I’ve come to the little town of Céret in southwestern France, home of one of the two Diam cork factories–the second is located in Spain. As I make my way across the parking lot, an immense blue truck rolls in, with the words DIAM El corcho reinventado emblazoned on its side. Translation from the Spanish: “Cork Reinvented.” What I am about to learn during the next couple of days here in Céret, and later visiting a handful of wineries, is that…unbeknownst to many of us wine consumers…a sort of cork revolution has been going on.

next couple of days here in Céret, and later visiting a handful of wineries, is that…unbeknownst to many of us wine consumers…a sort of cork revolution has been going on.

Humans learned to put cork to good use early on. Because of its buoyancy, cork was used as early as 3000 BC to make life vests for fishermen as well as buoys for floating fishnets on the ancient Mediterranean Sea. Its low heat conduction inspired early Romans to make beehives out of cork. Thanks to its shock-absorbing qualities, cork-soled sandals were commonly worn, and its impermeability made corkwood planks good roofing material.

Because it is flexible, as well as impermeable, cork has long been used to seal vessels of wine. From the Roman poet Horace we learn that cork, sealed with pitch, sometimes served as a plug for amphorae filled with wine, but for hundreds of years stoppers made from rags, leather, clay, sealing wax, or wood were more commonly used to seal vessels of wine and olive oil until glass bottles came into widespread use by around the 18th century.

By the 1500s, glass closures were already being used on wine bottles, but glass was expensive as well as difficult to manufacture in the days when each stopper had to be made individually, and bottles were hand-blown one at a time. Extracting a glass stopper from its bottle could be a perilous undertaking as it was hard to accomplish the task without breaking either the bottle or the stopper, or both. Finally, by the late 1600s, it became possible to create glass bottles with a fairly uniform shape and design. And then, in the late 1700’s, corkscrews came along, setting the stage for cork to replace glass stoppers altogether. Once it was discovered that corks are able to effectively seal the wine in its bottle, thereby retarding the oxidation process and allowing the wine to age and evolve slowly over time, there was no turning back.

Cork is the outer bark of an evergreen oak (Quercus Suber). Cork trees are unique in a host of different ways. It was the ancient Greeks who discovered that, when cork is stripped from the tree, a new sheath of better quality quickly forms without damage to the tree. The 200 or so different species of cork trees have much in common, including longevity (Quercus suber can live an average of 250 years). Eighty-five percent of the world’s cork trees grow in Portugal and Spain, with the rest spread across various Mediterranean regions including the French regions of Roussillon, Provence and Corsica (not all cork trees are created equal: Sicily’s cork, for example, tends to be heavy and not very flexible). Once the tree reaches maturity at 25 to 30 years old, cork can be harvested once every nine years. Cork trees tend to grow where not much else can survive, especially in hot climates, and they are more fire resistant than other trees. When managed properly, cork is a 100% sustainable and renewable material.

And now for the bad news. If you are a regular wine consumer you probably knew that the dreaded words “cork taint” were going to come up at some point. If you aren’t already familiar with it, cork taint is a flaw in a bottle of wine that is characterized by an off-putting smell and/or taste caused by the presence of the chemical compounds 2,4,6-tricloroanisole, or TCA. TCA, which is generally described as smelling something like wet cardboard, can affect any bottle of wine, at any price, and although it is harmless to humans, it will reduce or negate the wine’s natural aromas and flavors. While there are several possible causes of cork taint, the primary vector introducing TCA into a bottle of wine is the cork (and by the way, TCA can be detected by sniffing the wine, not the cork–sniffing a cork doesn’t tell you much of anything about a wine).

The number of wines affected by TCA has been decreasing in recent years due largely to improvements in the way cork is processed. By some estimates, the present rate of corked wine ranges from 3-7%. Amorin, the world’s largest cork producer, claims its current TCA level is about 0.7%. That is certainly progress, but zero percent would be even better. Other problems related to natural cork closures include the reality that natural cork can break down or crumble in the bottle over time, or it may get soggy from contact with the wine, which can make extracting it from the bottle difficult.

The only company in the world to guarantee that its corks are completely free of TCA is Diam. Recent studies have also demonstrated that Diam’s  closures better preserve the SO2 (sulfur dioxide) present in the bottle than other traditional closures, meaning that vintners could use less SO2 in the first place.

closures better preserve the SO2 (sulfur dioxide) present in the bottle than other traditional closures, meaning that vintners could use less SO2 in the first place.

I came to this industrial plant to see for myself what is being done here that might be different from other cork producers. The immaculate new factory (Diam was launched fifteen years ago) is a triumph of modern architecture designed to house the tubes and tanks and mechanical gizmos that were all whirring and chuffing away when I visited. In every room valves clattered, bells whistled, pipes puffed. A tornado of granulated cork particles whirled around in a see-through container. Fully formed corks slithered along various conveyor belts as the imperfect ones were plucked off by some sort of robotic device.

