Peter Sichel was born into the wine business that his family established in 1857. However, he didn’t get into the business himself until he was 37 years old, after an illustrious career in the OSS, then the CIA. That was after he and his family escaped Nazi Germany to New York City by way of France, Spain and Portugal with an internment camp stay along the way. He has chronicled his life and career in his memoir, The Secrets of My Life: Vintner, Prisoner, Soldier, Spy. It is a captivating story of a fascinating, and at times frightening life. He describes it as, “Really three books: growing up (Jewish) in Nazi Germany, about American intelligence and a book about the wine business, really more about the business of wine than about wine.”

books: growing up (Jewish) in Nazi Germany, about American intelligence and a book about the wine business, really more about the business of wine than about wine.”

“When you have a long life you have a lot of things happen,” he said. “Writing a memoir is like going through psychoanalysis. You suddenly look at your life from outside and you realize that a lot of things which made you are what you went through. For me it was liberating. It was good for me to write it.”

I met him when I first started judging the Los Angeles County Fair wine competition in the 1980s. I knew he was an important figure in the wine business, but like many emotionally intelligent people who have accomplished much in their lives and careers, he had no need to boast. He was then, and is still, a kind, generous, dignified, elegant and optimistic person. He is helpful with his knowledge and experience without being condescending. Even though I see him on an infrequent basis, I am always the beneficiary of his warmth and hospitality. However, he is not a pushover. He is also an astute observer and has a strong sense of what is right.

Born in Mainz, Germany on September 12, 1922, he was the first in his family to be born in a hospital. He shares memories of his parents, his sister, childhood friends in detail. He paints the picture of the life and times of a well-to-do German Jewish family: Their apartment in a building constructed by his grandfather that also housed the family wine business with the requisite barrels, hoses and pumps and packing crates. The family cook taught him to make basic French sauces. The family maids that had to be fired, on account of laws passed by the Nazis forbidding Jews to employ Gentiles under the age of 45–for purposes of ensuring “racial purity.”

He notes that his youth was marked by three periods: “…[P]eaceful and economic well-being prior to 1929, economic hard times from 1929 to 1932, and finally, the imposition of the Nazi dictatorship.” His mother predicted that the Nazis would bring about the return of the Middle Ages, but the men of the family did not become believers until the Nazis assassinated several of Hitler’s rivals within the organization in 1934, assuring his rise to power. And so began the family’s journey toward freedom.

In 1935 he and his sister were sent to separate boarding schools in England, and his parents applied for exit visas for the entire family. All  family members, except for Peter’s parents, managed to get exit visas based upon issues with the family business. A ruse involving his sister Ruth’s “near death illness” (orchestrated by the staff of her boarding school) eventually got his parents out of Germany. While the entire family had escaped from Germany, the men were charged with illegal transfer of funds, fined millions of marks, and the government seized all the family business property.

family members, except for Peter’s parents, managed to get exit visas based upon issues with the family business. A ruse involving his sister Ruth’s “near death illness” (orchestrated by the staff of her boarding school) eventually got his parents out of Germany. While the entire family had escaped from Germany, the men were charged with illegal transfer of funds, fined millions of marks, and the government seized all the family business property.

Peter’s parents settled in Bordeaux, where his father took over the family business. Peter and his sister spent their school holidays there until 1929, when France and England declared war against Germany. As German citizens, they had to report to the police as enemy aliens, and they could not get exit visas, so they had to remain in France. It was during this time that Peter began learning the family wine business.

In May of 1940, Peter, his parents and sister were ordered as German citizens to report to designated points for interment. Peter and his father were sent to one camp, his mother and sister to another. Paris fell in June of that year, and the Nazis set up their headquarters in Bordeaux. Peter and his father talked their way out of their internment camp, heading toward Spain, where they reunited unexpectedly with his mother and sister. Their plan was to go to Portugal through Spain, then to the U.S. That plan was eventually successful, but it included an unexpected and alarming event at the Spanish border. Peter was detained because of an agreement with the Spanish government to prevent entrance by any German of military age into a neutral country. He convinced the family to go on without him–but finally rejoined his family in Lisbon.

Peter explained to me the reason he believes he was able to send his family on while he stayed behind. “I had the security of my parent’s love, and I had the inner security to be able to live through it. It’s really who you are and what you are that makes a difference. It also makes you smart enough to say, and capable of saying to your family, ‘Go ahead, I will manage to join you.’ I was convinced I would, and I did. It gives you a certain amount of courage and initiative. You have trust in yourself and your fate. Sometimes it doesn’t work out, but you hope it does,” he said with a chuckle.

Peter joined the U.S. Army the week after Pearl Harbor. His fluency in French and German was soon noted, and the trajectory of his life took another turn.

Since this part of the book was about his work with the OSS and CIA, he was told by a potential publisher that he would have to get clearance from that agency before any consideration about taking on the book. “It took me three years to get the CIA to clear it,” said Sichel. “And I claim that it took them so long to clear it because they hoped I would die so they wouldn’t have to go through clearing it, but I beat them at the game.”

