Recently, I attended a phenomenal tasting of Blandy’s Vintage Madeiras, dating back to the early 19th century. The setting was the roof of a spectacular new hotel in Cooper Square, in lower Manhattan. The hotel was too hip to be real, marking a dramatic comparison with these very traditional old wines. But the tasting did remind me how much I love old vintage Madeiras.

Madeira, a fortified wine, at its best is one of the world’s great wines, an original. It is produced only on the sub-tropical island of Madeira, in the Atlantic Ocean, nearer to Africa than Europe. Madeira is a volcanic island, with steep hillside vineyards rising practically straight up from the ocean. It is a province of Portugal, although the British have always run its wine trade.

I discovered vintage Madeira quite by accident. Back in the mid or late 1970s, Sherry-Lehmann, the New York wine shop that has become an institution, mentioned in one of its newspaper ads that it had vintages of Madeira for sale, with many of the bottles dating back to the 19th century. The prices for these wines ran from about $75 to less than $200 a bottle—really low considering their age and scarcity.

I discovered vintage Madeira quite by accident. Back in the mid or late 1970s, Sherry-Lehmann, the New York wine shop that has become an institution, mentioned in one of its newspaper ads that it had vintages of Madeira for sale, with many of the bottles dating back to the 19th century. The prices for these wines ran from about $75 to less than $200 a bottle—really low considering their age and scarcity.

I read up on Madeira, realized what a bargain the advertised wines were, and bought about 37 or 38 bottles over the next few months. I supplemented the supply slowly over the next few years. Today, I still have about 20 bottles left from those purchases, with vintages ranging in age from 1827 to 1910. I drink about one bottle a year. Vintage Madeiras from that time period are in the $500 to $1,000 price range today, and difficult to find. Even at these prices, they are a great value, when you compare their prices to old Bordeaux or Burgundy, or even old Sauternes and Vintage Port.

Madeira was an “in” wine 200 to 250 years ago. It was the main wine that American colonists drank; the Brits managed to blockade French wines from our shores during the Revolutionary War, but the colonists were able to obtain Madeira.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Madeira’s vineyards were devastated—first by mildew and then by the phylloxera louse (just as in Europe’s vineyards). Unlike Europe, tiny Madeira took a very long time to recover, until well after World War II, and many observers believe that the Madeira wine trade has never fully recovered.

Most vineyards were re-planted with easier-to-grow, lesser grape varieties. The original five varieties—Sercial, Verdelho, Terrantez, Bual, and Malmsey—always presented a challenge to grow, like so many other noble grape varieties. A little bit of wine is still made from four of these varieties—Terrantez has practically disappeared—but the best Madeiras are definitely the old vintage Madeiras, from 1920 back to 1795.

Most vineyards were re-planted with easier-to-grow, lesser grape varieties. The original five varieties—Sercial, Verdelho, Terrantez, Bual, and Malmsey—always presented a challenge to grow, like so many other noble grape varieties. A little bit of wine is still made from four of these varieties—Terrantez has practically disappeared—but the best Madeiras are definitely the old vintage Madeiras, from 1920 back to 1795.

Many consumers probably only know about Madeira as an inexpensive cooking wine, but I’m not talking about that here, nor am I referring to any Madeira wines labeled dry, medium-dry, medium-sweet, or sweet. These wines definitely are not made from the five noble varieties I mentioned above. Madeira wines labeled 15 years old, 10 years old, or even five years old, are a considerable step up, but are still not of the quality of vintage Madeiras made from the five noble varieties.

The dominant grape variety in most of today’s Madeira production is Tinta Negra Mole, a less noble red variety that grows prolifically on the island, and is not prone to the diseases of the noble varieties. The noble varieties thrive only in vineyards close to the ocean, but the urban sprawl of Funchal, Madeira’s capital, is impinging on them.

Sercial and Verdelho, the two dryer varietals, have alcohol added after fermentation. Terrantez, Bual, and Malmsey (aka Malvasia), the sweeter varietals, have their fermentation stopped earlier by the addition of alcohol. Almost all of these wines have 20 percent alcohol in the finished wine.

Sercial and Verdelho, the two dryer varietals, have alcohol added after fermentation. Terrantez, Bual, and Malmsey (aka Malvasia), the sweeter varietals, have their fermentation stopped earlier by the addition of alcohol. Almost all of these wines have 20 percent alcohol in the finished wine.

Nowadays most Madeira is made with a unique baking process called estufagem, following fermentation. The fact that Madeira improves by heating was discovered accidentally back in the 17th century. Trading ships back then used to cross the equator with casks of Madeira in their holds, to act as ballast. When people tried these heated Madeiras, they found that the wine had actually improved! But the modern method, estufagem, is a bit more practical than sending Madeira around the world in a slow boat.

