Iowa, although famous for agriculture, is not known for wine production. Amidst the profusion of corn and soybean fields, however, there is a burgeoning wine industry. With nearly one hundred wineries now operating in the Hawkeye State, it’s clear that wines overall are improving. While a few wineries are experimenting with vitis vinifera grapes, most are working with cold-hardy varieties bred for the harsh winters experienced in the state.

Location of the Loess Hills District AVA

There is a new AVA in the U.S. The Loess Hills District AVA was approved by the TTB in April of 2016. While the approval did not make headlines in the wine press, the district is an interesting example of a site identified most importantly by its distinctive soil type. There are only a few wineries in the district to date and the styles of wine are quite divergent, as one might expect from such a nascent region. Time will tell how the wine style develops, but there are promising signs even now of quality wine potential.

The Loess Hills District AVA is a long, narrow region of loess-based hills along the western banks of the Missouri and Big Sioux Rivers in western Iowa and northwestern Missouri. The AVA stretches from near the Iowa-South Dakota border south to Craig, Missouri, and east to Exira, Iowa, encompassing the regions where the depth of the loess is greater than 20 feet. From Omaha, Nebraska on the west side of the Missouri River, you can see the ridge of loess as you look eastward across the river.

Looking East toward the Loess Hills

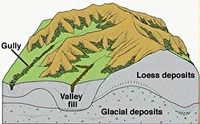

The primary distinguishing feature of the Loess Hills District AVA is the deep loess. Loess is a loose, crumbly soil comprised of quartz, feldspar, mica, and other materials. The topography of the AVA is characterized by rolling-to-steep hills. Wind and water erosion has sculpted the ridge crests into irregular shapes called “peaks and saddles,” and streams have carved steep-sided valleys into the soft loess. When dry, loess particles form stable surfaces. Wet loess, however, is very susceptible to collapse because of a lack of clay particles which normally bond wet soils together. In places where the soil has become heavily saturated, the loess can give way, lending a staircase-like terraced appearance locally called cat steps. Outside of the Loess Hills District, the local topography is generally flatter and lower.

Cross-Section of the Loess Hills

Loess is common around the world and is often noted for its agricultural productivity. The Grüner Veltliners of Austria’s Wagram, the luscious Tokaji wines of Hungary, several great Rieslings from Germany’s Nahe and Pfalz are all noted for loess soils as is Walla Walla in Washington State. Iowa’s Loess Hills are unusual because the layers of loess are extraordinarily thick, as much as 300 feet in some places. The thickness of the loess layers and the intricately carved terrain of the Loess Hills make them a rare geologic feature.

Loess is an aeolian (wind-deposited) soil. Over the last two million years, there have been several advances of massive continental glaciers over North America. The ice was thousands of feet thick and transformed the landscape that we see today. The last glacial advance ended some 20,000 years ago – very recently by geologic time standards. The glaciers advanced as far as the center of today’s Iowa, grinding underlying rock into a fine sediment called rock flour.

When temperatures rose and the glaciers receded, huge volumes of silt-laden meltwater poured down the Missouri River valley and were deposited on the floodplains of the river. As the river’s flow abated during the winter, the sediment would dry out and could be picked up by the strong westerly winds. This pattern was repeated over many cycles and the amount of sediment moved is impressive indeed. The heavier, coarser silt was deposited close to its Missouri River flood plain source and formed the sharp, high bluffs visible on the east bank of the river. This distinctive topographic feature is the Loess Hills.

The loess soils have advantages for winegrowers. The deep loess enables roots to reach deeply into the soil and water will drain away from the roots quickly, which can be a problem in dry years. The soil within the Loess Hills typically has a high pH value, ranging from 6.9 to 7.3. The level seems especially hospitable to grape varieties like Noiret, St. Vincent, Vignoles, Traminette, La Crosse, Chambourcin and Norton. These are all grown successfully within the AVA.

The hilly, often steep, landscape affects viticulture within the district. Cold night air drains off the slopes and away from the vineyards, reducing the risk of frost. The steep slopes also shed excess water more quickly, reducing the risk of fungal diseases and rot but increasing the susceptibility to erosion. Overall the Loess Hills District is measurably warmer than its neighbors, giving a growing season a week or two longer than most surrounding areas.

Terracing for Erosion Control in the Loess Hills

There are currently only eight wineries in the Loess Hills District AVA. Most all are planting varieties like those listed above as well as St. Croix, La Crescent, Edelweiss, Brianna and more. While these are unfamiliar names to most wine drinkers, they are becoming better known as wineries throughout the central U.S. vinify them. Many wineries focus on sweeter styles that are popular in the tasting room and balance the sometimes-high acidities of these new varieties. The Bodega Victoriana Winery in Glenwood has successfully emphasized their dry red wines. The path for future producers is open to a wide range of wine styles.

Vineyard in the Loess Hills AVA

In a geologic sense, the Loess Hills are a temporary, if rare and unusual, landform. They are very youthful and highly susceptible to erosion. Perhaps they have only another 100,000 years before they erode away completely. When originally deposited, they were most likely characterized by rounded hilltops and dune-like topography. In the last 20,000 years they have been transformed into their current shape with steep-sided gullies, sharp ridges and slumping hillsides. That’s plenty of time to enjoy the fruits of this distinctive terroir. Travel the Loess Hills Wine Route if you travel to the area. It’s a most interesting journey.