Readers might reasonably ask why I am writing about wines not available in the U.S. market from one the last places on earth you’d expect to find fine wine–Morocco, a Muslim country where alcohol is forbidden. Why? Because it is a fantastic story about problem solving, a learning curve, and perhaps a little bit of following your heart.

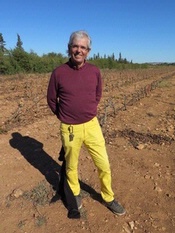

Although Charles Melia founded Val d’Argan in Morocco in 1995, the story starts much earlier. Charles, who is, by his own description, “French and Catholic,” is, at heart, Moroccan. His great grandfather had  been part of the French contingent in Algeria in the mid-19th century and afterwards the family remained in North Africa, even after Morocco gained its independence from France in 1956. His father, mother and uncle were all born in Morocco. Charles spent most of his childhood in Morocco, which explains why he could instruct his Moroccan vineyard workers, in what sounded like perfect Arabic, precisely how he wanted them to prune the vines.

been part of the French contingent in Algeria in the mid-19th century and afterwards the family remained in North Africa, even after Morocco gained its independence from France in 1956. His father, mother and uncle were all born in Morocco. Charles spent most of his childhood in Morocco, which explains why he could instruct his Moroccan vineyard workers, in what sounded like perfect Arabic, precisely how he wanted them to prune the vines.

In 1942, Charles’ grandfather purchased Château de la Font de Loup, now a well-regarded estate in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, sight unseen on the recommendation of a friend. (Given that this was wartime France, it would be two years after the purchase before he actually saw the property first-hand, according to Charles.) In the family tradition, Charles ran Château de la Font de Loup starting in 1977, but after a decade and a half, he had other ideas. He wanted to, as he described it, “branch out from the family estate.” He spent what he estimates as three years looking at vineyards in Chile, Argentina and finally Morocco.

Searching in Morocco took time. He explains, “I knew what I didn’t want to do.” He didn’t want to go to an “established” Moroccan region like Meknès, Rabat, or the Atlas Mountains (though some might question his use of the word “established” in this context.). He wanted to find a new place, so he started looking for potential areas in the south of Morocco for vineyards, but found the soil far too sandy near Agadir. Gradually moving north and staying near the cooling influences of the Atlantic Ocean, he found his current locale, just east of the Atlantic seaside resort of Essaouira, where he spotted vineyards that produced table grapes.

To his pleasant surprise, he found limestone, which is a perfect foundation for the roots of vines, under the 1.5-foot of topsoil. The soil  itself contained what turned out to be a literal mountain of stones, fragments of the limestone bedrock. Though different in origins, the stone-filled vineyards at Val d’Argan are reminiscent of those in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Jérôme Dourdin, a recently transplanted Frenchman who, along with his wife, has a delightful small hotel, Dar Diamar, 15 minutes away from Val d’Argan, lamented, “The thing that grows best in the garden is rocks.” The stone is so prevalent that much of the local construction–houses and walls–are built from the ubiquitous warmly colored pale-brown stone.

itself contained what turned out to be a literal mountain of stones, fragments of the limestone bedrock. Though different in origins, the stone-filled vineyards at Val d’Argan are reminiscent of those in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Jérôme Dourdin, a recently transplanted Frenchman who, along with his wife, has a delightful small hotel, Dar Diamar, 15 minutes away from Val d’Argan, lamented, “The thing that grows best in the garden is rocks.” The stone is so prevalent that much of the local construction–houses and walls–are built from the ubiquitous warmly colored pale-brown stone.

Melia purchased a 12.5-acre olive grove, uprooted most of the trees, removed enough stone for the eventual construction of his house, and planted 13 different Rhône varieties–shades of Châteauneuf-du-Pape–in what he described as a viticultural laboratory. Even Melia concedes his first wines were “not so good.”

Echoing Melia, Cornelia Hendry, the co-owner of the charming hotel, Villa Maroc in Essaouira, commented that the initial wines from Val d’Argan were heavy and not very drinkable. Now, however, they are on the hotel’s wine list and are “very popular.”

