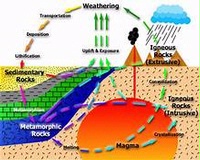

We have discussed the rock cycle in past columns. There are three basic categories of rocks, igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic. They are all connected in the endless rock cycle. Sedimentary rocks form as deposits accumulate in the seas (most often) and are compressed and lithified. Metamorphic rocks begin as sedimentary rocks and then undergo sufficient heat and pressure to change the character of the rock. Sometimes the heat and pressure increase to a point when the rock melts — this is the process that ultimately forms igneous rocks. Once igneous, or any type of rock is uplifted to the Earth’s surface, it is subject to weathering, erosion and deposition as the start of new sedimentary rock, and the cycle is complete.

The Rock Cycle

The term “igneous” has its etymoIogical roots in “ignis,” the Latin word for fire. A characteristic shared by all igneous rocks is that they are formed in a molten state. They can vary significantly in chemical composition and in crystalline structure. The character of the igneous rocks we observe is dramatically affected by the manner in which they reach the Earth’s surface. Molten rock (magma) that cools slowly, sometimes thousands of feet below the surface, and develops large crystals of its component minerals — a phaneritic texture in the geologic parlance. If magma reaches the surface in a molten state, it is known as lava. Igneous rocks formed from lava cool quickly. The mineral components do not have time to form visible crystals and the rocks have what is called an aphanatic texture. Thus, rocks of the same basic chemical composition can have different names due to the dynamics of their formation. Rock formed from lava is called extrusive. Rock from relatively shallow magma is called intrusive. The very deep-buried magmas, which cool the slowest and form the largest mineral crystals, are called plutonic rocks.

Granite, an Intrusive, Felsic Igneous Rock

Igneous rocks can also be classified by their mineral content. The main minerals in igneous rocks are feldspar, quartz, amphiboles, pyroxenes, olivine and permutations of the softer mineral mica. The two best-known igneous rock types are granite and basalt. These rocks have distinctly different chemical compositions and textures. Granite is generally a light colored, coarse-grained rock formed at depth — therefore intrusive or plutonic in origin. It is rich in the minerals feldspar and quartz (silica) and, in the geologic parlance, is called a "felsic" rock.

Basalt is the dark in color and fine-grained and its lavas can flow easily and extend over great distances. Its component dark minerals are rich in magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe) and basalt is thus called a "mafic" rock. In the case of basalt flows like those that created the Columbia Plateau of eastern Washington, it is an extrusive igneous rock.

In the wine world, we are very cognizant of granite-based soils. Gamay vineyards in Beaujolais are famous for granitic soils. So too, Syrahs from Hermitage, Muscadets from the Pays Nantais village of Clisson, Rieslings from some Alsace Grands Crus, and Viogniers from Condrieu are all French examples of wines from granitic soils. Wines from Paarl and Stellenbosch in South Africa, Dão in Portugal, Rías Baixas in Spain and the Sierra Foothills of California share granitic underpinnings as well.

Rhyolite, an Aphanatic, Felsic Igneous Rock

Granite is categorized as a phaneritic igneous rock that contains 68-75% silicon dioxide by weight. The fine-grained, or aphanitic igneous rock with the same chemical composition is rhyolite. Its high silica content affects the physical properties and fluid dynamics of rhyolitic lavas. They are very viscous and for that reason tend to be associated with violent volcanic eruptions. In the wine world, we find the vineyards of the Greek island of Santorini, among others, on rhyolite lavas that were deposited during explosive eruptions. The ancient volcanic deposits of Tokaj in Hungary are rhyolitic and underlie many of the top Tokaji vineyards.

Vineyard on Rhyolitic Soil in Tokaj

In the new world, we find rhyolite as a common soil base in the Napa and Sonoma appellations in California. Volcanic activity associated with the eruptions of Mount St. Helena is likely the source of these rocks. Some very famous vineyards on the eastern benchlands of the Rutherford AVA as well as the Howell Mountain and Stags’ Leap AVAs and throughout the Knight’s Valley AVA are planted on rhyolite-based soils. Cabernet Sauvignon, Zinfandel, Chardonnay and more are all planted with great success on the rhyolitic terrain.

Let’s consider the mafic (magnesium + iron) igneous rocks. Basalt is the famous one. In most cases it is an extrusive igneous rock with a fine-grained, or aphanatic texture. Basaltic lavas are noted for their fluid nature, often flowing for miles from their source before they cool to a stop.

In the USA, the best-known basalt-based area is the Columbia Plateau of eastern Washington State. Basaltic soils are common in the Willamette Valley of Oregon as well. Other basaltic terroirs of note in the wine world are the island of Madeira, vineyards near Hungary’s Lake Balaton plus vineyard sites in the Pfalz and Ahr of Germany.

If basalt is the extrusive, aphanatic form of mafic igneous rock, what is the coarse-grained phaneritic equivalent? The rock in this case is called gabbro. It is less commonly exposed throughout the world. The most noted spot in the wine world for gabbro-derived soils is in the Pays Nantais of France. In the Muscadet de Sèvre et Maine appellation, the village of Gorges is noted for its gabbro-based soils as well as its characterful, ageable wines.

Muscadet Vines Planted in Gabbro-Based soil of Gorges

That’s a brief glimpse at some of the igneous petrology factors that influence the wines we enjoy. With so many grape varieties planted in the various sites, it’s extremely difficult to find a common thread that will tie together wines from soils that share the same geochemistry but differ in texture. The next time you visit a vineyard, look around and get your hands a little dirty. Feel the grain of the rocks and the texture of the soils. Whether geology is a critical factor or not, the combination of earthly factors that makes great vineyard sites distinctive should always be noted.