Peter was an early recruit in the Office of Strategic Services, OSS. His first assignment outside the U.S. was as a confidential funds clerk in Algiers, Algeria. These funds were used to support agents and underground troops in occupied Europe and, so the funds needed to be the currency of those different countries. The ingenuity sometimes required to accomplish their mission was related in an amusing story of the scheme to find French Francs in Algiers. The rumor was that the retreating Germans gave cartons of Francs to unknown citizens. Since possession of Francs was illegal for them, they weren’t anxious to admit ownership. The challenge was to find the currency and buy it in gold coins at a better exchange rate than that offered by the French. With the help of a local bar owner, whose involvement gave credibility to Peter in the eyes locals in nearby villages, Peter was able to acquire 50,000,000 francs…as well as a cellar of cognac and scotch.

Peter recounts missions on the way from Algiers to Berlin along with names of important players. He arrived in Berlin in October of 1945, finding the city in a ghastly state of destruction. It was divided into four sectors occupied by Allied forces, with free movement between them. Peter describes the lifestyle of the occupiers and the reawakening of the city’s culture despite the shortages food, shelter and fuel. He found relatives and other survivors who knew his family. He expresses wonder and bemusement at the hard-charging energy that he and his colleagues displayed at work and play, while “defending the Western world.”

The end of World War II also marked the end of the OSS. Some of the functions of its divisions were moved to other governmental agencies, such as collecting intelligence to the U.S. Army, and research and analysis to the State Department. After President Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, the CIA was born.

Peter accepted a position with the CIA after his return to the U.S., one which led him back to Berlin, where he served until 1952. He tells of the impact on the Berlin Blockade and the Korean War. But more important, Peter fell in love with Cuy Höttler, a German woman who had grown up in China. They married in 1952. Because she was German, the union required the permission of the agency, and Peter was required to transfer from Germany. The newlyweds moved to Washington, D.C., where they lived until moving to Hong Kong in 1956.

After three years in Hong Kong, Peter’s marriage was over. He decided his time with the CIA was also over, and that it was time to join the family business. He returned to New York in 1959, and began the third major phase of his life–as president of H. Sichel Sonne, a small import company.

He admits he knew very little about the wine business and had to immerse himself in learning the convoluted structure of the three-tier system, whereby producers (first tier), wholesalers or distributors (second tier) and retailers (third tier) of alcoholic beverages operate separately, ostensibly at arms-length within a complicate web of federal and state rules and regulations. He was also horrified to see that much of the business involved payoffs and bribes in money and goods. To distance himself and his company from such activity, he sold their import and distribution business to Scheifflelin & Company.

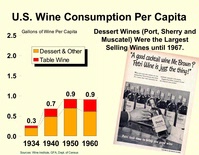

He then began to think about what products his company should make for the U.S. wine market in the early 1960s. He told me that his experience in intelligence taught him “a great deal about people’s reactions to things. What other people think and what other cultures do.” He admits that if he had been more ensconced in the wine trade, he would not have made the same decisions. What he saw was a market where table wines  were a small portion of the wine consumed by the public. A presentation created for The Wine Institute by John Fredrickson titled, Milestones in California Wine 1934-2009, showed that per capita wine consumption was nine-tenths of a gallon in 1960, three-quarters of which was fortified wine.

were a small portion of the wine consumed by the public. A presentation created for The Wine Institute by John Fredrickson titled, Milestones in California Wine 1934-2009, showed that per capita wine consumption was nine-tenths of a gallon in 1960, three-quarters of which was fortified wine.

His idea in response to this reality was…to make wine easy. At the time, they were producing many wines under the Blue Nun label. They simplified the line to one product with a specific flavor profile and supported it with a national advertising campaign that included radio spots by the comedy team of Stiller and Meara, and a national wine-by-the-glass program, which Peter states was the first in the country. Effective Radio Advertising by Marc G. Weinberger, Leland Campbell, Beth Brody (published 1994) examines the Blue Nun campaign at length because, …[It] is a classic case history of how a comprehensive, effective media plan, and its accompanying research on the competition and current playing field, will work hard to increase sales for an advertiser” (p. 43). After a long and very successful run, Blue Nun and other brands produced by the Sichels began to drop in sales in the late 1980s, so they sold the company to Langguth Erben in the 1990s.

Along the way, he met and married his wife, Stella to whom he has been married for over 50 years, and with whom he had three daughters and several grandchildren. He has published Which Wine and The Wines of Germany: Completely Revised Edition of Frank Schoonmaker’s Classic, recorded a record album, and served on the boards of countless wine education organizations. He also owned–along with some partners–Château Forcas Hosten in Bordeau’s Listrac district, which he later sold. Today, at 94, he says he’s “largely involved with family, and trying to tie up my estate before I leave. I have a very lively cultural life, with theater and music and time with friends, and a lot of reading.”

I enjoyed reading Peter’s book and highly recommend it to anyone interested in descriptions of life in Germany as the Nazis gained power, the first-hand accounts of U.S. intelligence gathering activities from the early 1940s to 1960, or how the wine business works in the U.S., Germany and Bordeaux. It is chock-full of interesting stories in the three phases of his life. The chapter, “An Informed Critique,” provides his observations and opinions on the strengths and weaknesses of our country’s intelligence gathering efforts during his years of service.

Oh, I forgot to mention the Beastie Boy thing. In their third album, Check Your Head, there’s a track called, “The Blue Nun.” It is a sheer delight to hear Peter say the group’s name in this video while explaining how the track came about: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_NAHTLDpcM

Maybe the sub-title of, Vintner, Prisoner, Soldier, Spy should have included “Rock Icon” as well.