Wine lovers are fond of associating famous wines with the soils from which they are drawn. One of the first facts the Burgundy neophyte learns about the region is that Pinot Noir does not perform well in the decomposed granite soils of the Beaujolais Mountains. Thus, it is learned that Gamay is the preferred grape there because it makes the better wine. From this starting point, many assume that it is the mineral composition of the soil that yields the striking character of fine cru Beaujolais. However, it is difficult to argue for granite having a taste, nor is it logical to associate a particular wine flavor profile with a rock type. Plus, many wines beyond Beaujolais are successfully grown on granitic soils in many parts of the world, with diverse varieties like Chenin Blanc, Riesling, Syrah, Zinfandel and others providing stellar examples of granite-spawned wines.

A recent study of bedrock influence on wine in South Africa by Shange & Conradie is a five-year analysis of Sauvignon Blanc and Cabernet Sauvignon grapes grown on soils from granite and shale bedrocks. This detailed analysis reveals no consistent and clear relationship between wine quality and the bedrock soil sources. The study showed that the growing conditions of the vintage had a greater impact on wine quality.  In wet years, the granite soils, with their better drainage, yielded superior wines. In dry years, the shale based soils, with their superior water retention, yielded wines reckoned as superior.

In wet years, the granite soils, with their better drainage, yielded superior wines. In dry years, the shale based soils, with their superior water retention, yielded wines reckoned as superior.

What is so special about granite then? Geology students learn about it in basic classes. It is a coarsely crystalline igneous rock that is formed under immense heat and pressure conditions far below the earth’s surface. A molten rock mass cools slowly and crystals of various minerals are knit together in a tight mass. The actual composition can vary based on the chemical mix of this molten soup. It all becomes quite complex, and there are many rocks classified as “granitoid” in character. True granite is one of these, but it also includes rocks like quartz monzonite, syenite, granodiorite and quartz diorite. This just clutters the understanding of true granite, but since commercial “granite” — used for countertops, tile and bathroom stall dividers — encompasses all these rock types and more, it’s useful to understand that true granite is just one of many granitoid rocks.

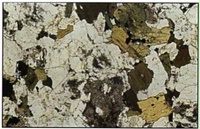

Getting back to the essence of granite, it is composed largely of quartz and feldspar, with minor components of mica, hornblende and other minerals. We most often associate granite with its pink hue. That is  because the feldspar in granite contains an abundance of sodium and exhibits a pink color that stands out next to the clear to white quartz crystals and the black micas. Studies of how igneous rocks form show that, as the molten mass cools, micas crystallize first, followed by feldspars and finally by quartz. Further studies indicate that these minerals decompose on the earth’s surface at a rate inverse to their formation sequence. This is logical when you consider that the black mica crystals, which form at the highest temperature, are further away from their formation conditions when at the low temperature of the earth’s surface and thus less stable. This renders the unstable minerals most susceptible to chemical weathering and breakdown. Quartz crystals are the last to form in the melt and are thus more stable and enduring.

because the feldspar in granite contains an abundance of sodium and exhibits a pink color that stands out next to the clear to white quartz crystals and the black micas. Studies of how igneous rocks form show that, as the molten mass cools, micas crystallize first, followed by feldspars and finally by quartz. Further studies indicate that these minerals decompose on the earth’s surface at a rate inverse to their formation sequence. This is logical when you consider that the black mica crystals, which form at the highest temperature, are further away from their formation conditions when at the low temperature of the earth’s surface and thus less stable. This renders the unstable minerals most susceptible to chemical weathering and breakdown. Quartz crystals are the last to form in the melt and are thus more stable and enduring.

