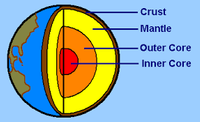

While we think of the earth as “rock solid,” the reality is not so absolute. The earth we experience is the crust, a relatively thin outer layer of our home sphere. Like an object that floats on water, the Earth’s crust “floats” on the viscous plastic rocks of the underlying mantle.

Structure of the Earth

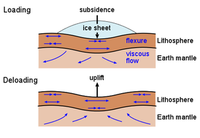

An increase in the weight of the crust, caused by ice accumulation in the case of glaciers, makes the crust sink even deeper into the plastic mantle. That is the essence of a process called isostasy. The Laurentide ice sheets that covered most of Canada and the northern United States twenty thousand years ago were thousands of feet thick. An ice mass of this dimension can weigh up to 500,000 pounds per square foot — billions of tons in aggregate. Today, ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica push the crust down two to three thousand feet. Remote sensing surveys of Greenland show that one third of its rock base is below sea level.

Isostatic Subsidence and Uplift

As the large ice-sheets retreated after the last glaciation, the land surface that is freed of its icy overburden is slowly rebounding. The viscous nature of the earth’s mantle prevents an instant recovery. The region around the Hudson Bay has risen over a thousand feet in a little over 10,000 years after the ice-sheet retreat — and the rebound is not over as the territory still has not reached its height before the last glaciation.

As the ice sheets grew and moved southward, they carved deeply into the existing river valleys, broadening and deepening as they went. The ice sheets began to retreat a few thousand years ago — a blink of the eye in geologic time. As they melted, they left five freshwater seas collectively known today as the Great Lakes — Lakes Superior, Huron, Michigan, Erie and Ontario.

Chronology of Laurentide Glacial Retreat

The U.S. Great Lakes shoreline alone totals more than 4,500 miles — longer than the U.S. East and Gulf coasts combined. The North American Great Lakes are unique among the world’s large lakes in that their basins are linked together and form one continuous drainage basin that connects Minnesota to the Atlantic Ocean. Together, they constitute the greatest freshwater system on Earth. Starting in Lake Superior, the water flows into Lakes Michigan and Huron. From there, the water flows down the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers to Lake Erie. Leaving Lake Erie, it flows into Lake Ontario via the Niagara River, over Niagara Falls and thence to the St. Lawrence River and the Atlantic. Like the oceans, the lakes moderate the temperature of the air and increase the amount of rain or snow that falls on the lands surrounding them.

During the retreat of the ice sheets, the drainage patterns of the lake states changed constantly. The complex patterns and changes are still being studied. Meltwaters initially flowed south to the Gulf of Mexico, but shifted repeatedly as the ice continued to retreat and expose new drainage outlets. Many large lakes formed along retreating the ice margins, leaving remnant shoreline sand and gravel deposits perched on hillsides today. Too, the ice sheets dropped tons of rocks, gravel and sand that now form the land surface where the glaciers melted. The current stair-step arrangement of the lake basins has only been in place for the last 3,000 years.

If you travel throughout the north-central United States, you know you are in Great Lakes country. Agriculture in many forms thrives on the lakeshores. The large lakes have a profound influence on all agricultural endeavors, but particularly for grape growing. Wine grapes, more than fruits destined for the table or processing plant, are scrutinized to determine the perfect time to pick. Many microclimates around the Great Lakes owe their viticultural prowess to the presence of these massive bodies of water.

The Lake Erie AVA stretches across New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio on the southern shores of Lake Erie. Nearly 70 wineries tend to the vines here with a blend of Chardonnay, Riesling and Gewurztraminer plus varieties like La Crescent, Edelweiss and Chambourcin and Noiret.

Winegrowing on the Niagara Escarpment of Ontario is made possible by the lake’s influence. The same limestone cliffs that form Niagara Falls extend westward into Ontario. During the cold winters, the escarpment holds the warmer lake air in place. The narrow band between the lakeshore and cliffs is wine country. The Beamsville Bench, Twenty Mile Bench, Niagara-on-the-Lake and other growing areas are thus protected from killing temperatures. Riesling, Chardonnay, Gamay, Pinot Noir and more are all successful here thanks to Lake Ontario’s influence.

Niagara Escarpment and Vineyard

Michigan is among the most glaciated of states. Most of the land surface is covered glacial “drift” — the mélange of gravel, sand, clay and detritus that settled on the surface when the massive glaciers melted. The most noted Michigan wines come from the Leelanau Peninsula AVA and the Old Mission Peninsula AVA. These two parallel AVAs extend into Lake Michigan from Traverse City and benefit from the moderation of the lake. Vineyards are supplanting former cherry and apple orchards as the reputation of the wines grows. Fine sparkling wines from the L. Mawby winery in the Leelanau Peninsula AVA are justifiably accorded high praise. There are many fine bottlings of Riesling, Pinot Blanc, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Noir and more that come from these AVAs. There is justified excitement about the quality potential of northern Michigan wines.

Old Mission Peninsula — Michigan

The Lake Michigan Shore and Fennville AVAs in the southwest part of the state are best known for red wines. Located 200+ miles south of Traverse City, the area is slightly warmer. Many excellent examples of Cabernet Franc, Syrah and Blaufränkisch are produced here. The quality of the best wines can compete with similar-priced wines from anywhere.

There is a burgeoning winescape on the western shore of Lake Michigan as well. The Glacial Hills and Door Peninsula of Wisconsin are home to dozens of wineries. Cold hardy varieties like La Crescent, Frontenac and Brianna are planted here with a few sites planted to Riesling and Chardonnay. There are even a few wineries on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, truly the edge of viable viticulture in this part of the world.

Glaciers have carved more than just the Great Lakes. The Finger Lakes of New York have resulted from the same glacial sculpting, as has Lake Chelan in Washington and Lake Okanagan that straddles the US — Canadian border. Take some time to visit a winery or two the next time you are in Great Lakes country and see what’s new.