The impressive force exerted by flowing water sculpts many of the landforms we see throughout the world. To a geologist, these are fluvial forces and the various gravels, sands and clays they deposit are known as alluvial sediments or alluvium. While rivers and streams arguably influence all landscapes in some respect, their power and the sediments they leave behind have a dramatic influence on many of the worlds most famous vineyard regions.

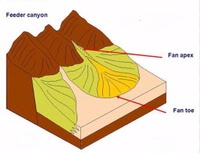

Block Diagram of an Alluvial Fan

For the moment, we will focus on a subset of alluvial sediments known as alluvial fans. Alluvial fans are named for their often fan-like appearance. They are formed when a stream emerges from an upland area into an adjoining valley. As streams descend from high elevation at a steep gradient, they naturally flow rapidly. The strong current carves the surrounding landscape, eroding its banks and pulling the surrounding material down with it. These montane watercourses can have considerable capacity to carry cobbles, gravel, silt, sand and clay, especially in times of flood and high flow.

As our stream or river emerges into a valley, the gradient diminishes markedly, the flow rate decreases and the carrying capacity drops substantially as well. Thus, the water loses much of its energy and can no longer carry the coarse-grained alluvium along. Alluvial fans almost always consist of coarse-grained, poorly sorted deposits since the energy loss of its transporting medium is profound and leads to rather random deposition patterns.

Over time, more and more sediments are deposited and the accumulated mass becomes big enough to block the flow of water, causing the original channel of flow to split as water flows around the obstruction. The process continues until many distributed channels of water create a shape that resembles a segment of a cone, radiating downslope from the point where the channel emerged into the valley. The narrow portion of the fan is known as its apex, and its widely-spread conical region is known as the fan’s toe or apron. Alluvial fans vary in size from tiny to enormous, ranging from a few square centimeters to fans in the Himalayas that cover thousands of square miles

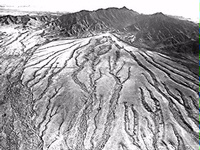

Alluvial Fan Near Tucson AZ

Sediments high on alluvial fans tend to be rich in gravel with cobble- and boulder-sized rock fragments while the toe of an alluvial fan typically consists of sand-, silt, and mud-sized fractions. The most definitive studies of alluvial fans have been in arid environments, where the geometry is vividly displayed without a cloak of vegetation. Many factors control the shape and composition of alluvial fans, including the character of the eroding bedrock in the source area, the frequency of floods, vegetation cover, and the geometry of the valley into which the sediments are being deposited. Alluvial fans can merge with other fans to form apron like structures along mountain fronts (called a bajada).

Alluvial fans have many of the same geometric characteristics as deltas, but there are key differences. Alluvial fans have a steep slope and an abundance of coarse-grained sediments, which may include boulders. They are usually caused by large flash floods or debris flows. River deltas, while they have a similar fan shape, have a shallow slope, are comprised of fine-grained sediments dominated by sand and mud, and are usually formed by the spreading of a river where it enters a body of water, such as lakes, oceans, etc.

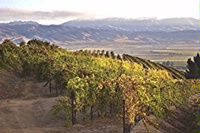

Napa Valley Vineyard on an Alluvial Fan

Where in the wine world are alluvial fans important for vineyard locations? We find fans throughout the world in areas where there is a significant change in slope between a viticultural valley and its surrounding highland areas. These tend to be in geologically active areas, where mountain building and associated faulting has influenced the topography.

California offers fine examples of vineyards on alluvial fans. Vines in Rutherford and Oakville in Napa Valley are frequently on alluvial fans brought down from the Mayacamas Mountains. On the east side of the Napa Valley there are alluvial fan influences as well. The famed Three Palms Vineyard is located on an alluvial fan created by the outwash of Selby Creek where it spills out of Dutch Henry Canyon. The site is covered with volcanic stones washed down from the canyon resulting in the spare, rocky and well-drained soils that yield legendary Merlots from this site.

Alluvial Fan Vineyard in the Santa Lucia Highlands

In Sonoma County, the Alexander Valley is noted for its well-drained vineyards on alluvial fan deposits. The Russian River Valley has many Pinot Noir sites that rest on the gravelly sediments of alluvial fans. Further south in Monterey County, the Santa Lucia Highlands Pinot Noir and Chardonnay vineyards are often located on alluvial fans that spread out from streams in the Santa Lucia Mountains.

In France, alluvial fans provide a well-drained base for vineyards in Alsace. As streams like the Fecht, Lauch and Strengbach tumble out of the Vosges Mountains, they have formed alluvial fans when they empty into the Rhine Valley. Zind-Humbrecht’s fine Herrenweg vineyard lies on the alluvial fan of the Fecht. The pattern repeats as we move northward through Alsace and into the Pfalz of Germany.

Italy has notable vineyard sites resting on alluvial fans as well. In the Alto Adige, many fans have formed as rivers and streams drain the uplands of the Alps and empty into the broad Campo Rotaliano. The vineyards here support red grapes like Teroldego and Lagrein as well as whites like Pinot Bianco, Pinot Grigio and Traminer.

Alluvial Fans Adjoin the Mountains of Stellenbosch

In the southern hemisphere, there are alluvial fans in many growing regions. The steep slopes of mountains in Stellenbosch have invited the formation of alluvial fans based on the weathered granites and sandstones of the mountains. In Chile and Argentina, alluvial fans on both sides of the Andes offer well-drained soils for the Bordeaux varieties that are planted here.

There are many areas of the world where alluvial fans are essential elements of the landscape. Wherever mountains meet plains, alluvial fans are a natural consequence of the juxtaposition of gradients. Look for the distinctive conical shapes the next time you visit a valley of vineyards.