Melia explains the transition, “I started with European ideas, and now I know I needed Moroccan ideas.” In the vineyards, which have been farmed organically since their inception, Melia has added cover crops and has engaged in what he refers to as “progressive replanting,” expanding to his current 125-acres. He has planted more Syrah, Mourvèdre, and Marselan, a genetic cross of Grenache and Cabernet Sauvignon, Viognier and Roussanne, because he finds that those are the varieties that do best here. He is especially pleased with Marselan. When replanting, he trained the vines to be very low to the ground and closer together, not to compete with each other to limit growth, but rather so the leaves from one vine shade other vines to prevent the grapes from being sunburnt. Pruning to keep the grape-containing canes close to the ground keeps the grapes cooler. These techniques are critical because of the heat. This year, on the 23rd of June, the temperature reached 124º F, according to Melia. As a result, he lost his entire crop of Mourvèdre to sunburn and desiccation. He refers to his method of planting as the “Moroccan gobelet.” Melia notes that even with irrigation–he has three wells–his yields are small, averaging only 25 hectoliters/hectare.

The winery, built over three years from 1995 to 1998, is traditionally low-tech French and very efficient. Small crates of hand-harvested grapes arrive on the second floor of the winery, where Melia has placed a small de-stemmer. The grapes are destemmed and then drop directly–no use of pumps–into a press for the whites or cement fermentation tanks for the reds. He proudly reports that the time between picking the grapes and pressing them is about 30 minutes. He uses only natural yeast and relies on very little aging in oak barrels–those he uses are large and older–preferring to highlight the wine’s fruitiness.

Melia admits that in the beginning his wines were “too big. I was trying to make them like I did in Châteauneuf-du-Pape.” He points out that the most important change in his red winemaking since he started twenty years ago has been limiting extraction, which has made the wines lighter, fruitier and more elegant.

He credits the addition of an expensive system of circulating cold water to keep fermentation temperature constant and low. His harvest occurs in July or August when sugar levels are appropriate to achieve wines with between 13 and 14 percent alcohol. However, at that point, the tannins are still unripe and firm. Gentle extraction at low temperature helps him to minimize the harshness of the tannins in the finished wine.

The most surprising element of Melia’s Moroccan wines–both red and white–is their refinement. I was expecting robust wines with high alcohols, great density and power, characteristic of wines made in hot climates. After all, that’s frequently the character of California wine. But in California the temperature might climb “only” to the lows 100º F for a few days–not 120º F. In warm areas when tannin ripeness lags behind sugar ripeness, winemakers are faced with the decision of whether to wait for the tannins to ripen, knowing that the higher sugar levels will translate to higher alcohol wines, or to harvest when the tannins are still green leading to wines with firmness in their youth. Melia seems to have achieved an extraordinary balance in his wines given the climate by getting them to the winery quickly, through gentle handing of the grapes in the winery, and via low temperature extraction.

Even youthful barrel samples of wines from the 2017 vintage were refined. The Syrah, lighter with less spice compared to those from the Rhône, had finesse. Marselan from barrel showed more tannin and structure, but without a trace of heaviness. It had surprisingly good acidity and balance. A sample of Viognier-Grenache blend from the tank was perfumed, clean, fresh and filled with nuances of stone fruit. It was hard to believe it came from a desert-like locale.

Bottled wines–he has four levels–were equally impressive. At every level, the hallmark was freshness, vivacity and finesse. The flavors of a 2011 Val d’Argan Reserve red, a blend of Grenache, Syrah and Mourvèdre, had transformed from firm fruitiness apparent in the 2014 of the same wine to a suave succulence, while the 2014 Orian, a blend of Mourvèdre and Marselan and Val d’Argan’s flagship, was denser with an even a more refined texture. The whites were refreshing, clean and crisp and a perfect complement to the region’s seafood. All weighed in at 14 percent or less stated alcohol.

Since Val d’Argan’s wines are not (yet) imported into the U.S., it is impossible to know what prices they might fetch here. In Moroccan restaurants, Orian, Val d’Argan’s top tier red or white, at about $50, was always the most or second most expensive Moroccan wine on the list, while their excellent Perle Noir or Perle Blanche, which represents their second from the bottom tier, was about $30, pretty much in line with many other Moroccan wines.

Until 2003, Melia supervised production at both Val d’Argan and Château de la Font de Loup. It was a quick flight from Marrakech to Marseille and he could oversee the critical harvest period at both estates since they were separated by two months. But since 2003, he turned over the winemaking at Château de la Font de Loup to his daughter and son-in-law, while devoting all his energy to his Morocco estate. The wines at Val d’Argan show it.

Email me your thoughts about Moroccan wines—or anything else—at [email protected] and follow me on Twitter @MichaelApstein

January 3, 2018