So-called “natural corks” are made from a single piece of cork, whereas "agglomerated corks" consist of cork particles held together by synthetic binding agents. Natural cork is basically considered a superior product, but unavoidable flaws such as channels, and cracks in natural corks can  make them highly inconsistent, and of course TCA is always lurking as a potential liability.

make them highly inconsistent, and of course TCA is always lurking as a potential liability.

Agglomerated cork–or technological cork, as Diam prefers to call it–is produced by reshaping pulverized cork bits and holding them together with a “glue” of polyurethane. These corks are then “satinised” with silicon or paraffin or a mix of the two. Detractors of agglomerated cork speculate that the polyurethane may present a health hazard if any of it seeps into the wine, but so far there has been no evidence of this happening, and the FDA has stated that it “identified no safety issues” with the use of binders in agglomerated corks.

As a reaction to potential problems associated with both natural and agglomerated cork, metal screwcaps have been gaining popularity since the 1990s, when Australia and New Zealand definitively embraced them. Supporters of screwcaps generally voice strong feelings about their advantages, including absence of TCA and ease of opening the bottle, while skeptics cite the possibility of issues occurring with long-term aging of wines. Consumer acceptance of screwcaps also remains a problem in some markets.

Plastic closures also have advocates (no TCA) and detractors, who find the faux corks aesthetically unappealing, hard to extract from the bottle, non-biodegradable, and less effective against oxidation. Both screwcaps and plastic stoppers are less expensive to manufacture than cork. Glass stoppers are esthetically appealing, but are costly to manufacture.

Responding to requests from both consumers and winemakers for a more “natural” agglomerated cork, Diam recently unveiled a new environmentally friendly closure, which has been named Origine®. The new product is made from cork, beeswax emulsion and a polyol, a 100% organic vegetable component. (Origine® is an addition, not a replacement, to the company’s range of products.) The cork used in

Origine® goes through the same patented process as Diam’s agglomerated corks, in which finely-milled cork granules are treated with extremely hot, pressurized liquid carbon dioxide to remove as many as 150 different molecules in the material, including TCA.

DIAM produces and sells more than 1.5 billion closures annually. Perhaps the biggest boost for the company occurred when Leflaive announced they were switching from natural cork to DIAM corks in an effort to eradicate  pre-mox, or pre mature oxidation issues. Forty percent of Burgundy producers, including Louis Jadot, Bouchard Père et Fils, and Domaine de Montille, are now using Diam closures for all or some of their production.

pre-mox, or pre mature oxidation issues. Forty percent of Burgundy producers, including Louis Jadot, Bouchard Père et Fils, and Domaine de Montille, are now using Diam closures for all or some of their production.

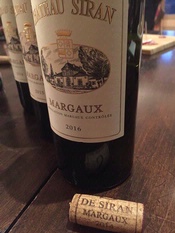

In Bordeaux, Remi Edange, the general manager at Domaine du Chevalier says he believes that Diam closures help keep white wines fresher. Eric Perrin, at Chateau Carbonnieux, told me, “We know that another advantage to Diam closures is that they help protect the wine when it is being transported.” In Margaux, Marquis de Terme Cellar Master Julien Brahmi said that Diam, “helps keep the fruit as it naturally is.” Brigitte Miailhe, who along with her husband Edouard owns Chateau Siren, said: ”We hate that thing when people open a bottle of wine and it’s corked! Since we started using Diam we haven’t had a single bottle returned. We are very happy!”

A host of other French producers have turned to Diam, including Domaines Ott, Hugel, and Trimbach. Diam claims 20% of Champagne’s  market share, including Besserat de Bellefon, Billecart Salmon, Henriot, Moët & Chandon, Mumm, Perrier-Jouët. Diam sells its corks in all 55 countries that make wine. The United States, Diam’s second biggest market after France, counts among its customers Argyle, Chandon, Constellation Brands, Domaine Drouhin, Gallo, Joseph Phelps, Shafer…and the list goes on.

market share, including Besserat de Bellefon, Billecart Salmon, Henriot, Moët & Chandon, Mumm, Perrier-Jouët. Diam sells its corks in all 55 countries that make wine. The United States, Diam’s second biggest market after France, counts among its customers Argyle, Chandon, Constellation Brands, Domaine Drouhin, Gallo, Joseph Phelps, Shafer…and the list goes on.

So, next time you pop a cork, pick it up and take a careful look. It may very well have a tiny Diam logo stamped on it next to the producer’s name. That cork will be uniformly smooth and compact.  Because it fits so snugly against the neck of the bottle there will generally be no trace of wine other than on the bottom surface of the cork.

Because it fits so snugly against the neck of the bottle there will generally be no trace of wine other than on the bottom surface of the cork.

We’ve come a long way since the days when our containers of wine were sealed with pine pitch or brittle glass stoppers.