At the most granular level, we know the soil composition around even a single vine will be slightly different (as will the microscopic living creatures within its rhizosphere) than the vine growing next to it. And even when we speak of distinctive characteristics of a single vineyard, that single vineyard may vary in size from a few rows of vines to dozens of acres.

So how much does “single vineyard” printed on a wine label really mean? A winegrower may try to get her hands around that problem by subdividing a vineyard into multiple plots, each harvested separately. While the resulting blended wine still  is technically a single vineyard, the winemaker has consciously weeded out the lesser elements of that terroir and thus watered down is true, complete nature.

is technically a single vineyard, the winemaker has consciously weeded out the lesser elements of that terroir and thus watered down is true, complete nature.

Now multiply this complication when trying to establish a new, or understanding an existing, regional appellation – all those AVAs, DOCs, DOPs, IGPs and Pagos where geology often means less than geography and economic politics.

The Napa Valley AVA, for example, is based strictly on geography – its boundaries are essentially those of Napa County with little common terroir. To correct this, the AVA over the years has approved 16 subdivisions – what it calls “nested appellations” – to account for its diversity of soils and microclimates. So how much terroir and taste commonality are we talking about when we say, “Napa Valley Cab?”

And what if your primary AVA is a whole state? And if you are looking to establish a sub-appellation there, how much of its final configuration will be based on terroir, on geography and the politics of who should be left out – or in?

This was the challenge that Rachel Martin knew she was facing when she underwent  the (should we say Sisyphean or Quixotic?) task of trying to create an appellation for the region of northern Virginia where her family’s Boxwood winery is located. No matter where the lines were drawn, someone would find a very reasonable objection to it – the geology or topography decided upon would leave something out or bring something in that seemed unreasonable.

the (should we say Sisyphean or Quixotic?) task of trying to create an appellation for the region of northern Virginia where her family’s Boxwood winery is located. No matter where the lines were drawn, someone would find a very reasonable objection to it – the geology or topography decided upon would leave something out or bring something in that seemed unreasonable.

It should be noted that Martin’s task is one frequently faced by those in developing (or rediscovered) wine regions, especially in the Eastern U.S., as winegrowers and wine drinkers try to pin down a wine’s grapes provenance. Charting a new AVA means seeking a commonality among all wines in the newly designated region while distinguishing those grapes and its wines from those in nearby areas. (These AVA considerations came up repeatedly during interviews I conducted while researching recent articles about Virginia wines and winemakers for World of Fine Wine, Drinks Business and the American Wine Society Journal.)

Virginia is increasingly being recognized for its superior wines, so both producer and buyer are trying to narrow the focus of its wines to the state’s individual geographic parts. Currently, eight AVAs have been approved, and the two getting the most praise for quality are Martin’s Middleburg AVA in the northern part of Virginia and the Monticello AVA encircles Charlottesville farther south along the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge.

“AVAs are personally not that important to me, but from an industry standpoint, it is paramount to long-term survival,” says noted winemaker Jeff White of Glen Manor Vineyards near Front Royal. “We want people to come here for wine quality, not just for tourists who say, ‘Oh, and you also make wine.’”

Nate Walsh, whose Walsh Family Wine is within the Middleburg AVA, says, “We need to have more producers to focus on AVAs, but some [AVAs] are too big. We need to have sub-AVAs and stricter guidelines. Monticello AVA is ahead of us in some ways. You see it on more of their labels.”

But Lee Campbell, a partner in Common Wealth Crush Co. in the Shenandoah worries about putting the bottling line before the fermenters. “It’s a little early for us to start emphasizing AVAs,” she says, instead preferring Virginia in general remain the focus of identification.

Martin, who has now ventured to California where she co-founded Oceano Wines in San Luis Obispo, undertook the AVA task in 2006. “There are a couple of reasons I decided to do that,” she recently told me. “All our wines at Boxwood were estate-grown, but I couldn’t put that on the label with just a state AVA. Second, we wanted to educate consumers about the state’s different parts, its different regions.”

It became a time-consuming process. “It took a couple of years to refine [the complex AVA definition] and submit to the TTB [Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau],” she says, “which I did in 2008.” In 2010 there ensued several periods of public comments, and the approval was finally given on Oct. 15, 2012, seven years after Martin first began the process.

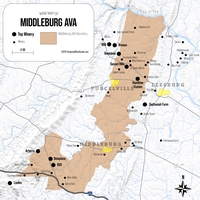

As finally defined, the Middleburg AVA begins at the Potomac River and runs south through the towns of Purcellville and Middleburg, then barely crosses I-66 near  Delaplane. It encompasses almost 130,000 acres, although less than 250 of them in vines. There are several highly regarded wineries within the Middleburg AVA, among them RdV Vineyards, Delaplane Cellars, Boxwood, Walsh Family Vineyards, Naked Mountain Vineyard and Doukenie Winery. It’s proximity to Washington, D.C., 50 miles to the east, adds to its popularity.

Delaplane. It encompasses almost 130,000 acres, although less than 250 of them in vines. There are several highly regarded wineries within the Middleburg AVA, among them RdV Vineyards, Delaplane Cellars, Boxwood, Walsh Family Vineyards, Naked Mountain Vineyard and Doukenie Winery. It’s proximity to Washington, D.C., 50 miles to the east, adds to its popularity.

“It’s a soil-based AVA,” Martin says, “with elevation and degree days as other factors.”

As with every appellation, the question comes down as to which geographic identification goes on the front label. In Europe, that is strictly regulated. And so it is Napa Valley, which convinced the state legislature to pass a law dictating that a Napa Valley sub-AVA or nested appellation cannot be printed bigger or more prominently on its label than is “Napa Valley.” If you prefer using your Stags Leap appellation over Napa Valley, tough luck.

My own take on appellations in general and the desire to link defining taste and typicity to terroir is that it’s always a rough measure at best. To be truthful, most of us would anticipate more what a wine will taste like by its grape variety or its blend of varieties than from where those grapes were grown. Even those who are expert at identifying what unknown wine is in their glass will usually start with the variety, and then try to work their way back.

As an interesting side note to the Middleburg example, and one which readers who know more about the Middleburg AVA than I do will be happy to see that I’ve finally mentioned, is that the official name is the “Middleburg Virginia” AVA, and not just “Middleburg.”

“The TTB said there were too many Middleburgs in the United States,” Martin says, “and that we would have to add the state.”

I’ll wait a few years before asking how, say, a Middleburg Cabernet Sauvignon might taste different than one from Monticello, Shenandoah Valley, or the Eastern Shore.