– J. Harlan Bretz

The distinctive landforms of eastern Washington inspired that statement from J. Harlan Bretz, the geologist who famously championed the now widely-accepted theory that cataclysmic glacial era floods created the landforms. The flood scoured landscape and the flood-associated impacts have also created a unique spot for wine in the US.

The Palouse is a geographic region in eastern Washington and Oregon plus western Idaho that is among the more distinct geomorphic sites in North America. A journey  to the Palouse will offer thousands of square miles of pillowy, rolling hills punctuated by steep valleys where rivers have incised the high plateau. It is now fertile agricultural land with extensive wheat fields dominating the landscape. The Walla Walla AVA lies within the Palouse and was established in 1984. There are now 120+ wineries in the region. Walla Walla wines are now well-known among wine lovers. What is less recognized is the unique sequence and scale of geologic events that has formed this enchanting landscape.

to the Palouse will offer thousands of square miles of pillowy, rolling hills punctuated by steep valleys where rivers have incised the high plateau. It is now fertile agricultural land with extensive wheat fields dominating the landscape. The Walla Walla AVA lies within the Palouse and was established in 1984. There are now 120+ wineries in the region. Walla Walla wines are now well-known among wine lovers. What is less recognized is the unique sequence and scale of geologic events that has formed this enchanting landscape.

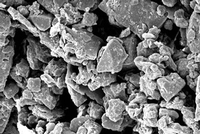

The Palouse is covered with a layer of loess, ranging from a thin cap to beds that are hundreds of feet thick. Loess (Löß in its native German) means “loose” – a reference to the poorly compacted nature of the soil. Loess is, in geologic terms, a recent deposit of windblown silt. Silt particles are very small – 0.002 to 0.063 millimeters in diameter. That’s 100 times smaller than your average beach sand grain size, so it’s easy to see how silt particles can be transported by strong winds.

Loess soils are found throughout the world, comprising ten percent or more of the earth’s soil surface. These widely distributed soils are of interest to winegrowers because they have proven to provide a beneficial habitat for grapevines. We find references to loess and wine most commonly in Austria, Germany and Hungary as well as eastern Washington state.

It is important to note that these are wind-borne deposits. Even in microscopic form, the silt particles collide in the turbulent winds and develop or maintain an angular form in the transportation process. Particles that are entirely transported by water often become rounded. Thus, when deposited, the airborne silt can become a cohesive soil while the water borne particles cannot. Think of trying to stack marbles as opposed to cubes and you can imagine the same forces at work in loess deposition.

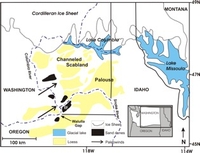

How then did so much loess come to be deposited in the Palouse? Where did this volume of dust come from? The answer lies in the repeated continental glaciations over the past two million years. At the glacial maximums, sheets of ice thousands of feet thick moved southward across Canada, pulverizing rocks into “rock flour” along the way, ending in northern Washington state. There were at least four major glacial advances and retreats during that time and many smaller movements as well. During glacial retreats, vast volumes of glacial meltwaters built up behind ice dams on what is now the Clark Fork River of northern Idaho. Glacial Lake Missoula formed behind the ice dam. The lake covered some three thousand square miles and contained up to 500 cubic miles of water – half the volume of Lake Michigan.

During warming periods, the ice dam would collapse. Then, nearly unimaginable volumes of sediment-laden flood water would cascade across the landscape of eastern Washington toward the modern Columbia River Valley, creating distinctive geomorphic features J. Harlan Bretz called the channeled scablands. These glacial outburst floods occurred not just once or twice, but perhaps 40 times or more. It is difficult to discern because new floods tend to destroy the evidence of previous inundations.

There is a constriction called the Wallula Gap on the Columbia River and the massive floodwaters would back up and pond in the Walla Walla Valley as well as the Pasco and Yakima Valleys. These temporary lakes likely lasted only for days but left behind thick deposits of sediment incorporating various gravel, sand, silt and clay components. As the sediments dried out, the strong prevailing southwesterly winds began to move them. The winds first moved the rounded sand grains which would bounce off the silt particles in a process called saltation – effectively sandblasting the silts and allowing them to become airborne in what must have been impressive dust clouds.

Eureka Flats, now a low-lying plain on the east bank of the Columbia River, is aligned in the direction of the wind. It was covered repeatedly with Missoula Flood sediments and was a perfect source for dust. Helped along by strong winds funneling through the Wallula Gap, the flood sediments were lifted and transported east. Ultimately, the winds would abate or precipitation would occur and the airborne silt would settle across the landscape as loess. Like a snowscape, the silt would settle in thick drifts in protected areas and blanket the land, covering all with a soft, undulating appearance.

The composition of the Palouse loess varies with time of deposition and distance from the source, but is generally about 40% quartz, with the balance mostly feldspars, micas and carbonates plus rock fragments and trace amounts of many other minerals. Once deposited, the feldspars and micas can weather to clay minerals, which provide the crucial water-retention properties of loess soils.

The combination of easy workability and an optimal balance of drainage and water retention make loess soils desirable not only for vines, but for many other crops as well. Loess is stable when it remains dry, but subject to severe erosion if it gets too wet. Terracing and other erosion control methods are often required to hold the loess in place.

Vineyards on the Palouse Loess in Walla Walla

Loess in some form is the primary soil type in most of the Walla Walla AVA. It can vary in thickness, but it blankets the hillsides throughout the appellation. The substrate can vary between flood deposits and basalt bedrock. Many of the pioneering wineries in Walla Walla get their grapes from vines grown in loess. Leonetti, Woodward Canyon, l’Ecole No.41, Pepper Bridge, Seven Hills among many others are all wineries whose vineyards benefit from the Palouse loess. Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah are the most widely-planted grapes, but there are many new varieties being planted as well. We will see a range of different and interesting wines because of this experimentation. In the past two decades, dozens of new wineries have been established in Walla Walla and there are more startups every year. The AVA is truly a work in progress, and we can look forward to more fine wines.

The glacial outburst floods had a profound impact on the landscape of southeast Washington and beyond. The Willamette Valley of Oregon was also inundated by backed-up floodwaters that dropped sediments in the valley. The massive floods provided the silt supply that blanketed thousands of square miles of land downwind from the source. Rich soils have formed in the deep loess, allowing not only the vast agricultural development for grain but also the basis for one of America’s distinctive winegrowing regions. If you travel to the area for wine education, make sure to visit and appreciate the truly unique surroundings and the forces which created this marvelous region.