So, as granite is exposed, the micas weather first, then the feldspars, leaving the quartz crystals in loose aggregation. The micas and feldspars, however, change chemically in the weathering process into clay minerals. These are small diameter particles that winnow their way down into the soil profile over time, much as the finer fraction of broken flakes in a box of cereal settles to the bottom of the box, leaving the larger flakes visible on top. The result of all this weathering is the desirable soil characteristics that vintners love. The upper soil horizon is largely composed of loose quartz crystals that drain well, and the subsoil contains lenses of clay minerals weathered from the feldspars and micas that give vine roots access to water throughout the growing season.

into the soil profile over time, much as the finer fraction of broken flakes in a box of cereal settles to the bottom of the box, leaving the larger flakes visible on top. The result of all this weathering is the desirable soil characteristics that vintners love. The upper soil horizon is largely composed of loose quartz crystals that drain well, and the subsoil contains lenses of clay minerals weathered from the feldspars and micas that give vine roots access to water throughout the growing season.

Where in the world do we find fine wines drawn from granitic soils? We are aware of Beaujolais, even though the majority of Beaujolais vineyards lie south of the famous Crus and planted on limestone rather  than granite. Perhaps the next most famous French region for granite soils is the great hill of Hermitage, where powerful Syrahs dominate production. Also in the northern Rhône, the Condrieu AOP is comprised largely of granite based soils and provides the world with luxurious and aromatic Viognier wines. Elsewhere in France, in the Pays Nantais, the ancient granites of the village of Clisson provide the base for the famous Muscadets from that site. The Alsace Grands Crus of Schlossberg, Brand, and Sommerberg are known for Rieslings drawn from granitic terroirs as well.

than granite. Perhaps the next most famous French region for granite soils is the great hill of Hermitage, where powerful Syrahs dominate production. Also in the northern Rhône, the Condrieu AOP is comprised largely of granite based soils and provides the world with luxurious and aromatic Viognier wines. Elsewhere in France, in the Pays Nantais, the ancient granites of the village of Clisson provide the base for the famous Muscadets from that site. The Alsace Grands Crus of Schlossberg, Brand, and Sommerberg are known for Rieslings drawn from granitic terroirs as well.

From other points in the Old World, we find granite based soils on the island of Corsica that yield wines from Nielluccio (Sangiovese) and  Sciaccarello (Mammolo). The north shore of Sardinia and the vineyards of the Vermentino di Gallura DOCG are on granite soils. In Spain, the Albariños of Rías Baixas are often drawn from granitic vineyards, as are the Vinhos Verdes from across the Minho River in Portugal. The Dão DOC in Portugal is noted for its granitic soils, where the Touriga Nacional, among other grapes, yields expressive red wines.

Sciaccarello (Mammolo). The north shore of Sardinia and the vineyards of the Vermentino di Gallura DOCG are on granite soils. In Spain, the Albariños of Rías Baixas are often drawn from granitic vineyards, as are the Vinhos Verdes from across the Minho River in Portugal. The Dão DOC in Portugal is noted for its granitic soils, where the Touriga Nacional, among other grapes, yields expressive red wines.

In the New World, South African vineyards are often planted on the widespread decomposed granite soils of the Cape. Paarl Mountain is a splendid example of rounded landform that weathering granite often takes. Both Paarl and Stellenbosch have extensive decomposed granite soils. We find high quality Chenin Blanc as well as Sauvignon Blanc and Bordeaux varieties planted here with success.

In Australia, the Granite Belt of Queensland is noted for its eponymous soils and provides a home for Chardonnay, Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc, Tempranillo and Bordeaux red varieties. Additionally, the vineyards of Tumbarumba in New South Wales offer Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs from granitic terrain. In Victoria, the Shiraz vines of southern Heathcote grow in decomposed granite as well.

Wineries in the Sierra Foothills of California have long touted the superiority of their Zinfandels from decomposed granite soils. Amador and El Dorado counties offer many other grape varieties — Barbera, Petite Sirah, Muscat, Mourvèdre and many more– from their granite-based terroirs. Other areas, like Paso Robles and Chalone have granite-base soils as part of their vineyard mix.

That’s just a quick Tour de Granite of the world’s vineyards. With such a wide range of fine winegrowing areas included, it’s easy to see why vintners like granite-based soils. There is much more granite exposed at the earth’s surface, however, with no vines in sight. All the other factors, from degree of slope, aspect to the sun, latitude, local weather patterns, and so on must coalesce for granite soils to work their special magic for the vines.