Limestone soils get a great deal of adulation from wine aficionados. Many of the great winegrowing areas of France are underlain by limestone terroir. Chablis, the Côte d’Or, the Mâconnais, much of St. Emilion, Champagne, the Loire Valley, and many of the Grands Crus of Alsace all have limestone as a base for their soils. Is this the pixie dust of vineyard soils? Does it yield magnificent wines wherever it is found? Let’s investigate the particulars of this nearly mythic rock type.

Limestone Cliffs in Mâcon — Roche de Solutré & Roche de Vergisson

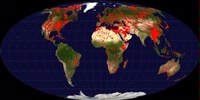

Limestone is a sedimentary rock that is widespread throughout the world.

It covers around 15% of the world’s land surface. It is classified as a carbonate rock which, in its simplest form, is a calcium ion bonded with a carbonate ion to form calcium carbonate. Ions other than calcium can combine with carbonate, so carbonate rocks encompass more that just calcium carbonate, but calcium is the most important element for our concern. Calcium carbonate is soluble in weak acids and carbonate terrains are most noted outside the wine world for their propensity to form large caves as well as house-swallowing sinkholes.

Carbonate rocks exposed around the world are in red (map by Ulrich Still)

All limestones, however, are not the same. The term limestone refers to rocks composed of 50% or more of calcium carbonate. That means 49% of the rock can be something else — clay, sand, silt, gravel or whatever. If a Pinot Noir were blended with 49% Syrah, it’s likely that the Syrah would dominate the blend. So, too, limestone can be dominated by the characteristics of its non-carbonate components. Thus, we have a complete spectrum of rocks, but a spectrum that gets split by some rather arbitrary-seeming nomenclature: A calcareous clay with 49% calcium carbonate becomes an argillaceous limestone if the percentage gets nudged up to 50%. The point is that, as scientific and precise as the geologic terminology sounds, it doesn’t quite constitute a definitive statement.

Limestone forms in warm, shallow seas. Modern limestones are being created in the Bahamas and in coral reefs dotting tropical waters around the world. Most limestones are composed of accumulated fragments of organisms that secrete calcium carbonate in their shells. Seawater has high concentrations of dissolved calcium and bicarbonate ions, so corals, clams, oysters and other sea creatures have developed the ability to synthesize these ions into hard, calcium carbonate shells. Because they contain numerous fossils, geologists study carbonate rocks closely. The fossil evidence enables a reconstruction of the depositional environment and an ability to correlate with geologic formations in other parts of the world.

The ancient sea dwellers that form limestone can be large and visible as fossil shells a meter long or tiny, with their calcareous shells visible only under the microscope. The famous chalk of Champagne is composed of the skeletal remains of billions of tiny algal organisms called coccoliths.

Coccolith magnified 15,000 times

Rock deposition is hardly a sanitary process, so sands, gravels and clays from other sources can be mixed in with the shell fragments resulting in sandy limestones, limy clays, and sandy-gravelly-limestones in all permutations. Other minerals like hematite or glauconite can get into the mix as well, resulting in red or green tints, respectively, to the rocks.

What is special about limestone then, that makes it such a mythical vineyard soil? Clearly, there are vines that benefit from limestone soils. One needs only to point to Chablis for a stellar example of “limestone minerality”. The best Chablis wines, however, are grown on Kimmeridgian sediments, which are as much clay as they are limestone. Which is the key component? Perhaps both are needed to accomplish the delicious miracle of Chablis. The great Grands Crus of the Côte de Nuits are grown on marl — a mixture of soft limestone and clay. It’s likely that the combination makes the soil especially beneficial to Pinot Noir vines.

Limestone normally evolves into a higher pH soil. Research suggests that nutrient uptake at the rootlet is greater when the pH is moderate (a 6-7 level). Calcium ions, along with magnesium, potassium and sodium ions (all cations in the chemical parlance) can be transmitted across the rootlet cell walls when the pH and water presence are ideal. The enhanced cation exchange capacity or CEC is one of several measurements that help define optimal soils for viticulture. Higher acid (lower pH) soils provide a less favorable transfer of ions. Adding powdered limestone to these low pH soils has proven beneficial for plant growth — a testament to the power of the rock.

Too much limestone, however, can be detrimental to vines. The vine malady chlorosis is often related to excessive lime and too high a pH in the soil. Chlorosis is a yellowing of plant leaves due to an iron deficiency. The lack of green matter results in weak photosynthesis and thus weak plant vigor. High lime soils cause iron to react and be bound up in insoluble forms and thus unavailable to the plant. This became particularly evident in post-phylloxera times, since North American rootstocks did not take well to the high lime content of many French soils. Obviously, too much limestone is a hindrance to great wines and, once more, we must seek balance among components to achieve greatness.

Vine leaf affected by chlorosis (right)

As we have noted, limestone is exalted as a soil in many parts of France. Much is made of the few areas of limestone soils in California — Chalone, Mt. Harlan and a few others — as superior sites for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Limestone provides a good habitat for many other grape varieties around the world. The higher elevations of Tuscany are noted for limestone soils and Sangiovese wines. South Australia’s Coonawarra owes its famous ‘terra rossa’ soil to limestone and is famed for Cabernet Sauvignon. The Right Bank of Bordeaux has abundant limestone in the soil and grows primarily Cabernet Franc and Merlot. Limestone underlies vineyards of Negroamaro grapes in Apulia, Verdicchio grapes in Marche, Agioritiko grapes in Greece’s Nemea region and much, much more.

Coonawarra Terra Rossa Soil (Wynns Coonawarra Estate)

It is clearly evident that all of the grape varieties grown successfully in highly calcareous soils can also produce fine wines in areas bereft of limestone. Is there a common thread of greater finesse and complexity among limestone-based wines? That’s an argument that will fill pages of discourse and will likely never be solved. To sum up, limestone isn’t everything, but it is a piece of the puzzle in the grand complex of factors that make wines distinctive and appealing.