After a three-month heating process, either in estufas (heating rooms) or exposed to the year-round sun on the island, the natural grape sugars in the wines become caramelized, and the wine becomes thoroughly maderized without developing any unpleasant aroma or taste.

The canteiro method of aging (the wine is left in warm lofts or exposed to the sun for up to three years) is more expensive, but is the best method, because the wines retain their high acidity, color, and extract much better in the slow-aging process. Only the finer Madeiras use this method of aging.

The canteiro method of aging (the wine is left in warm lofts or exposed to the sun for up to three years) is more expensive, but is the best method, because the wines retain their high acidity, color, and extract much better in the slow-aging process. Only the finer Madeiras use this method of aging.

Madeira starts as a white wine, but the heating process and years of maturation (20 years minimum in cask for Vintage Madeira) gives it an amber color with pale green reflections. It has a tangy aroma and flavor that is uniquely its own, and has the longest finish on the palate of any wine in the world. The natural acidity in the wine prevents it from ever tasting cloying.

You never have to worry about Madeira getting too old; it’s indestructible. The enemies of wine—heat and oxygen—have already had their way with Madeira during the winemaking and maturing process. Nothing you can do after you open a bottle will affect it. I usually keep my bottle of Madeira about two weeks after I open it, enjoying a sip mid-afternoon or after dinner.

By the way, store Madeira standing up. It cannot get oxidized from aeration. But the natural sugars in the wine can play havoc with the cork if you store it lying on its side.

Besides Vintage Madeira, which is the best, you can also find somewhat less expensive bottles of older Madeiras dated with the word Solera, such as “Solera 1863.” This is not Vintage Madeira but a blend of many younger vintages whose first barrel (solera) dated back to the named vintage, in this case, 1863. These Solera Madeiras, which are not made any more (too confusing for the consumer), can be quite good, but not on the same level as Vintage Madeiras.

Besides Vintage Madeira, which is the best, you can also find somewhat less expensive bottles of older Madeiras dated with the word Solera, such as “Solera 1863.” This is not Vintage Madeira but a blend of many younger vintages whose first barrel (solera) dated back to the named vintage, in this case, 1863. These Solera Madeiras, which are not made any more (too confusing for the consumer), can be quite good, but not on the same level as Vintage Madeiras.

In place of Soleras, a new style of Madeira, called Colheita Madeira, is now being produced. Like Solera and Vintage, Colheita Madeira is made from one noble grape variety, and like Vintage Madeira, from one year or vintage. The difference is that Colheita Madeira only has to be aged five years in the cask (seven years for Sercial) instead of the minimum 20 years for Vintage Madeira. As a result, Colheita Madeira is much less expensive than Vintage Madeira. Since this style was introduced about a decade ago, Madeira sales have doubled.

In the 19th century, when Madeira was at its height, more than 70 producers were shipping Madeira wine around the world. The phylloxera devastation wiped out many companies; others consolidated. Today, the Madeira Wine Company dominates the business. It is mutually owned by Blandy and the Symington Port family, although Michael Blandy and his son Chris, 6th and 7th generation Blandy, run the company. The Blandy Company was founded in 1811. Its other major brands are Cossart Gordon, Leacock’s and Miles.

The four major noble varieties still being produced in small quantities are the following:

Sercial—This variety grows at the highest altitudes, is the least ripe, and makes the driest Madeiras. An outstanding apéritif wine with almonds, olives, or light cheeses. Quite rare today; a personal favorite.

Verdelho—Medium-dry style with nutty, peachy flavors and a tang of acidity. Fine as an apéritif or with light soups, such as consommé.

Bual—Darker amber in color. Rich, medium-sweet Madeira with spicy flavors of almonds and raisins, with a long, tangy finish. Best after dinner.

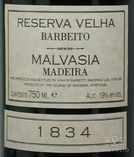

Malmsey—Made from the Malvasia grape variety. Dark amber, sweet, and intensely concentrated, with a long finish. Drink it after dinner.

Two very rare varieties, mainly available in old bottles:

Terrantez—Medium-sweet (between Verdelho and Bual in style). Powerful, fragrant, with lots of acidity. For some Madeira lovers, the greatest variety of all. Very little available today; one small producer, Henriques & Henriques, still makes it. Drink it after dinner.

Bastardo—The only red grape of the noble Madeira varieties. Old Bastardos from the 19th and early 20th centuries are mahogany-colored and rich, but not as rich as Terrantez. In style a cross between Bual and Malmsey. Very prone to disease.

Blandy’s recent tasting in March, celebrating the bicentenary of the company’s founding, included one Colheita, seven “modern” Vintage Madeiras dating back to 1948, six old Vintage Madeiras dating back to 1822, and one Solera 1811, the year of its founding. A brief description of the wines follow:

Blandy’s Malmsey Colheita 1994: Blandy’s first Colheita, introduced in 2000, was six years old. This 1994 Colheita was aged for 11 years in cask. Tastes of orange peel and sweet plums; honeyed, caramel, high acidity, fresh; silky texture. Retails in the $38 to $48 range.

