Much has been written and spoken about the connection, or lack thereof, between great vineyard sites and their underlying geology. There are many points of discussion and certainly differences of opinion about the degree of influence. The recent dialogue in the wine press about “minerality” in wine continues a long-standing debate about the importance of terroir.

I agree that there is no science that shows a human can taste limestone, granite, or any other rock type in wine. As students of wine, we know that wines grown on different soils smell and taste differently, but we must logically conclude that it is not the taste of the rock. Soils do make a difference in wine quality, but it likely has more to do with organic  composition, pH, drainage and cation exchange capacity than rock type. New investigations of microflora and microfauna assemblages in soils of distinctive wine regions may shed some light on the reasons for their superiority, but for now we can consider it as part of the magic of terroir.

composition, pH, drainage and cation exchange capacity than rock type. New investigations of microflora and microfauna assemblages in soils of distinctive wine regions may shed some light on the reasons for their superiority, but for now we can consider it as part of the magic of terroir.

Geology, however, is not just the study of rocks and their derivative soils. The study of geology encompasses the natural upheavals that have created the wild diversity of landforms (and undersea forms) of the earth. It requires an understanding not only of the forces that create and destroy the earth’s surface, but also of geologic time. The geologist must understand that these formidable powers are active every day but are rarely fully comprehended because they happen so slowly when compared to a human’s lifespan. Like a persistent, inquisitive toddler, the geologist must always be asking “Why?” The study of geology informs not just the rocks  underlying the hillside, but why the hillside is there at all. Which of nature’s powers combined to create the topography we observe today? If the soil is heavy with clay, how did the clay get there? It’s not enough to know what is; we want to know why it is as well.

underlying the hillside, but why the hillside is there at all. Which of nature’s powers combined to create the topography we observe today? If the soil is heavy with clay, how did the clay get there? It’s not enough to know what is; we want to know why it is as well.

It is obvious to all that differences inherent in vineyards render them superior or inferior. We can be certain that landholders adjacent to famous and classic vineyard sites tried, in some cases for a thousand years, to replicate the wines of their famous neighbors and consistently failed to do so. Thus, grape growers know that specific sites consistently yield better or lesser quality fruit. The site differences may range from a few rows in a vineyard block to a sweet spot on a hillside, to a whole winegrowing region. Piecing together the complex puzzle of factors that result in superior vineyard sites enhances one’s understanding of the true meaning of terroir.

In a broad sense, geology plays a key role in determining the relative quality of a vineyard or winegrowing region. As a study of the forces that shape the earth, every specific site, vineyard or not, has a geologic story behind it.

Consider the vineyards of the Côte d’Or — a geologist’s playground among winegrowing areas. We can define a number of geologic influences that allow exemplary wines to be made here.

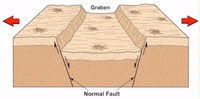

We know that the Côte d’Or vineyards are aligned in a northeast to southwest manner, giving the perfect southeastern exposure for the vines. The alignment is completely due to the geologic structure and history. As Africa collided with Eurasia some 30 million years ago the Alps were pushed up by the collision. Attendant to the uplift, the earth’s crust bordering the Alps was stretched and cracked along planes of weakness that are the fault zones we see today.

Image: NASA

The Saone Fault, which forms the face of the Côte d’Or, was part of a fault bundle that is a down-dropped block, or graben in geologic terms. This is no small movement, as there is nearly five thousand feet of displacement along the Saone fault. Fortuitously for winelovers, the rocks exposed along the fault scarp were a series of Jurassic age limestones and marls that became the advantageous slopes and soils of the Côte d’Or.

Had the axis of the fault been rotated 90 degrees, we might have the same geologic structure but with northeast facing slopes which would not have permitted full ripening of grapes at this latitude. Had the angle of the fault been less steep, we might not have adequate drainage to support great vineyards.

It is, however, the wonderful coalescence of geologic circumstance that results in arguably the world’s finest expressions of both the Pinot Noir and Chardonnay grapes grown in juxtaposition. The geologic forces exposed the perfect sequence of Jurassic limestones and marls along the perfect fault alignment with the perfect angle to the sun and drainage, at the perfect latitude to produce these great wines.

You don’t need to look far to find similar geologic influences on familiar wine regions. Within France, the Mâconnais, Beaujolais, Northern Rhône, Alsace and other areas all owe part of their distinction to the geologic faults that define them. The Rhine vineyards of Germany share a similar geologic influence. New Zealand’s Marlborough and Otago, the Santa Lucia Highlands, and many of California’s growing regions are fault-bounded — and the list goes on.

The structural geology is just one part of the geologic puzzle. Many noted winegrowing areas are directly affected by past volcanic eruptions. Glaciers have molded others. Studies of geologic history can tell us why the famous chalk of Champagne is where it is, how the dark slate of the Mosel Valley was formed, or why the Terra Rossa of Coonawarra is in that specific spot in South Australia. The more you know about the unique history of your favorite wines, the more you appreciate how special they are.