The wines of Madeira are among the most historic and unusual in the world. With a mythic history of discovery and plantation, Madeira wines have been alternately exalted and ignored by the world’s wine consumers for over four centuries. A favorite in colonial America, Madeira was the wine of choice for many a gathering during the struggle for independence.

The Rocky Cliffs of Madeira

A visit to Madeira reveals a very unusual wine growing area. The six thousand foot high island is rugged, with steep slopes and cliffs dropping down to the ocean. If you want a flat place on Madeira, you probably need to make it yourself. Because the basaltic rocks are hard and difficult to work, many vineyards on the island are terraced — making a flat place to tend the vines. A related factor is a profusion of small growers on Madeira, some with just a backyard plot of vines. Madeira negociants branch out and often need to coordinate with hundreds of growers to bring in the harvest.

Small Vineyard Plots on Madeira

Madeira wines are also distinctive for their vinification process. The winemaking history was developed when sailing ships from the European mainland would stop at the island for provisions. They would put barrels of the tart and acidic wines of the island into the ship’s hold as ballast, and also to allay the effects of scurvy on the crew. Shippers found that after an equatorial crossing or two, the wines came back better for their journey. Today, the heating is done in the winery, either in a heated tank called an estufa or set to age in barrel in the subtropical heat of the island.

The geologic origin of the island frames the landscape of Madeira’s vineyards. The island lies in the Atlantic Ocean, about 600 miles southwest of Lisbon. It is actually closer to Morocco than to Portugal. The island of Madeira is part of a small volcanic archipelago of the same name in the Atlantic Ocean, first known to the Romans and then rediscovered by Portuguese sailors around 1419. Of the island chain, Madeira is the largest and most populated island.

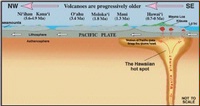

It is thought that volcanic eruptions formed the islands when the Eurasian Plate moved over a hotspot in the same way the islands of Hawaii formed. The lava that formed Madeira reached above the ocean’s surface about five million years ago.

A Representation of the Hawaiian Hotspot as the Pacific Plate Moves Over It

Unlike volcanoes that form when tectonic plates collide on the leading edges of continents — the Cascades and Andes for examples — a hotspot is theorized to form as one of Earth’s outer tectonic plates moves over an unusually hot part of the Earth’s mantle. Large amounts of magma rise up, piercing through the plates and producing large volcanic eruptions at the Earth’s surface.

The mantle plumes that form hotspots are thought to be relatively stationary, while tectonic plates are not. As the plates continue to move away from the hotspot, the volcanoes cool and subside. Erosion takes over, especially in a tropical climate, and the formerly erupting volcanoes are worn away, producing older islands, atolls, and seamounts.

A volcano might stay active for two or three million years while it is directly above the hotspot, building in elevation with successive lava flows. As the tectonic plate moves away, however, its volcanic activity begins to fade. Eventually it lapses into quietude, only to be replaced by a new volcano being born on the ocean floor that has moved on top of the hotspot.

This is occurring today in Hawaii, perhaps the most well-known example of a hotspot track. In the Hawaiian Islands, there is a clear age progression, getting progressively younger in their radiometric dates as you move east. Kauai rocks are 3-5 million years old. Oahu rocks are dated at 2-3 million years of age, Maui’s at one million years, and Hawaii’s volcanoes are still erupting. A new volcano called Loihi is seamount erupting east of Hawaii and, in the next million years or so, will become the next island in the chain. The Hawaiian hotspot is believed to have been active for at least 70 million years, producing a volcanic chain that extends 3,750 miles across the northwest Pacific Ocean.

A Diagram of the Madeira Hotspot Island Chain

Madeira Island is a shield volcano, an island formed by repeated eruptions of large amounts of lava. The rocks that form Madeira are basalts, similar to those found in Hawaii. There is a similar age track as well, with Madeira Island some 5 million years old, Porto Santo to the north is 14 million years old, and significant submerged volcanoes (aka seamounts) successively older to the north of Porto Santo. There is some disagreement among geologists about the whether the hotspot theory fully applies here, but that is a topic for another day.

The delight of Madeira wine is its longevity. By most standards, the wine has been completely abused in the vinification process. It has been heated for months at a temperature well beyond what a winemaker on any continent would permit. It is stored in large casks that are not kept full for many years in the cellars. Such treatment would destroy most wines, but Madeira endures. The rules for Vintage Madeira require twenty years of cask aging — a process few other wines could endure. Even after a century or more, fine Vintage Madeira continues to improve. It is durable once opened as well. If you have not yet sampled the glories of a century-old Madeira, they can still be found on wine lists of fine restaurants and shops. It is worth the effort and expense for wine lovers to seek them out and enjoy the best that this volcanic mountain in the Atlantic can provide.