Blandy’s Malmsey 1985: Already showing complex flavors; a big step up from the Colheita. Aromas of toffee, with orange peel flavors. Warm, naturally sweet, lovely, with great acidity. Aged 25 years in cask. Has reached its potential, according to the winemaker. $128-$130.

Blandy’s Terrantez 1976: Aged for 26 years in the warm lofts of Blandy’s wine lodges. The first truly great Madeira of the tasting; extraordinarily complex; very concentrated, with terrific acidity. A rare, amazing wine. In the $185 to $250 price range.

Blandy’s Sercial 1966—Oh, yes! Dry, incredible finesse; the very high acidity has a whiplash effect. Crisp, less weighty than previous wines, but lots of depth. Long, sleek finish of orange and lemon flavors. Still young and fresh, although aged for 28 years in cask. Just fantastic; this wine will live indefinitely. $187-$190.

Blandy’s Bastardo 1954—Just the second Bastardo I’ve ever tasted. The last Bastardo made by Blandy’s. Aged for 40 years in cask. As rich as Malmsey, but lower in acidity than the other noble varieties. Prized for its rarity more than anything else. Not available.

Blandy’s Malmsey 1954—Bottled in 1975. A great vintage for Malmsey. Sweet, soft, and ample, with good acidity. Very good, but not one of my favorites. Not available.

Blandy’s Sercial 1950—Aged for 31 years in cask. Incredible length; high acidity. Lemon twist flavor for me, other said tart or bitter lemon. Excellent concentration. Not quite as great as the sublime 1966 Sercial. Not available.

Blandy’s Bual 1948—Aged 56 years in cask; bottled in 2004. Outstanding wine, with a very long finish. Rich, sweet, carmelized, with lemony acidity. A fleshy wine; its concentration and bitter orange finish makes it a standout. In the $319 to $450 price range.

Blandy’s Bual 1920—An exceptional vintage for Bual; bottled in 2006. Incredible length on the palate. Rich and sweet, with tons of acidity. A perfect, sweet-tart wine, Bual at its best. Outstanding! $572 to $775.

Blandy’s Sercial 1910—An all-time great year for Sercial. Amazingly fresh and vital; length on the palate is astounding. Long, bitter-lemon and orange finish. Focused and precise. I’ve tasted this wine a few times previously. It’s why I Iove Sercial. What the 1966 Sercial will become. $615 in the UK; presently unavailable in U.S.

Blandy’s Terrantez 1899—Perhaps the greatest vintage for the rare Terrantez. Re-bottled in 1986. Rich, unctuous, with exceptional acidity; finishes bone dry. Powerful, with great concentration; coffee notes on the finish. Not available.

Blandy’s Terrantez 1870—Aged for 51 years in cask, bottled in 1921, re-bottled in 1986. The other great vintage for Terrantez. This particular bottle was fragile, with a trace of oxidation, light brown color, but lovely, and holding fine for a 141-year-old wine. I’ve had this vintage Terrantez before in better condition. The acidity is holding it together. Other tasters thought it was brilliant, better than the 1899. Not available.

Blandy’s Bual 1863—Perhaps the greatest vintage for Bual. Aged for 50 years in cask; re-bottled in 1986. Amazing length; rich, with depth of flavor; roasted coffee aromas, firm structure, with lime notes on the finish. I gave the 1920 Bual a slight edge. But an amazing 148-yeqr-old wine. $664 in the UK; presently unavailable in U.S.

Blandy’s Verdelho 1822—Matured for 78 years in cask, re-bottled in 1986. Orange peel aromas, high acidity, the first Madeira of the tasting that had flavors of fresh apple. One taster said, “Calvados.” Rich with caramel flavors as well; lots of grip on the palate. Very lovely, but not one of my favorites. Doing well for an 189-year-old wine! Very few bottles remain of this Verdelho. Not available.

Blandy’s Bual Solera 1811—Matured in cask for 89 years; bottled in 1900, re-bottled in 1986. According to Chris Blandy, this solera contains about 10 percent of the 1811 vintage. The average age of the vintages is in the 50 to 60 year-old range. A very fine Madeira, but an anti-climax to some of the sublime Vintage Madeiras that preceded it. Not available.

My favorite Madeiras of the tasting, from youngest to oldest, were the following: Terrantez 1976; Sercial 1966; Sercial 1950; Bual 1948; Bual 1920; Sercial 1910; Bual 1863. Narrowing it down to my top three: Sercial 1966, Bual 1920; Sercial 1910. I really can’t decide among those three which was my favorite. But I can tell you that I’m now going to drink at least two bottles of Madeira a year, perhaps even three!