Grenache in its fruitiness and mellow nature. Apparently, something in the slow oxidation and aging process allows this to happen, all within the grape’s DNA limitations.

Recently, I was at a tasting hosted by Eric Miller of wine geeks and professionals who were comparing recent vintages of Burgundy and Oregon Pinot Noirs. I took along one of the Chaddsford Pinots from the late ‘90s, and even he was surprised at how well it was tasting. The contents of the bottle quickly disappeared. When I mentioned my experience with his Chambourcin and the apparent age-ability of that grape, Miller smiled and said, “Ah, but the winemaker has to know how to make the Chambourcin so that it is capable of aging.”

Hopefully, other talented and serious winemakers in the Eastern U.S. who produce varietal Chambourcins – and their wine fans who buy the bottles – will give a few of those wines a chance to age 10 to 20 years.

(Here, I had planned to end the blog, but there is a P.S.:)

Yesterday, I searched deeper into the cellar dust and unearthed a bottle of the first vintage of Chaddsford Chambourcin, a 1982 Reserve – 41 years old. It did not look too promising. Although, again, the ullage was very good, there were some sticky traces of leakage. I gingerly removed the cork which was on the verge of disintegration.

I took a sip, then decided to come back to it later. Old wines surprisingly often need a little air to knit back to life, just the opposite of conventional wisdom that air will suddenly convert them to vinegar. When I finally got around to tasting it, the word “tired” would be the best description – a bit maderized, still some fruit, still barely drinkable, but mainly the savory flavors of dried spices that had spent too many seasons in a McCormick’s shaker.

Evidently, even well-made aged Chambourcins have their limits.

68